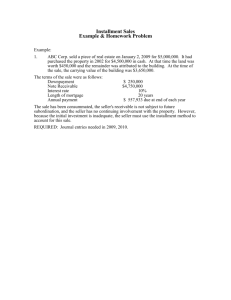

Income Measurement and Profitability Analysis

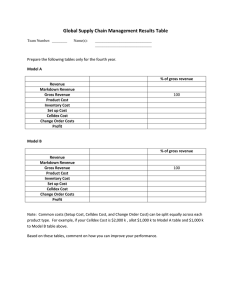

advertisement