Electroconvulsive therapy for depression (Protocol)

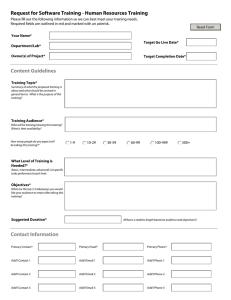

advertisement