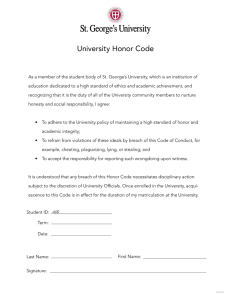

Honor Code Review

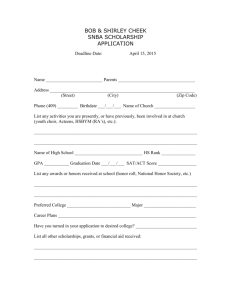

advertisement