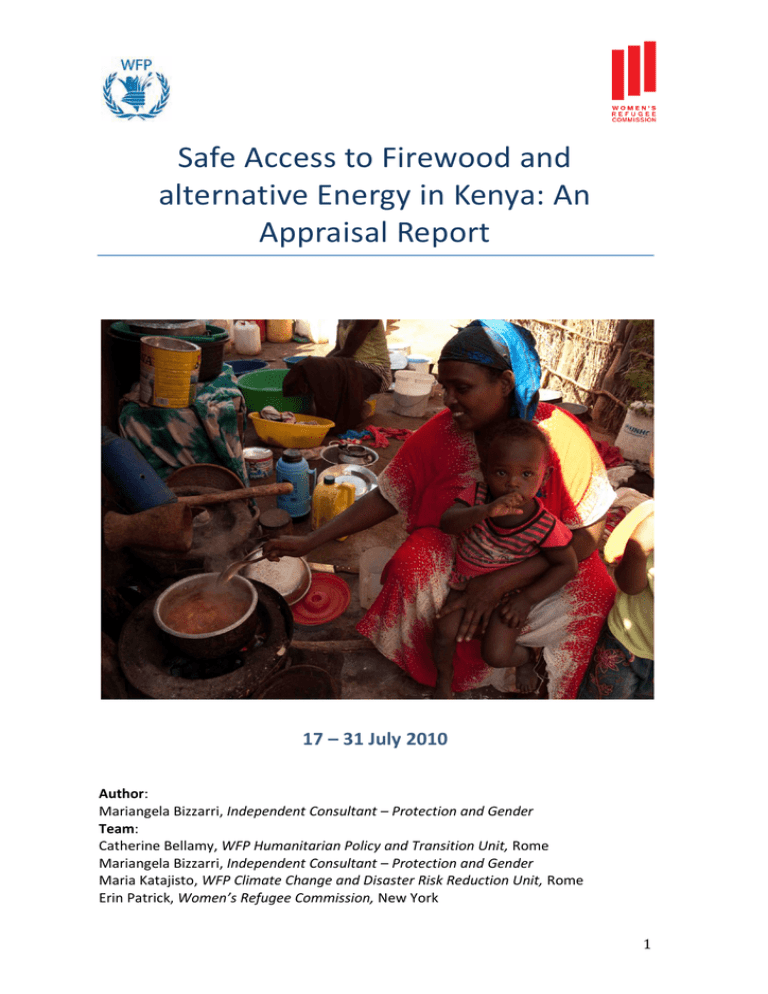

An Appraisal Report - Safe Access to Fuel and Energy

advertisement