revealed performances: worldwide rankings of economists

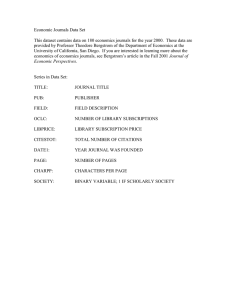

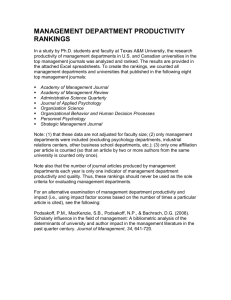

advertisement