Building India: Accelerating infrastructure projects

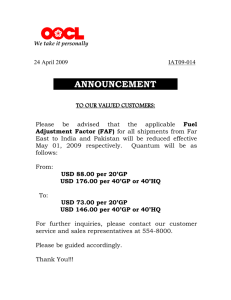

advertisement