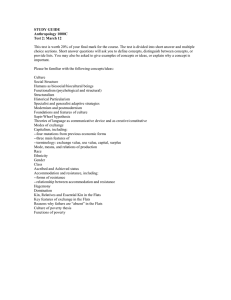

Owasco Flats Report - Central New York Regional Planning and

advertisement