Selling it First, Stealing it Later: The Trouble with Trademarks in

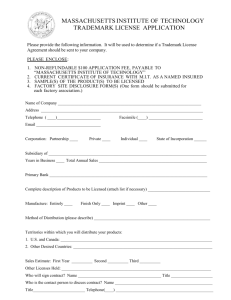

advertisement