Secondary education in Poland

advertisement

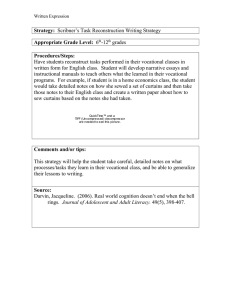

Jerzy Wiśniewski Secondary education in Poland 18 years of changes This short paper is going to present the transformation of the secondary and upper-secondary education in Poland during the period of the economic and social reforms introduced after 1989. Two segments of the secondary education: general and vocational, have followed two different tracks of reforms. The general secondary schools have benefited from the extended school autonomy, deregulation of the curricula, free market of textbooks and thus they have been able to attract more students. Most of their graduates aimed for the tertiary, academic education what was a good motivation to learn. While vocational schools, which were embedded in the economy of the socialist system and consisted an integral part of the state-owned enterprises, suffered from the changes within the economy (shrinking of the sectors of economy such as mining or heavy industry), the increasing unemployment and the lack of a plan of the necessary changes within this part of school education. The pace of the economic reforms was so quick that the vocational schools could not catch up with the appropriate (not to mention any anticipated) changes in curricula, teaching programmes and work organisation. As a result, graduates of that type of schools had difficulties in finding any job. That worsened the already not very good image of the vocational education, which had been considered as the worst option by both primary schools graduates and their parents. The vicious circle of the intake of low-achievers, outdated teaching programmes and instruction methods as well as poor outcomes (both in the terms of learning outcomes and their relevance to the labour market needs) remained unbroken due to lack of vision of the vocational education system reform. The departure point – school education in “real socialism” period The school education system existing in Poland before 1989 was characterised by extremely far-going centralisation. Strategies and policy for the development of education were designed by the authorities of the communist party. All other, even detailed, issues were decided by the Minister of National Education. The powers of the latter covered the issues concerning: • curricula, • textbooks and other teaching aids admitted for use in school, • rules for the functioning of all types of schools, • rules for recruitment of pupils to schools, • organisation of the school network, • classification of occupations and specialisations in which education in vocational schools was provided, • rules for awarding titles and diplomas attesting to vocational qualifications, • rules for organising and setting examinations. The school education system comprised (graph 1.): Eight-year primary schools (children aged 7 – 14) which task was to ensure all-round development of the pupil and prepare him/her to continue his/her education in a secondary school or in a basic vocational school training for employment. General lyceums (4-year, age 15-18) provided pupils with a possibility of completing general secondary education in four years. Having passed the final examination (maturity examination, matura), the graduates were entitled to apply for admission to higher education. Three-year basic vocational schools (in principle for students aged 15-17) trained skilled workers. The graduates were awarded a certificate attesting to qualifications in a given occupation. This certificate also served as the basis to apply for admission to supplementary technical schools where students could complete their secondary education and take the maturity examination. It was not the Ministry of National Education but individual sector ministries who were responsible for running schools which trained specialists for a given branch of the economy. Technical secondary schools (duration of 4 or 5 years; students aged 15-18, 19) awarded to their graduates the vocational title of technician attested by a secondary school leaving certificate. Upon completion of education in such schools, students could also take the maturity examination they needed to pass in order to be able to apply for admission to higher education. Post-secondary schools offered general lyceum graduates the possibility of acquiring vocational qualifications and the title of technician. pre-school education 0 I II III IV V VI VII VIII I II III IV V "zero" class primary school General Vocation. second. Second. Basic vocat. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Graph 1. The school education system 1989 During the seventies and the eighties of the last century more than 50% of the 15-18 year olds attended basic vocational schools, one third studied in secondary vocational schools and only less than 20% were in the secondary general education. Such proportion of the number of students in post-primary schools was the direct result of the policy of the communist party aimed at up keeping the dominant role of the workers’ class. Eventually Poland at the beginning of the nineties of the last century was among the European countries with the lowest participation rate in full secondary education and consequently also among those with the lowest rate of participation in higher education. This was not in line with the aspirations of young people as most of them wished to complete secondary general education and they planned to apply for higher education. There were two simple mechanisms used in combination to maintain such distribution of the primary school leavers: limited number of places available in general secondary education (numerus clausus) and the entrance examinations to such schools. The entrance examinations were organised by the regional educational authorities (kuratoria) and comprised of two written tests: Polish language and mathematics. Applicants were not allowed to retake the entrance examinations. At the age of 15 (completion of primary education) as still covered by compulsory education, young people could not wait a year to take again an examination to the chosen lyceum. Having failed the examination (or having obtained marks not good enough to be accepted to the chosen school), they were bound to continue education in a post-primary school, this most often being a basic vocational school. Only rarely was this a school which offered training for an attractive occupation, e.g. in the service sector; such schools were very popular and selected their pupils on the basis of a ranking of marks from the primary school at the beginning of the recruitment period. When the recruitment to lyceums was completed, no places were available in popular vocational schools. Underrating their abilities, many primary school leavers did not try to take examinations to a secondary school, fearing they might fail and be deprived of the possibility to choose their own further education route. One can hardly say how many of them were entirely wrong in the assessment of their own abilities and thus lost a chance to receive a better education. Beginning of changes 1989 The agreements concluded as a result of the Round Table negotiations in 1989 gave rise to tremendous changes in Poland and throughout the Central Europe. In September 1989, a new government was appointed with Tadeusz Mazowiecki as the first non-communist prime minister for more than 40 years. The Government soon launched radical economic reforms, introducing free-market economy rules. The reform brought numerous advantageous effects: the very high inflation, represented in three-digit rates, was curtailed; the Polish zloty was gradually made a convertible currency; a Stock Exchange was established; and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises was initiated. Changes in the economy curbed recession and led to the increasing economic growth rate in the following years. Simultaneously, these changes involved various social consequences. Some citizens decided to take their chance and established their own businesses. Many of them were successful; their living standard rose substantially and quickly. Those who were better educated and knew foreign languages found employment in foreign companies, emerging in an increasing number on the Polish market. This was another group that achieved success and benefited most from the economic transformations. These trends were, however, accompanied by the negative side-effects. Large state-owned enterprises were facing bankruptcy or drastically reducing employment. Unemployment appeared as a phenomenon unknown in the times of real socialism. This was a problem that neither citizens nor public institutions were prepared to cope with. In particular the Ministry of Education was unable to prepare proposals for any appropriate systemic measures. One among many factors curbing efforts to initiate reforms of education was the belief that it would require preparations and time to be implemented. Unlike the economy, education should not be treated with a shock therapy. This view in ‘normal’ times could hardly be disputed. However the educational authorities did not even try to elaborate a strategy of changing of vocational schools to introduce instruments which would give them a chance to cope with rapid changes in the economy and the labour market. There was also another obstacle to elaborate any strategy of the reform. It was the absence of an institution responsible for data-gathering, monitoring, analysing and strategic planning. Without such backup the Ministry was often ‘surprised’ by the side-effects brought by the developments in the economy, the labour market or within the educational sector itself.. The fundamental economic changes mentioned earlier significantly affected vocational education. Most enterprises that ran works-based schools refused to finance them any longer. These establishments had to be taken over by the educational authorities. Moreover, the enterprises that handed over their works-based schools would not guarantee employment to their graduates. This meant a break-up of the model existing in the times of real socialism: qualifications acquired within a narrow specialisation would no longer guarantee life-long employment in one state-owned enterprise. That important change in the paradigm of the vocational training was not accompanied by the introduction of any new forms of employers involvement in defining the scope of specialisations, teaching content, learning outcomes or qualifications. Also there was not enough effort made to develop the counselling and guidance system to help young people in making informed decisions on their educational and professional careers. However, the take-over of most vocational schools by the Ministry of National Education also brought about some desirable consequences as it initiated the process of transformations in this sector of school education. The most important was the graduate reduction of the number of students in basic vocational schools and the simultaneous increase of the number of students in full (giving the possibility to apply for higher education) secondary particularly general secondary schools. That responded to the social demand as the educational aspirations of young people had increased and many of them aimed at the tertiary education. They also realised that general education gave them better chance to find a job than narrow vocational training. Other activities undertaken by the Ministry of National Education in the area of vocational education included the following: • introducing changes in curricula for subjects related to economy promoting entrepreneurship; • introducing modern foreign languages into curricula (this decision being difficult to implement due to the shortage of teachers); • introducing an optional subject „Elements of Informatics”; • accepting for school usage 76 independently developed curricula and initiating the work on curricular documentation corresponding to the new classification of occupations. These changes were only to a slight extent meeting the needs of a reform of the vocational education, a sector which urgently required to be adjusted to the conditions and needs of the market economy. It was obvious that the basic vocational schools could not survive without significant changes. It was clear as well that the changes should influence the whole post-primary education. To develop such a comprehensive reform plan, the Ministry needed to decide on the extent and the moment (in the student's school career) of specialisation. There were two important factors which were taken into consideration. Firstly, how the wider access to secondary education would affect the quality. Secondly, how the changes in the structure and specialisation of schools would affect teachers employment. As said earlier, the discussions on different options were not facilitated by any research or analytical work providing for informed decisions. The practical answer to the first question was “stratification” of general secondary lycea. In many cases local authorities converted basic vocational schools that did not attract enough candidates into general education schools. Those schools accepted candidates who had lower results on entrance exams in comparison with the candidates applying to the schools with long tradition and the recognised prestige. Although the ‘average’ secondary school achievements might be lower (although there was no systematic monitoring to give evidence to proof that) ‘traditional’ lycea have maintained their quality measured by the success rate in applying for higher education. The opening of new lycea on the basis of basic vocational schools brought also a partial answer to the second problem: the employment of teachers. Partly, because in lycea there were jobs for teachers of general subjects. But what could have been offered to vocational teachers and trainers? One could say: further and continuing education and training might be the answer. Unfortunately there was not enough attention or support given to that segment of the education system. Tertiary Education The Ministry was concentrated on the increase in the participation rate in higher education. The number of students in higher education increased from 403.8 thousands in 1990/91 to 794.6 in 1995/96 and 1584.8 in 2000/01 with the corresponding net enrolment rates 9.8%, 17.2% and 30.6 %. Such significant increase in the participation was possible due to the changes in the system of financing of state universities (based on the number of students), the possibility of charging fees from students of evening and extramural courses in public higher education and the possibility to open private higher education schools. Consequently the access to higher education became easier and many secondary school graduates eagerly used that opportunity. They rightly believed that with the higher education diploma their chances for employment (even good employment) would be much higher. Also they postponed the moment of entering the labour market. The side effect was that only few secondary school graduates were interested in continuing education in post-secondary non-higher education. An important development in the area of education and training in the early 90-ties was the establishment of foreign language teacher training colleges. This new type of higher education institution in the Polish education system was set up primarily as a response to the need of promoting foreign language teaching in Polish schools. To make the readers fully aware of the importance of establishing teacher training colleges, it should be recalled that teachers were trained in various faculties of higher education institutions as specialists in a given branch of knowledge who, however, were not well prepared to work in school. Elementary education teachers could acquire necessary qualifications by taking two-year post-secondary courses in the so-called teacher training institutes. Teacher training colleges equipped the graduates with practical teaching competences and – thanks to intensive collaboration with foreign partners – prefect knowledge of languages. One can hardly overestimate the importance of the establishment of teacher training colleges. As a result of this decision, a new model of teacher training was introduced as an alternative to that based on master-degree courses in universities. It turned out soon that this was the beginning of a wider process of diversification of higher education. Large higher education institutions existing for many years began to set up teacher training colleges within their structures. Simultaneously, study programmes in many faculties were changed so as to enable the student to obtain the degree of bachelor or engineer after three years of study. Those who have obtained the first degree may study for the master degree. The same years saw the establishment of a large number of non-public higher education institutions. They were authorised by the Minister of National Education to provide only bachelor-degree courses as they were not prepared to offer master-degree courses in terms of staff and organisational requirements. Like teacher training colleges, non-public higher education institutions were often established in smaller towns where no universities existed. These initiatives attracted the support of local authorities which were right to see them as a chance for young people in their area to obtain higher education qualifications, and thus to boost the prestige of the town. Obviously, better educated inhabitants provide better conditions for investment in a given area (human capital), thus increasing chances for faster economic growth. This approach, shared by the Government and the Parliament, led to the adoption of the Act on Schools of Higher Vocational Education in June 1997. Unfortunately, as in many other countries, higher vocational schools aspire to became universities. Some regulations on employment in different professions did not help them in promoting the recognition of the bachelor (engineer) diploma. For example for teaching in a secondary school or to apply for the civil service the master degree is required. Now the higher vocational schools are not considered as an important alternative to the academic higher education. They are rather treated as the first stage of the tertiary education followed by the master degree courses. Technical lyceum Alongside with the structural changes in the secondary education there were efforts undertaken to change the curricula. The overall direction of the changes was the “generalisation” of vocational education. The idea was to increase the share of general education subjects in curricula and teaching programmes and to replace narrow, specialised vocational training by more general training covering branches of economy and trade. The result of that policy was the opening in 1993 of a new type of secondary vocational school - a four-year technical lyceum. The school provided general secondary education courses, giving students the possibility to obtain the maturity certificate and to complete general vocation oriented education covering a selected sector of the economy (specialised section). The following specialised sections were set up in the technical lyceum: economy and finance, electrical and power engineering, chemistry, environmental engineering, mechanical engineering and technology, agriculture and food, services and economy, administration and business support services, social sector and services, electronics, wood technology and forestry, steel industry and metallurgy, textile and clothing industry, communication and transport. When the technical lycea were introduced into the system the plan was that the next step would be the development of the short specialised courses at the post-secondary level. Such courses would give the possibility to obtain vocational qualifications and enter the labour market. As shorter and oriented to the needs of the labour market the courses could be an alternative to the academic, higher education studies. However that ‘next step’ has never been fully and consequently implemented. As it could have been seen in the last decade of the twentieth century the changes of the secondary education in Poland were more the consequence of changes in the economy than the result of the implementation of clearly designed educational policy. That fact was highlighted by the examiners of the OECD review of educational policy in Poland 1995. “The examiners had difficulties in discovering a clear and coherent national strategy concerning VOTEC. They found that such a strategy could only be meaningful if research on VOTEC and its curriculum is improved, if leadership in this field is strengthened.” What the experts saw as an obstacle to the conception and implementation of such a coherent vision of the development of vocational education and training was inter alia the weakness of two units responsible for this sector – the relevant department in the Ministry of Education and the section in the Institute of Educational Research. The examiners encouraged the authorities to make a leap forward and to work out a specifically Polish model of secondary education (covering both general and vocational education) instead of copying arrangements from other countries. There was also little interest in the reform of education shown by social partners: employers and trade unions. With the surplus of jobseekers on the labour market employers did not see any need in investing in training, particularly initial training when they could hire employees immediately with required qualifications, if needed. Such needs were rather rare as most of the enterprises reduced their staff. The trade unions were concentrated on the job protection, negotiations of the social guaranties for the employees of privatised state-owned companies, leaving aside the issues of training and qualifications. The reform of 1998 Shortly after the parliamentary elections in 1997, new government presented a package of four reforms covering: the pension system, administration, health and education. The aims and preliminary concept of the reform of the education system were defined in a policy document presented by the Minister of National Education in January 1998. The following goals were set for the reform1: • raising the level of educational attainment in the society by increasing the number of those holding secondary and higher education qualifications; • ensuring equal educational opportunities; • supporting improvement in the quality of education viewed as an integral process of upbringing and instructing. The necessity to carry out a comprehensive reform of the education system was justified 1 Ministry of National Education, „ Reform of the education system – proposal”, WSiP, Warsaw, 1998. in the document by: • the lack of capacity within the existing education system to adapt to the pace and scope of cultural and social change; • the crisis of the educational role of the school resulting from the predominance of the transmission of information over the development of skills and the shaping of personality; • the lack of equal opportunities in the access to education at all its levels and the low percentage of young people completing secondary and higher education; • the necessity to adapt vocational education to the changing needs of the market economy; • the need to establish closer links between schoolsat all levels and the family as well as the local community. The reform was envisaged to cover the following areas: • the introduction of a new structure of the school system; • changes in the methods of administration and supervision; • a curricular reform comprising the introduction of core curricula and changes in the organisation and methods of teaching; • the establishment of an assessment and examination system independent of the school; • the financing of schools; • the identification of qualification requirements for teachers that would also be linked with their promotion paths and the system of remuneration at an adequately high level. As shown above, the plan presented a reform covering all aspects of the education system. Proposals for specific arrangements were centred on school education. Structural Reform A change in the structure of the school education system, including the introduction of the gymnasium as a new type of schools, was the most visible to the society and became the symbol of the whole reform. It was decided that the previous structure of education, comprising the eight-year primary school followed by the four-year secondary school or the three-year vocational school as an option to be chosen, would be replaced with a system described in brief as „6+3+3” (Graph 2.). This meant that the duration of education in the primary school would be reduced to 6 years. Following the educational cycle in the primary school, the pupil would continue his/her education in a three-year gymnasium, and only upon completion of education in the gymnasium would he/she move on to a three-year secondary school (specialised lyceum) or a two-year vocational school. The structural reform postponed the choice of the direction of education at the secondary level (general or vocational stream) for one year. Pre-school education 0 I II III IV V VI I II III I II III IV "zero" class primary school Lower secondary Gymnasium General second. (profiled) Basic vocat. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Graph 2. The school education system proposed by the reform of 1998 Far-going transformations were also envisaged for the secondary school. It was assumed that the most, i.e. 80%, of those graduating from gymnasia would continue their education in lyceums, and 20% would opt for a two-year vocational school. Technical secondary schools would disappear completely from the Polish school education landscape, and lyceums would establish “specialisations”. Lyceum students would be given the choice between the so-called academic option, preparing them to take up higher education courses, and the vocational option, providing them with introductory vocational training to take up employment. Those completing education in a specialised vocational lyceum would not obtain any formal vocational qualifications. Its graduates would need to acquire them in post-secondary schools, at courses or at a workplace. Since the two-year vocational school did not offer its students the possibility to take the maturity examination, two-year supplementary lyceums would be established to enable those graduating from such schools to continue their education. The structural reform (introduction of the gymnasium) was launched in September 1999. The first group of students after the completion of the 6th grade of the primary school started their education in the first grade of the lower secondary school – gymnasium. At the same time the new curriculum was introduced in primary schools and – of course – in the first grade of gymnasium. It was planned that the new curriculum would “advance” grade by grade together with the first age group of gymnasium students. Effectively by 2002 the reform should have “entered” the upper secondary schools. The introduction of a curricular reform based on a far-going decentralisation required a system for the collection of information and the monitoring of the school education system being implemented simultaneously. It was therefore decided that common compulsory tests assessing pupil achievements should be organised at the end of education in the primary school and at the end of education in the gymnasium. School education would culminate with the maturity examination taken upon completion of education in the lyceum. All these examinations were to be organised, set and corrected by the central examination board and regional examination boards, new institutions to be set up as part of the reform. It should have. But in 2001 there were parliamentary elections in Poland. The major party of the new governing coalition was the Alliance of the Democratic Left (social-democrats with the roots in the communist party). Many members of the Parliament from this party were members of the Union of Polish Teachers - the biggest teacher trade union. Teachers, particularly teachers of vocational subjects in secondary schools were very concerned that closing technical schools would cause a reduction of the number of jobs. They did not believe (partly they were right) that there would be opportunities to be employed in the developing post-secondary and further education and training. There were not trained to work with adult trainees and with more flexible curricula. As a result of that informal lobbing the very first decisions of the Government taken only few weeks after the elections concerned the delay for 3 years of the introduction of so called ‘new matura’ and of the structure of the upper secondary education. It was decided that secondary vocational schools (technika) would survive alongside profiled lycea and vocational schools. (Graph 3.) Pre-school education 0 I II III IV V VI I II III I II III IV "zero" class 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 primary school Lower secondary Gymnasium General Profiled Second. second. lyceum vocat. 3 4 5 13 14 15 Basic 16 vocat. 17 18 19 Graph 3. The structure of the school education introduced in 2001 PISA results in 2000 and 2003 Although it was not planned beforehand Poland got a very strong instrument to measure the effects of the structural reform. It was OECD international survey of students achievements known as PISA – Programme for International Students Assessment. The programme launched in 2000 measures every 3rd year the competences of 15-year olds in reading literacy, mathematics and science. In Poland in 2000 most of the 15-year olds were in the first grade of post-primary schools as the reform introduced in 1999 did not affect that age group. The distribution of students from different types of schools in the survey sample was similar to the pattern in the whole age group: 40.7% of general secondary lycea, 36.4% of secondary vocational schools and 22.9% of basic vocational schools. In 2003 when the second cycle of PISA take place almost all 15-year olds attended the last grade of the lower secondary school – gymnasium. The average result achieved by Polish 15-year old students in PISA 2000 test was 479 points what was significantly lower than the OECD average – 500 points. Polish results were characterised by standard deviation of the reading literacy scores equalled to 100% (it means equal to the OECD average variance of students scores) and big variation between schools – 63% (OECD average 35%). There was a big group of students (21.4%) who achieved very low results (below 400). That group was unequally distributed among different types of schools: 80 600 70 500 percent 60 400 50 40 300 30 200 20 100 10 0 0 General secondary Secondary vocational Basic vocational points (500 - OECD average) PISA 2000 POLAND Percentage of the students with the score below 400 Percentage of the students the score beyond 600 Average student score (points) Type of school General secondary Secondary vocational Basic vocational POLAND Percentage of the Average student score students with the (points) score below 400 544 2.2 476 13.8 362 69.5 479 21.4 Percentage of the students the score beyond 600 22.0 3.6 0.0 10.6 As it can be seen the general secondary schools students performed as good as their colleagues in Finland the country that achieved the best results (546 points). On the other hand 70% of the basic vocational schools students demonstrated the competences at the lowest literacy level or even below (or more precisely, they did not demonstrate any competences in functional literacy). The results clearly indicated that the Polish post-primary schools were very differentiated and that there was a strong selection at the threshold between the primary and secondary levels of education. Strange enough, neither low overall scores of Polish students in PISA 2000 nor the alarming signals on selection at the secondary level have provoked debate in Poland. The results of the survey were published in 2001 when, after the parliamentary elections and the change of the government, ‘corrections’ to the educational reform were decided upon and introduced. Among them there was the decision on maintaining the structure of the secondary education with 4 types of schools: general lycea, profiled lycea, secondary vocational and basic vocational. The government did not pay attention to the simple rule repeated by some experts: the more different options the more selection and the bigger inequalities. No programmes were proposed to equal the difference and particularly to focus on the students in basic vocational schools. The evidence how the selection may affect students’ achievements has been brought by the next cycle of PISA conducted in 2003. The average score of Poland increased from 479 in 2000 to 497points what was at the level of the OECD average. There were only 15% of students who scored 400 point or less (21.4% in 2000) and 13.7 with 600 or more points (10.6% in 2000). At the same time the total variance of the students performance (as a percentage of the average OECD variance) was 94.7% (100% in 2000), the variance between schools 12.0 and variance within schools 83.1 (63 in 2000). The latter results are not surprising if we remember that in 2003 the 15-year olds were in uniform comprehensive lower secondary schools. But how to explain the noticeable improvement of the results of so called ‘lower quarter’ of the students? The researchers have tried different hypothesis looking for correlations between the improvement of students performance and the school resources, the quality of school equipment, teachers’ qualifications, selection and class groups composition, the student teacher ratio and the school size. No correlation has been identified. There are two possible explanations. One is that basic vocational schools students ‘labelled’ as low achievers did not make much effort to solve the problems at PISA test. While in the mixed classes in lower secondary schools the attitude was different and even weaker students tried to perform as good as they could. The other convincing explanation refers to the introduction of the national tests in Polish schools in 2002. The “PISA students” of 2003 had gained experience in solving test sitting the final test of the primary school and being trained for the final exam (also in a form of a test) of gymnasium. The 15-year old student of 2000 did not have such experience. Only those who attended secondary school had passed the entrance exams which were rather similar to traditional class exercise than to the questionnaire used for PISA. Matura 2005, 2006, 2007 External examinations were the backbone of the school education system reform introduced in 1999. They were planned as an objective tool for the evaluation of student's and school achievements helping local authorities to assure good quality of the educational services. The new exams were intended to facilitate the introduction of the curriculum reform as well. The national core curriculum defined the goals, the objectives and the outcomes of teaching and learning. All decisions on measures and methods to achieve them were left to schools and teachers. The examination standards served as principle guidelines for planning the educational process. In the new school system the exams (tests) are organised at the end of each level of schooling: in the sixth grade of the primary school, the third grade of the lower secondary school and in the last grade of the upper secondary school. The final test of the primary school gives feedback information to individual pupils and to schools on their achievements. This test is not meant for any selection as all primary school graduates have to continue their education in the compulsory gimnazjum (lower secondary school). The results of the exam taken in the third grade of gimnazjum are used together with the final marks for the selection of candidates to upper secondary schools. New Matura, the secondary school leaving examination, replaced entrance examinations to the higher schools (universities). All three exams are designed, organised and run by the regional examination boards (Okręgowe Komisje Egazminacyjne) and the Central Examination Board (Centralna Komisja Egzaminacyjna). So the examiners and assessors are not anymore the teachers of the given school. The first exams organised according to the new rules were planned to take place in 2002 – three years after the introduction of the reform and at the time of the completion of the full three year cycle of the primary (beyond elementary – grades 1–3) education, the lower secondary as well as upper secondary education. Both final tests in primary schools and lower secondary were organised according to the plans. New matura suffered from the political changes – the government formed after the 2001 parliamentary elections decided to postpone the introduction of this exam till 2005. In that year, only students of general and profiled upper secondary schools sit the new Matura exams. The education in upper secondary vocational schools lasts for 4 years so the first graduates of gymnasia who continued their education in secondary vocational schools in 2005still had one year of education in front of them. The first new Matura was passed by 87% of those who applied. One has to remember that Matura is not obligatory so not all graduates (or potential graduates) decide to apply. Unfortunately, the data on the number of graduates provided by the Central Statistics Office and the data from the Central Examination Board are not consistent so its difficult to calculate the matura success rate in the relation to the number of graduates or – what would be even more interesting – to the number of the students who started their education in the given school three years earlier. Almost ninety percent of passed exams is a good result. It was not so good in the case of profiled lycea – only 67% of successfully passed exams, while 92% of their colleagues from general secondary achieved positive results. Such differences should not surprise if we take into account that only the best graduates of the lower secondary schools applied for general secondary schools. Profiled lycea were the second or even the third (after secondary vocational schools) option. Also the number of lessons of general subjects (assessed at Matura) in profiled lycea was smaller than the corresponding number in general secondary schools. So the lower results in profiled secondary schools could have been foreseen. However, one third of those who did not passed prove that profiled lycea did not manage to compensate for and reduce the deficits of their first grade students during three years of schooling (in comparison to the students attending general secondary schools). Yet the Ministry was (rightly) proud of the success of the complicated logistic operation “New Matura” (240 thousands students) and there was not enough attention paid to the poor results of profiled schools graduates. It is worth mentioning that 2005 was also the year of the parliamentary elections, so the government tended rather to concentrate on success than problems. In the following year Matura was organised in general secondary schools, profiled general secondary schools and in secondary vocational schools. The overall success rate was lower than in the previous year – 79%. In general secondary schools it was 90%, in profiled lycea 62% and in secondary vocational 66%. Poor achievements rose the concern of the new minister of education who decided that the best way to improve the results was to reinterpret the regulations. The rule that the student to pass the exam had to gain at least 30% of points in each of the taken subjects was replaced by regulation that 30% of all points (from all partial exams) was enough to pass. Consequently, the results in the following year 2007 were better: general secondary schools - 90%, profiled lycea - 70%, vocational secondary schools – 82%. At least the statistics looks better. Higher education institutions evidently have serious doubts on the competences of their perspective students and from this year on some universities have initiated special courses for the first year students to compensate for their deficits in knowledge particularly in mathematics. That all has been caused by the lack of systematic approach. Instead of addressing the problem at the secondary education level (where it emerged) the efforts are made to “repair” the situation at the tertiary level. Percentage of passed Matura (types of schools) 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 2005 General 2006 Profiled 2007 Vocational ANNEX – Statistical Data Distribution of first grade students among different types of secondary schools before 1989 Year Type of school Secondary general education lycea Secondary vocational Basic vocational 1972 15.0 21.5 63.5 1986 18.0 30.5 51.5 Number of students 3 500 3 000 2 500 2 000 1 500 1 000 500 0 1990/1991 199 5/1996 1998/1999 2002/2003 2003/2004 school year General secondary post-secondary basic vocational Schools for adults secondary vocational Students in (upper) secondary education 1995/1996 2000/2001 1990/1991 Total femal male Secondary schools (old system 8+3/4/5) 2 233 037 Basic vocational schools Total femal male 2 585 905 Total femal 2003/2004 male 2 968 631 Total femal 2006/2007 male 1 286 743 Total femal male 32 448 835 969 305 812 530 157 729 886 263 024 466 862 555 426 188 749 366 677 27 372 8 526 18 846 457 59 398 for youth for adults 832 026 304 360 527 666 3 943 1 452 2 491 721 860 261 643 460 217 8 026 1 381 6 645 541 951 185 585 356 366 13 475 3 164 10 311 18 252 9 120 6 230 2 296 12 022 6 824 457 59 398 General secondary (lyceum) 493 625 357 105 136 520 756 023 504 014 252 009 1 053 635 642 697 410 938 401 906 220 727 181 179 18 914 8 631 10 283 for youth for adults 445 018 323 405 121 613 48 607 33 700 14 907 682 997 464 503 218 494 73 026 39 511 33 515 924 178 579 410 344 768 129 457 63 287 66 170 250 030 152 239 151 876 68 488 97 791 83 388 18 914 8 631 10 283 618 211 337 535 280 676 768 920 378 942 389 978 928 658 436 138 492 520 354 203 168 996 185 207 1 910 918 992 578 334 313 674 264 660 39 877 23 861 16 016 757 135 372 738 384 397 11 785 6 204 5 581 904 455 422 142 482 313 24 203 13 996 10 207 336 720 159 607 177 113 17 483 9 389 8 094 158 1 752 47 871 111 881 176 801 55 870 120 931 169 211 39 600 129 611 228 885 64 990 163 895 235 896 68 779 167 117 11 167 3 109 8 058 58 261 118 540 15 062 40 808 43 199 77 732 18 290 21 310 52 149 77 462 59 827 169 058 15 816 44 011 49 174 119 884 68 904 166 992 19 633 49 271 49 146 117 846 11 167 3 109 8 058 108 285 83 206 25 079 161 010 113 965 47 045 200 114 130 132 69 982 265 744 156 072 109 672 75 134 33 151 55 568 27 638 19 566 5 513 96 159 64 851 70 719 43 246 25 440 21 605 78 792 121 322 56 722 73 410 22 070 47 912 90 511 175 233 59 969 96 103 30 542 79 130 146 81 65 855 na na 1 913 693 1 220 1 622 755 867 Secondary vocational schools (technikum) for graduates of 8-year primary schools for youth for adults Secondary vocational schools (technikum) for graduates of basic vocational schools for youth for adults Postsecondary schools (szkoła policealna) for youth for adults Special vocational schools Upper secondry schools (new system 6+3+3) Basic vocational schools for youth for adults 70 439 98 772 1 401 414 2 220 502 185 743 59 578 126 165 235 975 67 013 168 962 185 743 - 59 578 126 165 - 229 170 6 805 65 352 163 818 1 661 5 144 General secondary (lyceum) 520 785 309 885 210 900 885 651 506 754 378 897 for youth for adults 501 804 302 044 199 760 18 981 7 841 11 140 732 908 442 207 290 701 152 743 64 547 88 196 173 195 170 462 Profiled general secondary schools na na 95 642 74 820 for youth for adults Secondary vocational schools (technika) for youth for adults Postsecondary schools (Szkoła policealna) 170 176 3 019 91 635 na 78 541 na 255 947 na na 593 520 223 126 370 394 97 903 156 250 na na 534 831 205 833 328 998 58 689 17 293 41 396 254 153 1 794 90 874 4 768 69 089 5 731 327 876 167 867 160 009 for youth for adults 58 819 35 649 23 170 269 057 132 218 136 839 Special vocational schools Total 159 963 10 499 7 018 2 233 037 Central Statistics Office (GUS), on the 30 September of the given year 2 585 905 2 968 631 2 688 157 2 252 950 3 047 3 971