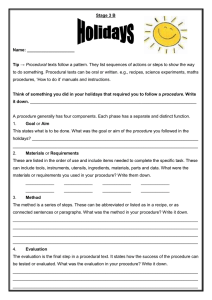

Special Issue on Procedural Fairness

advertisement