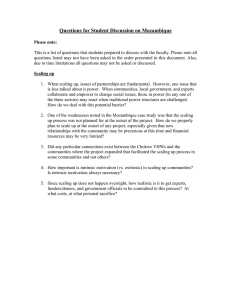

Strategies for scaling social innovations

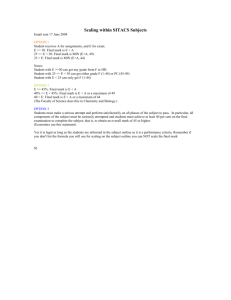

advertisement