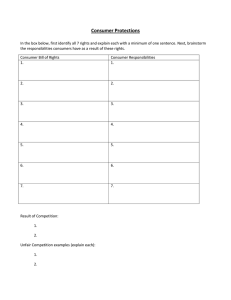

Chapter Nine Contracts and Consumer Law

advertisement