The Wage Effects of Experience in Self-Employment

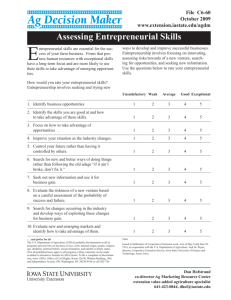

advertisement