A Comparison of Columnar-to-Equiaxed Transition Prediction

advertisement

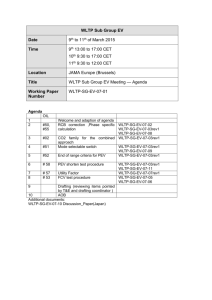

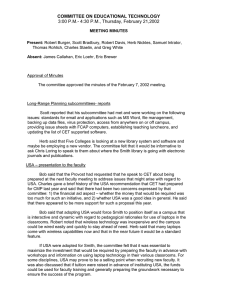

A Comparison of Columnar-to-Equiaxed Transition Prediction Methods Using Simulation of the Growing Columnar Front S. MCFADDEN, D.J. BROWNE, and CH.-A. GANDIN In this article, the columnar-to-equiaxed transition (CET) in directionally solidified castings is investigated. Three CET prediction methods from the literature that use a simulation of the growing columnar front are compared to the experimental results, for a range of Al-Si alloys: Al-3 wt pct Si, Al-7 wt pct Si, and Al-11 wt pct Si. The three CET prediction methods are the constrained-to-unconstrained criterion, the critical cooling rate criterion, and the equiaxed index criterion. These methods are termed indirect methods, because no information is required for modeling the equiaxed nucleation and growth; only the columnar solidification is modeled. A two-dimensional (2-D) front-tracking model of columnar growth is used to compare each criterion applied to each alloy. The constrained-to-unconstrained criterion and a peak equiaxed index criterion agree well with each other and some agreement is found with the experimental findings. For the critical cooling rate criterion, a minimum value for the cooling rate (between 0.07 and 0.11 K/s) is found to occur close to the CET position. However, this range of values differs from those cited in the literature (0.15 to 0.16 K/s), leading to a considerable difference in the prediction of the CET positions. A reason for this discrepancy is suggested, based on the fundamental differences in the modeling approaches. DOI: 10.1007/s11661-008-9708-x Ó The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society and ASM International 2009 I. INTRODUCTION THE columnar-to-equiaxed transition (CET) is a phenomenon that is sometimes revealed by macroetching a section of a cast component. The columnar region consists of elongated grains with a preferred growth direction. The equiaxed region consists of many grains with low aspect ratios and random orientations. A CET is formed at the shared boundaries at which the two zones meet. Sometimes the transition is more gradual and spread over a mixed columnar-equiaxed zone. There is a technical advantage to knowing if and when a CET may occur in a cast component. For example, directionally solidified turbine blades are manufactured to promote a columnar zone (thus avoiding the CET), because a columnar structure along the length of the turbine blade improves the creep resistance at high temperatures. In other applications, small equiaxed grains can give a higher yield strength and an improved liquid feeding in castings. Recently, Ares et al.[1] demonstrated how CET affects the resistance of a Zn-Al alloy to corrosion. They measured the charge-transfer resistance for a group of Zn-Al alloys. It was shown that, in some cases, the equiaxed zone could have better S. MCFADDEN, Postdoctoral Researcher, and D.J. BROWNE, Senior Lecturer, are with the School of Electrical, Electronic, and Mechanical Engineering, University College Dublin, Dublin 4, Ireland. Contact e-mail: shaun.mcfadden@ucd.ie CH.-A. GANDIN, Senior Research Scientist, is with the CEMEF - UMR CNRS 7635, MINES ParisTech, Sophia Antipolis 06904, France. Manuscript submitted June 11, 2008. Article published online January 15, 2009 662—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 corrosion resistance than the columnar zone. Thus, much attention has been given to the phenomenon of CET. Spittle[2] gave a recent review of CET experimental and modeling work. Columnar dendrites, which form the columnar grains, typically nucleate at a mold or chill surface. Initially, during a competitive growth phase, the dendrites grow under a moderately high temperature gradient. The preferred crystallographic direction for columnar dendrites is for h100i dendrite arms to grow in the direction opposite to the heat flow. In contrast, the equiaxed dendrites prefer to grow in the bulk undercooled liquid, where the temperature gradients are much lower. Equiaxed dendrites nucleate with seemingly no preferred crystallographic orientation. Equiaxed grains can originate in different ways. Hutt and StJohn[3] gave a summary of the origins of equiaxed grains. Typically, equiaxed grains nucleate at the site of an existing particle in the melt. Alternatively, equiaxed dendrites can originate from fragments of the columnar dendrites, and the detached arms grow to become equiaxed grains (Jackson et al.[4]). Regardless of the origin of the dendrites, it is clear that the condition of the bulk liquid determines whether a columnar zone or an equiaxed zone prevails. The growth restriction for a binary alloy is quantified in the literature as a factor Q,[5] where it is shown that Q helps establish the relationship between the undercooling at the columnar dendrite tip and the growth rate. Specifically, the undercooling at the columnar dendrite tip and the temperature profile within the liquid determine the extent of the undercooled liquid region ahead of the columnar front. The temperature gradients in the undercooled liquid play an important role in the METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A macrostructure formation. This relationship between the growth rate and the temperature gradient in forming the CET is succinctly described in the CET diagram of Hunt.[6] Hunt’s diagram is a plot of the dendrite tip growth velocity vs the temperature gradient. From the diagram, one can see the combinations of growth velocity and temperature gradient that give a fully columnar, fully equiaxed, or mixed columnar-equiaxed structure. Modifications to Hunt’s original CET diagram are available. Gäumann et al.[7] developed a CET diagram based on a more sophisticated dendrite growth law, while Martorano et al.[8] have included the effects of solutal interactions between dendrites, to give a modified CET diagram with solutal blocking effects. Quested and Greer[5] append the Hunt diagram with contours of equal grain size in the equiaxed region of the diagram. The CET is also predicted by simulating the growth of the solidification macrostructure. As discussed in Reference 9, two approaches are possible, namely, direct and indirect methods. In the direct approach, the nucleation and growth of both a columnar and an equiaxed mushy zone are simulated. Models exist that simulate the CET at various length scales, for example, at the macro scale[10–16] and at the micro scale.[17–19] In the indirect approach, only the evolution of the columnar mushy zone is modeled, that is, the nucleation and growth of the equiaxed zone is omitted. In this case, the condition ahead of the columnar front is analyzed with respect to the possibility of an equiaxed zone forming there. This article focuses on indirect CET prediction techniques. A two-dimensional (2-D) front-tracking model of columnar growth[14,15] is used and comparisons between various indirect CET prediction methods are assessed. An advantage of using this type of indirect approach is the reduced simulation run times: the final results are gathered expeditiously. Furthermore, reliable detailed information about the nucleation criteria of equiaxed grains, which is usually difficult to obtain, is not required for the simulation runs. II. INDIRECT CET PREDICTION In this article, we discuss three published indirect CET criteria: the constrained-to-unconstrained columnar growth criterion, the critical cooling rate criterion, and the equiaxed index. A. Constrained-to-Unconstrained Criterion Gandin[20] developed a one-dimensional front-tracking model of columnar growth using Landau transforms to explicitly track the dendritic tip and eutectic interface positions. The growth of the dendrite tip was determined by the undercooling at the tip relative to the liquidus temperature; the growth of the eutectic interface was determined by the undercooling at the interface relative to the eutectic temperature. Between the columnar dendrite tip and the eutectic interface, the mushy METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A zone followed a truncated Scheil solidification path.[21,22] The enthalpy was calculated for the system based on both the heat transfer by conduction and the latent heat released during solidification. The thermophysical properties varied with the temperature and the solid fraction. Gandin compared the results of the model to the results from experiments on directionally solidified alloys.[23] Agreement was found between the model and the experimental cooling curves for the majority of the solidification times. Any differences in the cooling curves were attributed to the omission of the equiaxed solidification from the model. The location of the CET was measured from the experimental results. The model was able to provide the growth rate of the columnar front and the temperature gradient in the liquid for every position of the front. It was observed that, when the columnar front reached the position of the observed CET, the columnar growth rate had reached a local maximum and the temperature gradient in the liquid had switched to become slightly negative. Thus, the growth regime at the dendrite tips changed from constrained to unconstrained (a positiveto-negative temperature gradient). Gandin proposed that the CET coincided with the point at which the local maximum dendrite growth rate and the constrained-to-unconstrained transition occur. It was suggested that these growth conditions could favor a fragmentation mechanism as the source of the equiaxed grains, as was previously observed.[4] Ares et al.[24,25] estimated the temperature gradients at the CET position for a series of directionally solidified binary alloys. They reported temperature gradients close to zero at the CET position, with some gradients being slightly negative. B. Critical Cooling Rate Criterion Siqueira et al.[26,27] conducted directional solidification experiments on Al-Cu and Sn-Pb alloys, to analyze the CET. Their furnace was instrumented to establish the heat-transfer coefficient at the chill surface. A model of the columnar solidification using the heat-conduction energy equation and the Scheil equation was developed, to analyze the cooling conditions achieved in the furnace. It is important to point out that the model of Siqueira et al. assumed that solidification begins at the liquidus temperature. No distinction was made between columnar and equiaxed zones in this heat-flow analysis. Siqueira et al. used their model to study the thermal conditions at the position of the liquidus isotherm. They plotted the isotherm velocity and temperature gradient for each position of the liquidus isotherm. Furthermore, by multiplying the isotherm velocity and gradient for each position, the cooling rate at the instantaneous position of the liquidus isotherm was plotted. It is important to clarify that the calculated cooling rate was the cooling rate at the position of the isotherm and not the cooling rate of the isotherm, which is, obviously, zero. When comparing the cooling rates to the measured CET positions, the authors concluded that the CET VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009—663 occurrences coincided with a critical cooling rate. After additional investigation, it was also concluded that the critical cooling rate remained constant for each alloy regardless of the thermal parameters (initial temperature, heat-transfer coefficient, etc.). For Al-Cu systems, the critical cooling rate was measured as 0.2 K/s;[26] for Sn-Pb alloys, it was 0.014 K/s.[27] The critical cooling rates given were specific to the alloy system but independent of composition. Later, Peres et al.[28] performed similar experiments with Al-Si alloys and showed that, for this alloy system, the critical cooling rate varied. The critical cooling rates for CET in their Al-Si ingot varied from 0.15 to 0.2 K/s, with variations in silicon content ranging from 3 to 9 wt pct. Most recently, the critical cooling rates for Al-Ni and Al-Sn systems were found to be invariant and were 0.3 and 0.16 K/s, respectively.[29] C. Equiaxed Index Browne[30] developed an indirect method for CET prediction based on a columnar-front-tracking model. As already mentioned, the columnar-front-tracking model distinguishes between dendritic columnar mush and undercooled liquid. In this CET prediction method, the bulk undercooled liquid ahead of the columnar front was analyzed. To demonstrate, consider a square computational grid made up of orthogonal control volumes, with dimensions Dx and Dy. The number of rows in the grid is nrows and the number of columns is ncols. An equiaxed index, I(t), was calculated at each time, t, in the simulation; it was defined as IðtÞ ¼ nrows cols X nX the alloy composition and heat-transfer coefficient; the peak equiaxed index increased with an increasing solute content and a decreasing heat-transfer coefficient. Qualitatively, it was proposed that this trend was supported by foundry experience, because it was shown elsewhere that an increased solute content[31] and a lower heattransfer coefficient[32] increased the extent of the equiaxed zone. Hence, it was proposed that the peak equiaxed index be used as an indicator to give the relative likelihood of an equiaxed zone forming in a casting-mold cavity of fixed dimensions. The results of Browne[30] were recently directly compared to those of a front-tracking model of combined columnar and equiaxed growth.[33] It was shown that the simulated equiaxed zone increased in qualitative agreement with the peak equiaxed index. In addition to the peak equiaxed index, the undercooling dwell time, which is the accumulated time during which a control volume remains undercooled, was suggested as a good indicator for the location of the equiaxed zone.[34] Preliminary investigations[35] showed that the index could increase when the effects of the natural thermal convection were included in the simulation. No previous direct quantitative experimental validation of the equiaxed index was performed; rather, its predictions were shown[30] to be in qualitative agreement with a range of experimental studies from the literature. This article aims to test, for the first time, the proposed equiaxed index criterion against the experimental results. III. Ub ði; jÞDxDyjt¼const ½1 i¼1 j¼1 where Ub(i,j) was the level of the undercooling in the control volume with coordinates (i,j) and 8 if Tði; jÞ>TL <0 Ub ði; jÞ ¼ TL Tði; jÞ if Tði; jÞ TL and dði; jÞ<0:5 : 0 if Tði; jÞ TL and dði; jÞ 0:5 ½2 where T(i,j) is the node-center temperature at a control volume, TL the liquidus temperature, and d(i,j) the volumetric fraction of any control volume captured by the columnar mushy zone. The bulk undercooling was calculated, as described, only in undercooled liquid control volumes; elsewhere, Ub(i,j) = 0. The index I(t) can be interpreted as the discrete integral of the bulkliquid undercooling across the domain. The equiaxed index plotted as a function of time (where it started at zero for a superheated liquid) increased as the extent of the undercooled liquid zone increased, reached a peak value, and diminished to zero as the bulk liquid was consumed by mush. Browne investigated three compositions of an Al-Cu alloy cast in similar molds, but with each alloy simulated three times with different heat-transfer coefficients at the walls. The peak value of the equiaxed index changed depending on 664—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 EXPERIMENTAL CASES Gandin’s experimental data[23] for a series of directionally solidified Al-Si alloys are used in this analysis. The experimental procedure consisted of melting the alloys in a crucible and pouring the liquid into the mold that is maintained in a furnace to achieve a uniform temperature. Removing the apparatus from the furnace and applying a water-cooled chill to the bottom surface of the cylindrical mold allowed solidification to proceed in the upward direction. The final ingot size was 7 cm in diameter and approximately 17 cm in height. The Al-Si alloy system is not prone to solutal-driven natural convection, because both aluminum and silicon have similar densities. Cooling from below ensures that the liquid is also stable with regard to thermally derived density gradients in the liquid. It is usually assumed that the effect of the natural convection in the liquid can be neglected in this case. The three alloys studied were Al-3 wt pct Si, Al-7 wt pct Si, and Al-11 wt pct Si. The apparatus had seven thermocouples along the central axis, which were uniformly spaced by 2 cm. The CET positions measured for Al-3 wt pct Si, Al-7 wt pct Si, and Al-11 wt pct Si alloys were 12.0, 11.8, and 10.9 cm, respectively, measured from the bottom of the ingot. A tolerance of ±1 mm was quoted with each CET position. Additional data from the experiments, namely, additional cooling curves and averaged equiaxed radii, are available in Martorano et al.[8] METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A IV. COLUMNAR-FRONT-TRACKING MODEL A 2-D model of the furnace was developed using columnar front tracking. Additional details about the front-tracking algorithm are available in Reference 15; additional details about front tracking with an implementation of the Scheil algorithm are available in Reference 14. Equivalence with other models from the literature is to be emphasized,[8,10–12,20,21] because all these models use a tracking method to follow the position of the columnar growth front and the undercooling at the position of the front. The thermophysical properties for the alloys changed as a function of temperature and phase fraction, according to the following equations: Vm Vm KS ðTÞ ½3 KL ðTÞ þ gs KCV ðT; gs Þ ¼ 1 gs VCV VCV Fig. 1—Furnace schematic, with a flowchart for the inverse-heattransfer algorithm. and CCV ðT; gs Þ ¼ Vm Vm 1 gs CS ðTÞ ½4 CL ðTÞ þ gs VCV VCV where KCV (T,gs) is the thermal conductivity of the control volume as a function of the temperature, T, and the solid fraction, gs; KL(T) and KS(T) are the thermal conductivities of the liquid and solid, respectively; and Vm is the mushy or captured volume in a control volume of size VCV. The specific heat at a control volume is CCV(T,gs); CL(T) and CS(T) are the specific heats of the liquid and solid, respectively. The properties for the liquid and solid are approximated with quadratic polynomials, which are based on best fits for the available data, as in PðTÞ ¼ a2 T 2 þ a1 T þ a0 ½5 where P(T) is the property of interest (either the specific heat or the conductivity) and a2, a1, and a0 are the coefficients. The temperature is given in degrees Celsius. The following dendrite growth law governs the columnar front growth rate: vt ¼ ADT n ½6 where A is a growth constant, DT the undercooling at the tip (given by TL – T), and n a growth exponent. The vertical mold walls are assumed adiabatic. During the experiments, there was a gap between the liquid-free surface and the top of the mold. Similar to Gandin[20] and Martorano et al.,[8] the heat flux across the free surface was estimated at some value up to a cutoff time; after this time, the heat flux was assumed to be zero. The heat flux at the chill surface was an unknown and could not be estimated as simply. An inverse-heattransfer method was developed based on a modified proportional integral derivative (PID) control algorithm. Figure 1 shows a schematic for this inverseheat-transfer scheme. The model is allowed to run and the simulated temperature at a position of 2 cm from the chill surface is returned to the controller; this is the calculated temperature. The measured temperature from METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A the thermocouple at the 2-cm position is provided to the controller; this is the desired temperature. The error in the model, e, is the difference between the calculated and desired temperatures at the 2-cm position. This error value is then used to change the heat flux at the chill surface. The heat flux at the chill, q, is given by the following expression written in the Laplace domain, s, instead of the time domain: KI KD s ½7 qðsÞ ¼ eðsÞ KP þ þ 1 þ ss s where KP, KI, and KD are the coefficient of the PID controller, and s the break period of a first-order lag that helps to filter any noise on the differential channel. The PID terms KP, KI, and KD were selected by tuning the system response with the Ziegler–Nichols method.[36] The value of s was selected as s ¼ 0:1 KP KD ½8 Thus, Eq. [7] describes a negative feedback control system. The controller algorithm gives a dynamic response, that is, it changes with time, so that no iteration is required during the explicit time-stepping algorithm. The algorithm is robust; it can allow for the phase change and changes in thermophysical properties without having to make any adjustments to the algorithm parameters. The temperature of the sample at the chill face is simulated; thus, the model simulates the heterogeneous nucleation of the columnar front from the chill face. Reference 16 explains an approach to obtaining the boundary conditions for a microgravity experiment on solidification that is similar to that used in a model of a PID controller V. ALLOY PROPERTIES Table I gives the properties used in the simulations for the three alloys. The data from the phase diagram, the VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009—665 Table I. Alloy Al-3 Wt Pct Si Al-7 Wt Pct Si Al-11 Wt Pct Si 640 0.12 577 660 1 1.7 9 103 2.7 969 618 0.13 577 660 1 2.9 9 104 2.7 1064 590 0.14 577 660 1 1.0 9 104 2.7 1159 Liquidus temperature, TL (°C) Segregation coefficient, k Eutectic temperature, TE (°C) Pure aluminium melting temperature, TM (°C) Columnar nucleation undercooling, DTn (°C) Dendrite growth constant, A (cm/s °Cn) Dendrite growth exponent, n Latent heat, L (J/cm3) Specific-heat polynomial coefficients, q Cp (J/cm3 °C) a0 a1 a2 Liquid Solid Liquid Solid Liquid solid 2.775 3.040 9 104 0.0 2.422 9.598 9 104 0.0 3.06 3.247 9 104 0.0 2.349 9.720 9 104 0.0 3.083 2.330 9 104 0.0 2.422 9.598 9 104 0.0 Thermal conductivity polynomial coefficients, K (W/cm °C) a0 a1 a2 Alloy Properties Liquid Solid Liquid Solid Liquid Solid 0.5000 3.125 9 104 0.0 1.5581 2.284 9 103 3.84 9 106 0.4400 2.747 9 104 0.0 1.3581 2.284 9 103 3.84 9 106 0.3670 3.330 9 104 0.0 2.4125 1.050 9 103 1.262 9 107 dendritic growth kinetics, and the thermal conductivity are based on the values given by Gandin.[20] The latent heat data used here are based on measured latent heat data. It is well known that silicon, which has a latent heat value 4.6 times that of aluminum, has an important effect related to increasing the latent heat released from the alloy.[37,38] Djurdjevic et al.[38] investigated the increase in latent heat in commercial alloys, in terms of the chemistry and cooling rate. They showed that the cooling rate had a very small effect on the measured latent heat and that a silicon addition had the most significant effect. The specific-heat data for Al-7 wt pct Si and Al-11 wt pct Si are based on data given for commercial alloys in Reference 39. The commercial alloy Al-LM25 is quoted in Reference 39 with 7 wt pct silicon, 91.1 wt pct aluminum, and no more than 0.5 wt pct of other elements. Hence, the specific-heat values quoted for the liquid and solid LM25 are used here for Al-7 wt pct Si. Similarly the specific-heat data quoted for Al-LM13 are used because of the closeness of the alloy content to Al-11 wt pct Si. The LM13 constituents quoted in Reference 39 are 12 wt pct Si, 84.3 wt pct Al, and no more than 1.2 wt pct of other constituents. For Al-3 wt pct Si, we use the specific-heat data given by Gandin,[20] which are based on pure aluminum. This estimate is assumed reasonable because of the dilute nature of the 3 pct Si alloy. A comparison was made between the thermal conductivity data quoted for LM25 and LM13[39] and those quoted by Gandin[20] for Al-7 wt pct Si and Al-11 wt pct Si. These values for conductivity are in close agreement; thus, with confidence, the data given by Gandin are used. 666—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 VI. MODEL PARAMETERS The model uses an explicit time-stepping algorithm on a fixed orthogonal grid. Table II gives the size of the grid and the time-step. The initial temperatures for each simulation are listed here. As already explained, the heat flux at the bottom surface is estimated by using an adaptation of a PID controller algorithm. The PID controller gains are listed in Table II. These gains were established by tuning the Al-7 wt pct Si model to a Ziegler–Nichols criterion. The same gains work well for the Al-3 wt pct Si and Al-11 wt pct Si systems, thus demonstrating the robustness of the PID algorithm as an inverse-heat-transfer method. Table II. Simulation Parameters Simulation Run Domian size, D 9 H (cm) Grid size, Dx, Dy (cm) Time-step, Dt (s) Initial temperature, Tinit (°C) Controller proportional gain, KP Controller integral gain, KI Controller derivative gain, KD Heat flux from top, qloss (W/cm2) Cutoff time, tq (s) Al-3 Al-7 Al-11 Wt Pct Si Wt Pct Si Wt Pct Si 7 9 17 0.1 7.5 9 104 776.9 7 9 17 0.1 7.5 9 104 764.0 7 9 17 0.1 7.5 9 104 768.9 6.66 6.66 6.66 1.23 1.23 1.23 8.991 8.991 8.991 0.4 0.4 1.0 900 900 900 METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A Fig. 2—Cooling curves, isotherm and front positions, and temperature gradients for each alloy case: Al-3 wt pct Si, 7 wt pct Si, and 11 wt pct Si. Similar to previous work,[8,20] the heat flux, qloss, from the top surface is estimated to be constant up to a cutoff time, tq, after which time the heat flux is assumed to be zero. Table II gives the estimated heat loss and the cutoff times selected for our simulations. VII. RESULTS Figure 2 shows the first set of results in a 3 9 3 montage of images. The results for each alloy are arranged in rows: the first row shows the results for Al-3 wt pct Si; the center row, for Al-7 wt pct Si; and the last row, for Al-11 wt pct Si. Figure 2 shows the cooling curves in the column on the left, the liquidus isotherm and columnar front positions in the column in the center, and the simulated temperature gradients in the column on the right. Additionally, the graphs for the cooling curves in the column on the left in Figure 2 show the simulated cooling curves at the thermocouple positions and the experimentally measured cooling curves. Thus, a comparison can be made between the experiment and the model, for each alloy and for each simulation run. METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A The graphs for the liquidus isotherm and the columnar front position, in the center column in Figure 2, show the simulated liquidus isotherm position and the measured liquidus isotherm position. Thus, a comparison can again be made between the experiment and the model, for each case. The columnar front position was not measured during the experiment; therefore, only the simulated columnar front position may be shown. It should be noted that the columnar front nucleates on the chill surface and then travels away from it. It is the vertical dimension from the columnar front to the chill that is quoted. The temperature gradients, shown in the column on the right in Figure 2, give the simulated temperature gradients at the position of the columnar fronts. Two gradients are given, one in the liquid ahead of the columnar front and the other in the mush behind the columnar front. The temperature gradients are given as a function of the calculated position of the columnar front. The vertical dashed line in this set of graphs shows the measured CET position from the postmortem analysis. Overall, Figure 2 gives a summary of the simulated thermal conditions with comparisons to the measured thermal conditions from the experiment. VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009—667 Fig. 3—Simulated columnar growth rates, cooling rates, and equiaxed index for each alloy case: Al-3 wt pct Si, 7 wt pct Si, and 11 wt pct Si. Figure 3 shows the second, and final, set of results for the simulation cases in another 3 9 3 montage of images. Similar to Figure 2, the results for each alloy in Figure 3 are arranged in rows: the first row gives Al-3 wt pct Si; the center row, Al-7 wt pct Si; and the last row, Al-11 wt pct Si. The column on the left shows the growth rate of the columnar front as a function of the distance of the columnar front from the chill surface; the column in the center shows the instantaneous cooling rate at the position of the liquidus isotherm vs the distance of the isotherm from the chill; and the column on the right shows the equiaxed index for each position of the columnar front measured from the chill. The data in Figure 3 will be used to give a summary of the three CET prediction criteria. For reference, the measured CET positions are superimposed onto each graph as a vertical dashed line. VIII. DISCUSSION The column on the left in Figure 2 shows the cooling curves from the model compared to those measured on the experimental apparatus. The thermocouple positions are indicated on each cooling curve. From the first row, we see that agreement between the model and the experiment for Al-3 wt pct Si is quite good, especially 668—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 in the early stages of solidification. There is some small amount of deviation in the results toward the end of the experiment, at the 14-cm position. This location is well within the equiaxed zone; hence, this slight temperature deviation may be partly due to the absence of an equiaxed solidification model and, possibly, to the absence of a model of convection in the liquid. Also, we must consider that the 14-cm position is close to the free surface of the ingot, where a simple but crude approximation of the boundary condition was made. However, the general agreement is good. Similar agreement is found in the row in the center, for the cooling curves of Al-7 wt pct Si. Furthermore, direct comparisons can be made between this set of modeling results and those given by Gandin’s columnar solidification model,[20] offering some verification status to the present front-tracking model with the inverse-heat-transfer method. In the last row, we see more pronounced deviations between the model and the experiment for the Al-11 wt pct Si alloy. Deviations in this result may be due to the same reasons as cited earlier; however, general agreement is found during the majority of the cooling phase. The column in the center in Figure 2 shows the simulated position of the liquidus isotherm from the surface of the chill. The measured isotherm positions are compared to the predictions. Agreement between the model and the experiments is reasonably good; this METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A reinforces confidence in the ability of the model to predict the correct thermal conditions. In addition, Figure 2 (the column in the center) shows the simulated columnar front positions. It is clear that the columnar front lags behind the liquidus isotherm; the liquidus isotherm reaches the top of the ingot before the columnar front. The extent of the bulk undercooled liquid zone is simply the difference between the liquidus isotherm and the columnar front positions. It is clear that, during the first stage of solidification, this extent is small; it increases, however, until the liquidus isotherm reaches the top of the ingot, at which time the extent begins to decrease. It is this extent of the undercooled bulk liquid that plays an important role in the development of the equiaxed zone. The column on the right in Figure 2 shows the temperature gradients at the columnar front positions in the liquid ahead of the columnar front and in the mush behind. In the case of the Al-7 wt pct Si (in the center row), we can compare the experimental results to the modeling results reported in Reference 20. In this respect, the agreement between the present model and the results in Reference 20 is good. On the temperature gradient graphs, the vertical dashed line indicates the measured CET position. For the cases of Al-3 wt pct Si and Al-7 wt pct Si, the temperature gradient in the liquid becomes slightly negative at the point at which the CET occurred. Thus, in agreement with Gandin, a constrained-to-unconstrained transition takes place close to the CET position. However, applying the constrainedto-unconstrained criterion for the CET to the results for the Al-11 wt pct Si alloy shows that the CET should occur at approximately 12.5 cm from the chill surface. The measured CET was at 10.9 cm; thus, in this case, we see a 1.6-cm overestimate for the columnar length. Figure 3 gives a summary of the indirect CET prediction criteria vs the measured CET. The column on the left shows the simulation results for the columnar growth rate. As discussed by Gandin,[20] there is typically a local maximum in the growth rate close to the constrained-tounconstrained transition, which is also the predicted CET position. The column in the center gives the results for the critical cooling rate CET criterion of Siqueira et al.[26] The column on the right shows the results for the equiaxed index CET criteria of Browne.[30] For the Al-3 wt pct Si and the Al-7 wt pct Si cases, we see close agreement between the local maximum in the columnar front growth rate and the measured CET positions. When these results for columnar growth rates are considered in conjunction with the temperature gradient (Figure 2), we conclude that the constrainedto-unconstrained theory gives a good prediction for the CET position. For the case of Al-11 wt pct Si, the local maximum in the growth rate occurs at approximately 1.6 cm past the measured CET position; thus, as discussed earlier, the constrained-to-unconstrained criteria overestimate the CET position by 14.6 pct of the actual CET distance. The column in the center in Figure 3 summarizes the results for the critical cooling rate CET criteria. If we first consider the case of Al-3 wt pct Si (the first row), we see that the minimum cooling rate is approximately METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A 0.07 K/s and that it occurs approximately 1.5 cm before the measured CET position. By using the minimum critical cooling rate of Peres et al. (0.15 K/s), the predicted CET position would be 5 cm from the chill. The error associated with this prediction is approximately 7 cm. Similarly, for the Al-7 wt pct Si, the cooling rate reaches a minimum of approximately 0.11 K/s, just before the CET measured position. This minimum is below that quoted in the literature. To use the value from the literature, the columnar length for Al-7 wt pct Si is predicted to be approximately 6 cm, which is approximately 6 cm too short. For the case of Al-11 wt pct Si, we see a local minimum of approximately 0.1 K/s in the cooling rate at the measured CET position. Notably, if we used the critical cooling rate of 0.15 K/s (Peres et al.), we would have predicted a CET at approximately 1 cm from the chill; in other words, the prediction would give an almost fully equiaxed structure. Finally, the column on the right in Figure 3 summarizes the results for the equiaxed index CET criteria. For the Al-3 wt pct Si alloy, a peak value of 120 cm2 K is reached at the measured CET position. For the case of Al-7 wt pct Si, the equiaxed index peak value is 195 cm2 K. It is clear that, in this case, the CET occurred just prior to the point at which the equiaxed index reached the peak value. For the Al-11 wt pct Si alloy, a peak value of 180 cm2 K occurs at approximately 12.5 cm. Thus, the peak equiaxed index value, in the case of Al-11 wt pct Si, corresponds closely with the constrained-to-unconstrained transition; however, the estimate is approximately 1.6 cm too long for the columnar zone. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that the equiaxed index function gives the relative likelihood of a CET occurring. The chances of a CET occurring are reduced after the peak equiaxed index has occurred; therefore, the CET is most likely to occur before or at the peak equiaxed index. In this case of Al11 wt pct Si, the CET occurs just before the peak equiaxed index. It seems that the peak equiaxed index criterion is more robust and is less sensitive to errors in the thermal calculations than the critical cooling rate criterion, as demonstrated in the case of Al-11 wt pct Si. In Figure 3, the parameters are plotted as a function of the distance from the chill surface. This spatial plotting method was performed so that direct comparisons could be made with the measured position of the CET from the chill. All of the information in Figure 3 can also be plotted against time. No information about the temporal evolution of the CET was available for these experiments. Hence, it was impossible to draw a comparison between the simulated timing of a CET vs the measured times. As described in the literature, a realtime, in-situ observation of CET development requires 200-lm-thick samples and a powerful X-ray source.[40,41] However, comparisons between the simulated timing of events for each criterion were made. For Al-3 wt pct Si, the peak columnar growth rate occurred at 915 seconds of simulated time; the peak equiaxed index occurred at 930 seconds. These values are in reasonably good agreement with each other, considering that a 15-second difference corresponds to a 3-mm VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009—669 difference in the position of the columnar growth front, when it is growing at approximately 200 lm/s. In contrast, the critical cooling rate of 0.16 K/s occurred at the earlier time of 520 seconds; the minimum cooling rate achieved in the simulation occurred at 790 seconds. Similar trends were observed for the Al-7 wt pct Si and Al-11 wt pct Si alloys. For Al-7 wt pct Si, the peak columnar growth rate occurred at 950 seconds, the peak equiaxed index at 940 seconds, the critical cooling rate of 0.15 K/s at 570 seconds, and the minimum cooling rate at 775 seconds. For Al-11 wt pct Si, the peak columnar growth rate occurred at 1300 seconds, the peak equiaxed index at 1290 seconds, the critical cooling rate (0.15 to 0.2 K/s) at approximately 345 seconds, and the minimum cooling rate at 1110 seconds. Considering that the critical cooling rate criterion is based on the liquidus isotherm and not the columnar front position, it is no surprise that the critical cooling rate criterion predicts that the CET will occur earlier than the other criteria. The column in the center of figure 2 shows that the liquidus isotherm can be quite far ahead of the columnar front during the latter stages of solidification. IX. SUMMARY OF CET PREDICTION RESULTS Overall, using the columnar-front-tracking model, we see the following trends in the results at the CET position: (1) a local peak in the columnar velocity that also corresponds to a constrained-to-unconstrained transition, 2) a minimum value in the cooling rate at the position of the liquidus isotherm, and 3) a peak value in the equiaxed index. These trends seem to be in general agreement with previously published work.[20,26,30] However, the critical cooling rates calculated here seem lower than those from earlier work.[28] Our calculated critical cooling rates for CET are between 0.07 to 0.11 K/s, which, when compared with 0.15 and 0.16 K/s, is lower than expected. A reason for these discrepancies may come from the alternative modeling approaches. As mentioned, Peres et al.[28] uses a macroscopic model that is based on the modified specific-heat approach, which is similar to an enthalpy model. In their model, no distinction is made between columnar and equiaxed mush. A combined columnarequiaxed mushy zone is modeled with a Scheil approximation. In the columnar-front-tracking approaches of Gandin[20] and Browne,[30] a distinction is made for the columnar mushy zone. In the absence of an equiaxed solidification component to the model, these approaches distinguish between columnar mush and undercooled bulk liquid ahead of the columnar front. The modified specific-heat approach or enthalpy method used by Peres et al. does not allow for bulk undercooled liquid. (Refer to Banaszek et al.[42] for a detailed discussion of this distinction in the models.) Thus, a fundamental difference among the modeling approaches may account for the differences found in these experiments between the critical cooling rates required for CET and the critical cooling rates modeled here. However, because the CET is formed when the columnar front is blocked and because the columnar tips are undercooled, it seems 670—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 clear that the most successful CET criteria are based on models that allow for undercooling at the columnar dendrites. Most macroscopic models that solve the energy conservation with a unique solidification path do not distinguish the undercooled columnar dendrite tips within the mushy zone. X. CONCLUSIONS A columnar-front-tracking model combined with an inverse-heat-transfer method was applied to a series of directional solidification experiments on Al-Si alloys. The experiments in question were on Al-3 wt pct Si, Al-7 wt pct Si, and Al-11 wt pct Si binary alloys. Three CET criteria from the literature were tested to see how well the observed CET was predicted. The criteria involved were the constrained-to-unconstrained transition criterion, the critical cooling rate criterion, and the peak equiaxed index criterion. For Al-3 wt pct Si and Al-7 wt pct Si, the constrainedto-unconstrained criterion and the peak equiaxed index criterion predictions agreed well with the CET position. For the Al-11 wt pct Si alloy, the constrainedto-unconstrained and peak equiaxed index criterion overestimated the columnar length by 1.6 cm. This overestimation may be due to some discrepancies between the predicted and measured thermal conditions. A minimum cooling rate at the position of the isotherm was observed close to the CET position, for each alloy. However, the values of the critical cooling rate for a CET found here (0.07 to 0.11 K/s for Al-3 wt pct Si and Al-7 wt pct Si, respectively) differ considerably from those quoted in the literature (0.16 to 0.15 K/s for Al-3 wt pct Si and Al-7 wt pct Si, respectively[28]), leading to a large deviation in the predictions of the CET positions. It is proposed that the differences come from a fundamental difference in the modeling approaches used to obtain the values. The constrained-to-unconstrained criterion and the peak equiaxed index criterion may be used in conjunction with a columnar-front-tracking model to predict the CET position in noninoculated directional castings. Whether or not a CET occurs depends on the level of undercooling ahead of the columnar front. As suggested in Reference 34, the peak level of the bulk-liquid undercooling across the domain should also be considered, to determine whether a threshold value is reached. This threshold value could be the same as the mean value for the heterogeneous nucleation of the equiaxed dendrites. The critical cooling rate criteria should only be used in conjunction with a full enthalpy or a modified specific-heat model. A columnar solidification model, as used here, should not be used with the critical cooling rate criterion of Siqueira et al.[26] The indirect CET prediction criteria discussed here offer the significant advantage of giving reasonable CET predictions without the computational expense of modeling the development of an equiaxed zone. Thus, much computational run time can be saved when gleaning CET information for many casting cases. The equiaxed index method of Browne can be used for predicting the METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A CET in shape castings. It should be possible to define a lower bound on the equiaxed index required for the CET to occur in a particular casting. This level will be dependent upon the size and the geometry of the mold cavity, from casting to casting. It is yet to be established whether such criteria are valid for casting cases with rapid solidification or with the inoculation of the melt to enhance heterogeneous nucleation, or when strong liquid convection takes place. In the case of inoculated alloys, it is expected that nucleation of the equiaxed dendrites takes place before the temperature gradient in the liquid vanishes and well before the equiaxed index or columnar growth rate reaches its peak. The determination of a CET in this case requires information on the temperature gradient, the growth undercooling, and the equiaxed nucleation undercooling. A Hunt analysis should give good predictions of the CET in cases in which the inoculant details are known. Otherwise, direct modeling of the equiaxed structure is needed (as performed in other modeling approaches, for example, in References 14 and 43). In other work, the experiments discussed here are simulated with models that include details of an equiaxed mushy zone nucleating ahead of the columnar zone (References 8 and 14). Thus, these models predict the full extent of the combined mushy zone with both columnar mush and equiaxed mush. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors acknowledge the support of the European Space Agency through Columnar-to-Equiaxed Transition in Solidification Processing (CETSOL), a project of the Microgravity Application Promotions program. One of the authors (SMF) expresses his gratitude to Professor Emeritus Annraoi De Paor, for providing illuminating discussions on Control and Filter Theory. NOMENCLATURE A a0 a1 a2 CCV CL CS cp D d e gs H I i j K KCV dendrite growth coefficient polynomial coefficient polynomial coefficient polynomial coefficient specific heat for a control volume specific heat for liquid specific heat for solid specific-heat capacity diameter of ingot volume fraction of a control volume error solid fraction height of the ingot equiaxed index grid coordinate grid coordinate thermal conductivity thermal conductivity of a control volume METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A KD KI KL KP KS L n ncols nrows P Q q qloss s T TE Tinit TL TM t tq Ub VCV Vm vt DT DTn Dt Dx Dy q s derivative gain integral gain thermal conductivity of liquid proportional gain thermal conductivity of solid latent heat dendrite growth law exponent number of columns in a grid number of rows in a grid general polynomial value growth restriction heat flux at the chill surface heat flux at the free liquid surface Laplace coordinate temperature eutectic temperature initial temperature liquidus temperature melting temperature of solvent material time coordinate cutoff time for heat loss undercooled bulk liquid control volume size volume of mush in a control volume dendrite growth velocity undercooling nucleation undercooling time-step grid spacing grid spacing density first-order lag constant REFERENCES 1. A.E. Ares, L.M. Gassa, S.F. Gueijman, and C.E. Schvezov: J. Cryst. Growth, 2008, vol. 310, pp. 1355–61. 2. J.A. Spittle: Int. Mater. Rev., 2006, vol. 51, pp. 247–69. 3. J. Hutt and D. StJohn: Int. J. Cast Met. Res., 1998, vol. 11, pp. 13–22. 4. K. Jackson, J. Hunt, D. Uhlmann, and T. Seward: Trans. TMS-AIME, 1966, vol. 236, pp. 149–58. 5. T.E. Quested and A.L. Greer: Acta Mater., 2005, vol. 53, pp. 4643–53. 6. J.D. Hunt: Mater. Sci. Eng., 1984, vol. 65, pp. 75–83. 7. M. Gäumann, R. Trivedi, and W. Kurz: Mater. Sci. Eng., A, 1997, vols. A226–A228, pp. 763–69. 8. M.A. Martorano, C. Beckermann, and C.-A. Gandin: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2003, vol. 34A, pp. 1657–74. 9. S. McFadden, D.J. Browne, and J. Banaszek: Mater. Sci. Forum, 2006, vol. 508, pp. 325–30. 10. C.Y. Wang and C. Beckermann: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 1994, vol. 25A, pp. 1081–93. 11. C.-A. Gandin and M. Rappaz: Acta Metall. Mater., 1994, vol. 42, pp. 2233–46. 12. M. Wu and A. Ludwig: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2007, vol. 38A, pp. 1465–75. 13. G. Guillemot, C.-A Gandin, H. Combeau, and R. Heringer: Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2004, vol. 12, pp. 545–56. 14. S. McFadden and D.J. Browne: Appl. Math. Model., 2009, vol. 33, pp. 1397–416. 15. D.J. Browne and J.D. Hunt: Numer. Heat Transfer, B-Fund., 2004, vol. 45, pp. 395–419. 16. S. McFadden, L. Sturz, H. Jung, N. Mangelinck-Noël, H. Nguyen-Thi, G. Zimmermann, B. Billia, D.J. Browne, D. Voss, and D. Jarvis: J. Jpn. Soc. Micrograv. Appl., 2008, vol. 25, pp. 489–94. VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009—671 17. J. Li, J. Wang, and G. Yang: J. Cryst. Growth, 2007, vol. 309, pp. 65–69. 18. A. Badillo and C. Beckermann: Acta Mater., 2006, vol. 54, pp. 2015–26. 19. H.B. Dong and P.D. Lee: Acta Mater., 2005, vol. 53, pp. 659–68. 20. C.-A. Gandin: Acta Mater., 2000, vol. 48, pp. 2483–2501. 21. S.C. Flood and J.D. Hunt: J. Cryst. Growth, 1987, vol. 82, pp. 543–51. 22. S.C. Flood and J.D. Hunt: J. Cryst. Growth, 1987, vol. 82, pp. 552–60. 23. C.-A. Gandin: ISIJ Inter., 2000, vol. 40, pp. 971–79. 24. A.E. Ares, S.F. Gueijman, R. Caram, and C.E. Schvezov: J. Cryst. Growth, 2005, vol. 275, pp. 319–27. 25. A.E. Ares and C.E. Schvezov: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2007, vol. 38A, pp. 1485–99. 26. C.A. Siqueira, N. Cheung, and A. Garcia: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2002, vol. 33A, pp. 2107–18. 27. C.A. Siqueira, N. Cheung, and A. Garcia: J. Alloys Compd., 2003, vol. 351, pp. 126–34. 28. M.D. Peres, C.A. Siqueira, and A. Garcia: J. Alloys Compd., 2004, vol. 381, pp. 168–81. 29. M.V. Canté, K.S. Cruz, J.E. Spinelli, N. Cheung, and A. Garcia: Mater. Lett., 2007, vol. 61, pp. 2135–38. 30. D.J. Browne: ISIJ Int., 2005, vol. 45, pp. 37–44. 31. R.D. Doherty, P.D. Cooper, M.H. Bradbury, and F.J. Honey: Metall. Trans. A, 1977, vol. 8A, pp. 397–402. 32. I. Ziv and F. Weinberg: Metall. Trans. B, 1989, vol. 20B, pp. 731–34. 672—VOLUME 40A, MARCH 2009 33. S. McFadden and D.J. Browne: in Proc. 5th Decennial Int. Conf. Solidification Processing, H. Jones, ed., University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom, 2007, pp. 172–75. 34. S. McFadden, D.J. Browne, and J. Banaszek: in The John Campbell Symp, M. Tiryakioglu and P.N. Crepeau, eds., TMS, Warrendale, PA, 2005, pp. 365–74. 35. J. Banaszek, S. McFadden, D.J. Browne, L. Sturz, and G. Zimmermann: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2007, vol. 38A, pp. 1476– 84. 36. G.F. Franklin, J.D. Powell, and A. Emami-Naeini: Feedback Control of Dynamic Systems, 5th ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2006, pp. 95–106. 37. Y.Z. Sun, G. Cao, S.S. Yao, C. Yu, and W.Z. Zhang: J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ., 2001, vol. 35, pp. 473–76. 38. M.B. Djurdjevic, J.H. Sokolowski, W.T. Kierkus, and G. Byezynski: Mater. Sci. Forum, 2007, vols. 539–543, pp. 299–304. 39. K.C. Mills: Recommended Values of Thermophysical Properties for Selected Commercial Alloys, ASM INTERNATIONAL, Materials Park, OH, 2002, pp. 37–49. 40. G. Reinhart, N. Mangelinck-Noël, H. Nguyen Thi, T. Schenk, J. Gastaldi, B. Billia, P. Pino, J. Härtwig, and J. Baruchel: Mater. Sci. Eng., A, 2005, vols. 413–414, pp. 384–88. 41. R.H. Mathiesen, L. Arnberg, P. Bleuet, and A. Somogyi: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2006, vol. 37A, pp. 2515–25. 42. J. Banaszek, D.J. Browne, and P. Furmanski: Arch. Thermodyn., 2003, vol. 24, pp. 37–57. 43. G. Guillemot, C.-A. Gandin, and H. Combeau: ISIJ Int., 2006, vol. 46, pp. 880–95. METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS A