Pole Pole: Hastening Justice at UNICTR

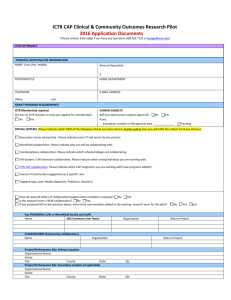

advertisement