Deskbook for Chief Judges of US District Courts

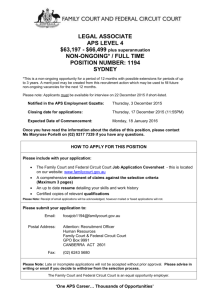

advertisement