Management of Delirium in Critically Ill Older Adults

advertisement

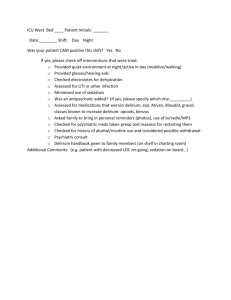

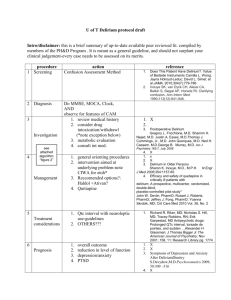

Cover Article Management of Delirium in Critically Ill Older Adults Michele C. Balas, RN, PhD, APRN-NP, CCRN Michael Rice, RN, PhD, APRN-NP Claudia Chaperon, PhD, APRN-NP Heather Smith, PT, MHS, MPH Maureen Disbot, RN, MS, CCRN Barry Fuchs, MD Delirium in older adults in critical care is associated with poor outcomes, including longer stays, higher costs, increased mortality, greater use of continuous sedation and physical restraints, increased unintended removal of catheters and self-extubation, functional decline, new institutionalization, and new onset of cognitive impairment. Diagnosing delirium is complicated because many critically ill older adults cannot communicate their needs effectively. Manifestations include reduced ability to focus attention, disorientation, memory impairment, and perceptual disturbances. Nurses often have primary responsibility for detecting and treating delirium, which can be extraordinarily complicated because patients are often voiceless, extremely ill, and require high levels of sedatives to facilitate mechanical ventilation. An aggressive, appropriate, and compassionate management strategy may reduce the suffering and adverse outcomes associated with delirium and improve relationships between nurses, patients, and patients’ family members. (Critical Care Nurse. 2012;32[4]:15-26) CNEContinuing Nursing Education This article has been designated for CNE credit. A closed-book, multiple-choice examination follows this article, which tests your knowledge of the following objectives: 1. Identify risk factors for delirium in critically ill older adults and the common barriers to its early recognition 2. Describe the symptoms, possible causes, and potential clinical consequences of delirium in critically ill older adults 3. Discuss the nursing implications associated with both pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods of prevention and management of delirium in critically ill older adults ©2012 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ccn2012480 www.ccnonline.org M ore than one-half of all intensive care unit (ICU) days are incurred by adults 65 years and older.1 Unfortunately, once admitted to an ICU, older adults are at high risk for delirium.2,3 Often referred to as “acute cognitive dysfunction,”4 delirium is a common and serious geriatric syndrome in the ICU. Formally, delirium is defined as an acute but temporary state of fluctuating levels of consciousness and pervasive impairment in mental, behavioral, and emotional functioning.5 The manifestations can be extremely upsetting to patients, patients’ families, and nursing staff. Delirious patients may experience visual and auditory hallucinations, are impulsive, are often disoriented, and often have self-injurious behaviors.6 These behaviors potentially increase the risk for poor outcomes. Nurses play an essential role in the management of delirious, critically ill older adults. Nurses are often the interdisciplinary team members who first notice that an elderly patient is experiencing a change in mental status; determine whether the patient is experiencing other indications of distress such as pain, anxiety, or dyspnea that may cause or contribute to the behavioral changes; and intervene by using the best available evidence to promote the comfort, safety, and welfare of the patient. This process is extraordinarily complicated because many older adults are voiceless due to their critical illness, CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 15 et al3 found that Table 1 Outcomes associated with delirium in the intensive 62% of the care unit (ICU) patients had Higher ICU and hospital costs evidence of Longer ICU and hospital length of stay delirium during Greater use of continuous sedation and physical restraints the ICU stay. In 2 a similar study Increased unintended self-removal of catheters and self-extubation of older adults Higher ICU, hospital, and 6-month mortality rates in a surgical ICU, 30% of to extend to the time after discharge patients experienced delirium sometime during their ICU stay. Of note, in from the hospital. In a surgical ICU, older patients with delirium were both of these studies, older adults more likely than patients without were screened not only for delirium delirium to be discharged to a place (via the Confusion Assessment other than home (61.3% vs 20.5%; P Method for the Intensive Care Unit; 12 <.001) and have greater functional CAM-ICU ) but also for preexisting decline, as measured by the Index of cognitive impairment, which is now Frequency and Outcomes ADL,22 (67.7% vs 43.6%; P=.02).23 In recognized as an important predictor Associated With Delirium this study,23 delirium was strongly of delirium.13 These reports suggest Delirium is a common and frequent manifestation of acute brain that delirium rates in older patients in and independently associated with 9 greater odds of being discharged to dysfunction. The reported prevamedical and surgical ICUs may vary widely, depending on the type of unit. any place other than home (odds lence of delirium in critically ill adults 10,11 ratio, 7.20; 95% CI, 1.93-26.82). In Further study is warranted to deterranges widely, from 11% to 87%. another study24 of older medical mine if these variations persist. Few investigators have exclusively ICU patients, after adjustments Delirium in the ICU is associated examined the occurrence and durawith a wide array of poor patient out- were made for relevant covariates, tion of delirium in critically ill older including age, severity of illness, comes (Table 1). The effect of deliradults. In a study of older adults ium on critically ill older adults seems comorbid conditions, use of psyadmitted to medical ICUs, McNicoll choactive medication while in the ICU, and baseline cognitive and functional status, the number of Authors Michele C. Balas is an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, days of ICU delirium was signifiCollege of Nursing, Omaha, Nebraska. cantly associated with time to death Michael J. Rice is a professor of psychiatric nursing and the associate medical director of within 1 year after admission to the the Behavioral Health Education Center for Nebraska at the University of Nebraska MedICU (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, ical Center, College of Nursing. 1.02-1.18). These findings indicate Claudia Chaperon is an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, that delirium is a burden not only College of Nursing. for critically ill older adults, who Heather Smith was manager of core measures at New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York, when this study was done. She is now program director for quality at the American face marked disability and altered Physical Therapy Association in Alexandria, Virginia. quality of life, but also for the Maureen Disbot is vice president of quality operations, Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas. patients’ family caregivers. mechanical ventilation, and the sedative effects of medications used in the ICU to facilitate care.7 Furthermore, critical care nurses are practicing in an environment where health care providers are just beginning to fully appreciate the prognostic importance of delirium.8 In this article, we review current evidence pertinent to delirium in critically ill older adults and describe pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches nurses can use to manage the distressing physical, psychological, and emotional manifestations of delirium in older patients. Barry Fuchs is an associate professor, Department of Medicine, Perlman College of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Corresponding author: Michele Christina Balas, RN, PhD, APRN-NP, CCRN, 4903 N 142nd St, Omaha, NE 68164 (e-mail: mbalas@unmc.edu). To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact The InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Phone, (800) 899-1712 or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax, (949) 362-2049; e-mail, reprints@aacn.org. 16 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 14 2,15-17 18 19 16,20,21 Risk Factors Delirium in ICUs was originally thought to be caused by environmental factors unique to the units, www.ccnonline.org Table 2 Risk factors for delirium Risk factors Setting (population) Nonmodifiable Potentially modifiable Hospital (older adults)5,27-30 Dementia/cognitive impairment Severity of illness Advanced age Male sex Preadmission institutionalization Social isolation History of depression Fever, low blood pressure Hearing and visual impairments Diminished activities of daily living Multiple abnormal results of laboratory tests Unplanned surgery/type of surgery Alcohol abuse Fracture at time of admission Increased number of admissions in the past year Preadmission malnutrition Use of physical restraints Medication use (see following) Low mobility after surgery Malnutrition Sensory impairment Iatrogenic events (defined as cardiopulmonary complications, hospital-acquired infections, medication related, complications of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, unintentional injury) Critical care (adults)5,10,19,25 Comorbid conditions Preoperative psychiatric illness History of smoking Multiple abnormal results on laboratory tests Infections Fever Advanced age Severity of illness Medications (eg, mean daily dose of morphine, larger daily doses of both fentanyl and midazolam) Windowless units Intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay Sleep deprivation Infections Critical care (older adults)13,31,32 Dementia Receipt of benzodiazepines before ICU admission Elevated creatinine levels Low arterial pH Severity of illness such as sleep deprivation, sensory overload, and lack of windows.16,25-27 More recent evidence5,10,19,25,27-30 suggests that risk factors associated with delirium in critical care are similar to those in other hospitalized older adults (Tables 2 and 3). Of note, some of these variables are fixed (eg, age, diagnosis), whereas others may be amenable to nursing intervention. Several interrelated patient characteristics are associated with delirium in older ICU patients. Pisani et al31 identified 4 preexisting risk factors for delirium in older patients admitted to medical ICUs: dementia, administration of benzodiazepines before ICU admission, elevated serum creatinine levels, and low arterial pH. The relationship among medications, www.ccnonline.org Receipt of a benzodiazepine, an opioid, or haloperidol physiological Table 3 Medications associated with deliriuma derangements, Anesthetics and delirium in Analgesics older ICU Antiasthmatic agents Anticonvulsants patients was Antihistamines also reported Antihypertensive and cardiovascular medications for another Antimicrobials Antiparkinsonian medications study32 by Benzodiazepines Pisani and colCorticosteroids Gastrointestinal medications leagues. These Muscle relaxants researchers Immunosuppressive agents were interested Lithium Psychotropic medications with anticholinergic properties in examining a Based on information from American Psychiatric Association. modifiable risk factors for delirdelirium in older ICU patients. ium in the ICU. They found that These findings indicate the need administration of a benzodiazepine, for screening for preexisting cognian opioid, or haloperidol; preexisttive impairment, judicious use of ing dementia; and severity of illness medications, and prevention of were associated with the duration of 5 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 17 secondary physiological injuries in critically ill older adults. Definition and Clinical Manifestations The gold standard for diagnosis of delirium is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR).5 The DSM-IV-TR defines delirium as a disturbance of consciousness, attention, and perception that develops over a short time (usually hours to days) that can fluctuate during the course of the day.5 The manual emphasizes that delirium often develops as a sudden decline from the previous level of functioning rather than with the gradual decline associated with dementia. The 4 DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for delirium are given in Table 4. Delirium is manifested by disturbances in consciousness, orientation, speech, and perception and by neurological abnormalities. The disturbance in consciousness is manifested as a reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. Behaviorally, a patient with delirium is easily distracted and often difficult to engage in conversation. In contrast, cognitive changes associated with delirium are characterized by impaired memory, visual spatial impairment, disorientation, and language disturbances. Progressive loss of orientation is often a cardinal indication of the onset of delirium. Disorientation to time is one of the first indications of cognitive decline; next are disorientations to place, person, and self. Speech and language disturbances can also occur in delirium, and include dysarthria, dysnomia, dysgraphia, and even aphasia.5 Perceptual disturbances involve 3 main areas: misinterpretations, 18 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 Table 4 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) criteria for deliriuma 1. Disturbance of consciousness with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. 2. A change in cognition or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia. 3. The disturbance develops over a short time (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day. 4. Evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings indicates that the disturbance is caused by some direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition, by a toxic substance, by use of medications, or by more than one cause. a Based on information from American Psychiatric Association.5 illusions, and hallucinations. Although visual hallucinations are common,33 misperceptions associated with other senses, including auditory, tactile, and olfactory, also occur. Initial neurological manifestations of delirium include disturbances in the sleep-wake cycle, activity levels, and emotional responses and multiple nonspecific neurological abnormalities (eg, tremor, myoclonus, asterixis, reflex changes, and electroencephalographic abnormalities).5,33 Neurological disturbances are often dramatic, fluctuating, and disturbing to witness. The psychomotor behaviors of delirious patients are often classified into 3 subtypes: hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed.34-37 Behaviors associated with the hyperactive form may be particularly disturbing; these include screaming out in fear, describing hallucinations, pulling at tubes, trying to climb out of bed, and attempting to hit staff. In stark contrast, the hypoactive form of delirium may be missed in the absence of active monitoring and is more common in older, seriously ill patients. Elderly patients with the hypoactive form may be deemed “easier to care for” because they often lie quietly in their bed and are withdrawn or lethargic. In one study35 in an ICU, the purely hyperactive form of delirium was rare (1.6%); the hypoactive (43.5%) and mixed (54.9%) forms were far more common. The transient nature and multiple manifestations of delirium often complicate accurate diagnosis. Challenges in Diagnosis Intensive care providers have historically observed dramatic changes in cognitive and neurobiological function in critically ill older adults. Unfortunately, a lack of conceptual clarity continues to exist in describing the exact nature of these changes. For example, delirium in the critical care setting often is referred to as ICU psychosis, ICU syndrome, or sundowning.38 The variable definitions and terminology used to describe delirium inhibit effective communication and research on this condition.38 Delirium continues to be overlooked, misdiagnosed as dementia (a more chronic form of cognitive dysfunction), psychiatric illnesses such as depression, and decline attributed to normal aging.28 A lack of familiarity with valid and reliable screening tools used to diagnose delirium in the ICU may also contribute to either missed diagnosis or underdiagnosis. www.ccnonline.org In the ICU, voicelessness, or the inability to speak, is often due to the effects of intubation and mechanical ventilation, sedation, or the frequent cognitive, sensory, and physiological imbalances that often accompany critical illness.39-41 These effects make it difficult to detect delirium in voiceless patients. Restrictions in the amount of time family members of critically ill older patients can spend with the patients also potentially influence delirium detection rates, because a patient’s family members are often the first to recognize the patient is experiencing a change in mental status. Not having the same patient on a consistent basis and the multiple changes in caregivers that occur in the ICU environment are also inherent problems in the recognition of delirium. These barriers impede early recognition, delaying timely and appropriate intervention. Detection of Delirium Screening for Preexisting Cognitive Impairment Several tools42-59 are available to nurses to aid in the differential diagnosis of delirium in critically ill older patients (Table 5—available online only, at www.ccnonline.org). Because dementia is a known risk factor for delirium in the ICU and the development of delirium may actually hasten or accelerate the development of dementia-like syndromes,60 ICU clinicians should consider routinely screening patients for evidence of preexisting cognitive impairment.31 Pisani et al31 suggest that knowledge of a patient’s dementia status will not only make ICU staff more cognizant of the www.ccnonline.org risk for delirium but also alert them to factors that contribute to delirium, such as use of physical restraints and use of certain anticholenergic medications. Effective screening instruments for detection of preexisting cognitive impairment in older critically ill patients include the short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly42 and the Modified Blessed Dementia Rating Scale.43 Monitoring for Contr ibutor y Symptoms Critically ill older adults experience several other symptoms and syndromes that may contribute to the development of delirium. The contribution of these other entities is reflected in the clinical practice guidelines of the Society of Critical Care Medicine61 for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in critically ill adults. The guidelines state that all ICU patients should be regularly assessed for pain, sedation, delirium, and sleep disturbances by using scales or tools that are both validated and appropriate to older patients. The society further recommends that this assessment be performed sequentially; that is, providers should first assess and treat pain, and the sedation of agitated critically ill patients should be started only after the patients have been provided adequate pain relief and treatment of reversible physiological causes. Performing Regular Assessments Several delirium detection tools have been validated in critically ill populations (see Table 5—online only). Of note, however, the scales differ substantially in the quality and extent of validation efforts, the specific components of the delirium syndrome addressed, the ability to differentiate between the forms of delirium, and the ease of use.57,62 One of the most established and widely used tools is the CAM-ICU. This tool11,12 is a modified version of the CAM developed to assist in diagnosing delirium in nonverbal, critically ill patients. The CAM-ICU criteria for a diagnosis of delirium are the same as in the CAM, although some components have been modified. Features 1 (acute onset of mental status change or fluctuating course), 3 (disorganized thinking), and 4 (altered level of consciousness) remain the same. However, for assessment of feature 2 (inattention), the CAM-ICU uses either the Visual (Picture) or the Auditory (Letter) Attention Screening Examination. The CAM-ICU can be administered in less than 2 minutes and is valid and reliable in different ICU settings. More information about the CAM-ICU is available online.38 Another useful tool for evaluating delirium is the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist.55 This tool consists of 8 items based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium: altered level of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, hallucination or delusion, psychomotor agitation or retardation, inappropriate mood or speech, sleep-wake cycle disturbance, and symptom fluctuation. Scores range from 0 to 8. A total score of 4 or greater has 99% sensitivity for a psychiatric diagnosis of delirium. Treatment Options The exact pathophysiology of ICU delirium remains unclear. Its development is thought to be related CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 19 to anatomical deficits; imbalances in the neurotransmitters that modulate control of cognitive function, behavior, and mood; and various inflammatory mechanisms.38 Neurotransmitters, including the monoamines (eg, serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine), and imbalances in acetylcholine, glutamate, and γ-aminobutyric acid are postulated to be involved in delirium.9 Pharmacological treatment of delirium is usually directed toward decreasing agitation and psychotic symptoms.5 Pharmacological Methods A thorough discussion of medication management in critically ill older adults is beyond the scope of this article. A few caveats, however, warrant special attention. First, many medications are associated with the onset of delirium (Table 3). Almost every medication used in the ICU can potentially predispose an older patient to delirium. Ironically, many of the medications used to treat the symptoms of delirium (eg, restlessness, altered sleep cycle) have anticipated side effects that may actually make the symptoms worse. Nurses caring for delirious, older patients should critically review each patient’s record of medications administered for the number and type of medications the patient is receiving and should discuss with the patient’s physician or nurse practitioner the possibility of discontinuing all nonessential medications to limit the total number of drugs administered.7 Implementation of many of the standard geriatric principles of medication management (eg, frequent review of medications used, avoidance of polypharmacy, application of the Beers Criteria and 20 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 concepts)63 may reduce the incidence and severity of delirium in critically ill older patients. Antipsychotic medications are commonly used in the ICU to treat the symptoms of delirium.64 According to the most recent guidelines61 of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, haloperidol is still the preferred agent for the treatment of delirium in critically ill patients. Although the optimal dose and regimen of haloperidol have not been well defined, the guidelines suggest using a loading regimen, starting with a 2-mg dose and then giving doses (double the previous dose) every 15 to 20 minutes while agitation persists. Of note, however, the safety and efficacy of antipsychotic medications, particularly in older adults, have recently been questioned. The level of risk is reflected in the “black box” warning65 of the Food and Drug Administration for use of antipsychotics in elderly patients. This class of medications is not approved for dementiarelated psychosis because of increased mortality risk in elderly patients on conventional or atypical antipsychotics. Most of the deaths are associated with use due to cardiovascular or infectious events. The extent to which the increased mortality can be clearly attributed to antipsychotic vs some patient characteristic(s) is not clear.65 Because of the lack of supporting evidence for the use of antipsychotic medications for delirium in critically ill patients and the potentially life-threatening adverse effects of these medications (eg, torsades de pointes, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, sudden cardiac death), Girard et al66 recently conducted a ground-breaking study to determine the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for treatment of ICU delirium. The hypothesis behind the Modifying the Incidence of Delirium randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial was that use of antipsychotics would improve days alive without delirium or coma. A total of 101 patients were randomly assigned to receive haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo every 6 hours for up to 14 days. The patients were 35 to 68 years old. Frequency of administration of medication was adjusted twice daily according to each patient’s status. The results indicated that compared with placebo, neither haloperidol nor ziprasidone significantly reduced the duration of delirium. Further, patients in the 3 treatment groups spent a similar number of days alive without delirium and coma. Because of the surprising efficacy findings, the researchers66 suggest that more trials are needed to determine whether use of antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in the ICU is appropriate. In another clinically relevant, prospective, randomized study, Devlin et al67 compared the efficacy and safety of scheduled quetiapine to placebo for the treatment of delirium in critically ill patients receiving as-needed haloperidol. The results indicated that use of quetiapine (when added to as-needed haloperidol) resulted in slightly faster resolution of delirium, less agitation, and a greater rate of transfer to home or rehabilitation centers versus other settings. Of note, however, the sample size of www.ccnonline.org this study was small (only 36 patients), a characteristic that may, as the investigators acknowledge, limit the ability to reliably detect differences in any of the efficacy or safety outcomes. Because of these concerns about safety and efficacy, nurses should consider several things before administering antipsychotic medications to delirious, critically ill older patients68 (Table 6). Use of sedatives and analgesics is ubiquitous in the ICU.61 Although often necessary, medications such as benzodiazepines and opioids may increase the risk for delirium,69-71 particularly in critically ill older patients.13,31-32 Because these medications themselves contribute to worsening clinical outcomes, an evidence-based organizational approach referred to as the ABCDE bundle (Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium monitoring and management, and Early mobility and exercise) has recently been suggested.72,73 The goal of this approach is to liberate critically ill adults from the harmful effects of exposure to sedatives by using targetbased sedation protocols, spontaneous awakening trials, and proper choice of sedatives.73 An additional goal is early mobilization,73 which will hopefully reduce delirium and improve neurocognitive outcomes. Nonpharmacological Methods The unstable physiological condition that often precedes or exists at the time of admission of older adults to the ICU is often a nurse’s top priority. One of the most important nonpharmacological interventions nurses can use when caring for a delirious, critically ill older adult is preventing and/or correcting the www.ccnonline.org Table 6 Points to consider when administering antipsychotic medications to critically ill older adults What is the goal of treatment? Is there a particular behavior, such as pulling at tubes, that is being targeted by the antipsychotic medication? If behavior is the target symptom, is the cause of the behavior identifiable and manageable? Does a nonpharmacological approach exist that would be more effective at treating that specific behavior? Does the patient have a contraindication for typical or atypical use of antipsychotic medication ? Has a psychiatric consultation been obtained? Is the medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the target symptoms for elders? Do the side effects of the medication compromise the nutritional or electrolyte status of the patient? What is the patient’s QT interval? unstable physiological and hemodynamic conditions that accompany many of the disorders associated with acute change in mental status (eg, early sepsis).74-77 Removal or reversal and recognition of the underlying cause of delirium remain the cornerstone of treatment.5 Nurses who provide care to an older adult experiencing an acute change in mental status need to mobilize all of their available resources early on. If the patient is not yet in the ICU, mobilization may include activating the hospital’s rapid-response team, immediately notifying the patient’s physician of the change in mental status, and increasing the level of care. Precautions to prevent aspiration and falls and ensure safety should also be started to protect the patient from harm.76 Mobilization of resources is important because a nurse caring for a delirious, critically ill older patient will need to work with other members of the ICU team to determine the cause of delirium. Common tools used in the differential diagnosis of delirium include assessment of vital signs, blood glucose levels, pulse oximetry monitoring, laboratory profiles (eg, chemistry studies, drug levels, urinalysis, and arterial blood gas analysis), chest radiographs and electrocardiograms.75,76 Keeping the patient safe and preventing secondary physiological injury is a top priority in effective management of delirium. Another major obstacle to effectively managing delirium in critically ill, older patients is the major communication challenges experienced by these patients. Recent evidence78 suggests that patients with impaired communication may be at elevated risk for poor outcomes. The inability to communicate one’s needs effectively can be associated with feelings of panic, insecurity, stress, anger, worry, and fear,79,80 feelings that may result in further hormonal and physiological abnormalities. Older adults appear to be at particularly high risk for impaired CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 21 communication in the ICU. In a study by Happ et al41 that included 18 older ICU patients, all 18 patients had impaired vision or wore glasses, but more than half (10) did not have their glasses with them in the ICU. In addition, none of the 3 patients who reported wearing hearing aids had their devices in the ICU. Older adults in this study41 were also more likely to have impaired communication (eg, difficulties with speech, word recall, writing) before hospitalization and were more often delirious and sedated at the time of enrollment in the study than were younger patients. Critically ill, older patients need to be provided with their glasses, hearing aids, or other assistive devices to facilitate early mobilization and safe performance of their activities of daily living. Establishing an effective means of communication with critically ill older patients, their families, and other staff members will provide nurses the opportunity to create the strong social network needed for successful, healthy patient outcomes. Methods of providing critically ill, older patients a way to communicate their needs to staff and family members while the patients are in the ICU include using body language or gestures, touching or pointing, lipreading or using mime, using yesno questions, providing a pencil and paper, establishing eye contact, using blinking, using communica- To learn more about delirium in the critical care setting, read “Impact of a Delirium Screening Tool and Multifaceted Education on Nurses’ Knowledge of Delirium and Ability to Evaluate It Correctly” by Gesin et al in the American Journal of Critical Care, 2012; 21:e1-e11. Available at www.ajcconline.org. 22 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 tion boards, consulting speech language pathologists for speaking valves and other augmentative and alternative communication systems, and encouraging family presence during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation.39,40,81,82 Several other strategies for improving communication with delirious patients have been offered. These techniques include using short, simple sentences; speaking slowly and clearly; identifying oneself by name and calling patients by their preferred names; repeating questions as needed; allowing time for patients to respond; and listening and observing patients’ behavior.74-77,83,84 Encouraging patients to be involved in and in control of as much of their care as possible, using reminiscing, acknowledging patients’ feelings and fears, and providing reassurance not only facilitate effective communication83 but also provide reassurance and increase patients’ self-esteem. In addition, nurses providing care for a critically ill older patient must remember that the patient is not the only person who suffers when the patient becomes delirious. Seeing a loved one confused is often devastating to a patient’s family members. Involving and informing a patient’s significant other of the patient’s change in mental status as early as possible is important.75 Providing emotional support to a patient’s family members is paramount. Family members should be encouraged to visit frequently with the patient and to assist in reorientation and nursing care. Family members are also a vital source of information for determining a patient’s baseline mental functioning and behavior and often are important team members in surveillance of patients.40 Although nursing interventions for delirious hospitalized older patients have been reported recently,85,86 the effect of these interventions on the incidence, duration, and outcomes of delirium have not been determined. Nonpharmacological strategies that may be applicable to delirious, critically ill, older patients are presented in Table 7. Health care providers have called for programs such as the Hospital Elder Life Program to be modified in a way that would benefit critically ill older adults.87,88 Since it was first described in 2000, the Hospital Elder Life Program89 is often used as a strategy of improving inpatient care of older adults. This evidence-based, multicomponent, interdisciplinary program has been successful not only in reducing the incidence of delirium in hospitalized older adults but also as an educational resource, improving hospital outcomes (eg, functional decline), providing nursing education, improving retention of nurses, enhancing the satisfaction of patients and their families, and improving quality of care.90 Conclusion Delirium occurs frequently in critically ill, older patients and is associated with numerous adverse outcomes during and after hospitalization. The safety and efficacy of antipsychotic medications in older adults is questionable, and studies raise the issue of whether this class of medications is appropriate for treatment of delirium in the ICU. Existing evidence also suggests that the use of benzodiazepines may further increase the risk for delirium in critically ill www.ccnonline.org Table 7 Additional nonpharmacological interventions to prevent and manage delirium in critically ill older adults Avoid malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies75,83 Avoid use of physical restraints75,76 Discontinue or remove all unnecessary catheters, tubes, and equipment75,76,83 Keep call bell within patient’s reach at all times Consider “camouflaging” catheters and tubes Provide adequate lighting and limit noise levels75,77 Keep environment calm and uncluttered; avoid overstimulation and unnecessary room changes74-76 Consider moving patient closer to nurse’s station, using a “low” bed and/or constant observation76,77 Consider using distraction techniques such as an activity belt; frequent personal contact with family, friends, and staff; or television programs or music with personal significance to the patient76 Use nonpharmacological strategies for sleep promotion; for example, relaxation tapes, massage75,76,83 Encourage early and frequent mobilization/avoid immobilization74-76 Allow activities that decrease anxiety Encourage participation in activities of daily living75; teach appropriate exercises or strength-training activities Consult physical, occupational, and speech therapy personnel as needed76 Provide patients with a way of communicating their needs to staff and family83 Use reality orientation76; repeat information as necessary; explain the situation, environment, and equipment; listen and observe behavior; acknowledge patients’ feelings and fears76 Provide cognitively stimulating activities adapted to each patient75 Interview consistent caregivers and patient’s family to determine patient’s baseline mental status75 Involve and inform significant other of patient’s change in mental status75 (provide emotional support) Encourage scheduled visits by patient’s family and friends (may be helpful to call in family 24/7)74-76 Treat pain75,76 Consult psychiatry service as needed75,84 older patients. These findings suggest a need to provide ICU nurses with alternatives to sedation that will keep patients from becoming delirious. Although a wide variety of nonpharmacological interventions to prevent and treat delirium in hospitalized older adults have been offered, these interventions have not been tested in an ICU. Removal, reversal, and recognition of the underlying causes of delirium are essential components in its treatment. Critical care nurses who provide care for older adults should use all available resources to establish an effective communication network with the patients, the patients’ www.ccnonline.org family members, and other health care providers to achieve successful, healthy outcomes for patients. CCN Now that you’ve read the article, create or contribute to an online discussion about this topic using eLetters. Just visit www.ccnonline.org and click “Submit a response” in either the full-text or PDF view of the article. Financial Disclosures None reported. References 1. Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34(4):1016-1024. 2. Balas MC, Deutschman CS, Sullivan-Marx EM, Strumpf NE, Alston RP, Richmond TS. Delirium in older patients in surgical intensive care units. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2): 147-154. 3. McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591-598. 4. Pandharipande P, Jackson J, Ely EW. Delirium: acute cognitive dysfunction in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(4): 360-368. 5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. 6. Delirium. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki /Delirium. Modified April 16, 2012. Accessed April 25, 2012. 7. Balas MC, Casey CM, Happ MB. Assessing and managing critically ill older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(7):27-35. 8. Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):825-832. 9. Morandi A, Jackson JC, Ely EW. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(1):43-58. 10. Aldemir M, Ozen S, Kara IH, Sir A, Bac B. Predisposing factors for delirium in the CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 23 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2001; 5(5):265-270. Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370-1379. Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710. Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH. Factors associated with persistent delirium after intensive care unit admission in an older medical patient population. J Crit Care. 2010;25(3):540.e1-540.e7. Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(4):955-962. Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(12):1892-1900. Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik Y. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):66-73. Thomason JW, Shintani A, Peterson JF, Pun BT, Jackson JC, Ely EW. Intensive care unit delirium is an independent predictor of longer hospital stay: a prospective analysis of 261 non-ventilated patients. Crit Care. 2005;9(4):R375-R381. Micek ST, Anand NJ, Laible BR, Shannon WD, Kollef MH. Delirium as detected by the CAM-ICU predicts restraint use among mechanically ventilated medical patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6):1260-1265. Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1297-1304. Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753-1762. Lin SM, Liu CY, Wang CH, et al. The impact of delirium on the survival of mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2254-2259. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. Balas MC, Happ MB, Yang W, Chelluri L, Richmond T. Outcomes associated with delirium in older patients in surgical ICUs. Chest. 2009;135(1):18-25. Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1092-1097. Wilson LM. Intensive care delirium: the effect of outside deprivation in a windowless unit. Arch Intern Med. 1972;130(2):225-226. Sveinsson IS. Postoperative psychosis after heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975; 70(4):717-726. Inouye SK, Schlesinger MJ, Lydon TJ. Delirium: a symptom of how hospital care is failing older persons and a window to improve quality of hospital care. Am J Med. 1999; 106(5):565-573. 24 CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 28. Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Hurst LD, Tinetti ME. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):474-481. 29. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3): 204212. 30. Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275(11):852-857. 31. Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Van Ness PH, Araujo KL, Inouye SK. Characteristics associated with delirium in older patients in a medical intensive care unit. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(15):1629-1634. 32. Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK. Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):177-183. 33. Laurila JV, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Delirium among patients with and without dementia: does the diagnosis according to the DSM-IV differ from the previous classifications? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(3):271-277. 34. Meagher D, Moran M, Raju B, et al. A new data- based motor subtype schema for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008; 20(2):185-193. 35. Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, et al. Delirium and its motoric subtypes: a study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):479-484. 36. Marcantonio E, Ta T, Duthie E, Resnick NM. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):850-857. 37. Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Motoric subtypes of delirium in mechanically ventilated surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1726-1731. 38. ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group. Delirium overview and how to diagnose it. http://www.mc.vanderbilt .edu/icudelirium/. Accessed April 25, 2012. 39. Happ MB, Paull B. Silence is not golden. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29(3):166-168. 40. Happ MB, Swigart VA, Tate JA, Arnold RM, Sereika SM, Hoffman LA. Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Heart Lung. 2007;36(1):47-57. 41. Happ MB, Tate J, Garrett K. Nonspeaking older adults in the ICU: communication will require special strategies [Nursing Counts]. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(5):29-30. 42. Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and crossvalidation. Psychol Med. 1994;24(1):145-153. 43. Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797-811. 44. Pisani MA, Inouye SK, McNicoll L, Redlich CA. Screening for preexisting cognitive impairment in older intensive care unit patients: use of proxy assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):689-693. 45. Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338-1344. 46. Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289(22):2983-2991. 47. Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalonealphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2(5920):656-659. 48. Riker RR, Picard JT, Fraser GL. Prospective evaluation of the sedation-agitation scale for adult critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1325-1329. 49. Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM. Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1994; 22(3):433-440. 50. Devlin JW, Boleski G, Mlynarek M, et al. Motor Activity Assessment Scale: a valid and reliable sedation scale for use with mechanically ventilated patients in an adult surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1271-1275. 51. de Lemos J, Tweeddale M, Chittock D. Measuring quality of sedation in adult mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. The Vancouver Interaction and Calmness Scale: sedation focus group. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(9):908-919. 52. De Jonghe B, Cook D, Griffith L, et al. Adaptation to the Intensive Care Environment (ATICE): development and validation of a new sedation assessment instrument. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2344-2354. 53. Weinert C, McFarland L. The state of intubated ICU patients: development of a twodimensional sedation rating scale for critically ill adults. Chest. 2004;126(6):1883-1890. 54. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. 55. Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859-864. 56. Neelon VJ, Champagne MT, Carlson JR, Funk SG. The NEECHAM confusion scale: construction, validation, and clinical testing. Nurs Res. 1996;45(6):324-330. 57. Devlin JW, Fong JJ, Fraser GL, Riker RR. Delirium assessment in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(6):929-940. 58. Hart RP, Levenson JL, Sessler CN, Best AM, Schwartz SM, Rutherford LE. Validation of a cognitive test for delirium in medical ICU patients. Psychosomatics. 1996;37(6):533-546. 59. Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J. A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res. 1988;23(1):89-97. 60. Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Hart RP, Hopkins RO, Ely EW. The association between delirium and cognitive decline: a review of the empirical literature. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004; 14(2):87-98. 61. Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):119-141. 62. Pisani MA. Delirium assessment in the intensive care unit: patient population matters. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):131. www.ccnonline.org 63. Ballentine NH. Polypharmacy in the elderly: maximizing benefit, minimizing harm. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31(1):40-45. 64. Ely EW, Stephens RK, Jackson JC, et al. Current opinions regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):106-112. 65. Haloperidol drug monograph: black box warnings. https://online.epocrates.com/u /10b220/haloperidol/Black+Box+Warnings/. Accessed April 26, 2012. 66. Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428-437. 67. Devlin JW, Roberts RJ, Fong JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):419-427. 68. Balas MC. Free your MIND and the rest will follow: decoding delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):697-698. 69. Pandharipande PP, Sanders RD, Girard TD, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine versus lorazepam on outcome in patients with sepsis: an a priori-designed analysis of the MENDS randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):R38. 70. Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, et al. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644-2653. 71. Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1): 21-26. 72. Pandharipande P, Banerjee A, McGrane S, Ely EW. Liberation and animation for ventilated ICU patients: the ABCDE bundle for the back-end of critical care. Crit Care. 2010; 14(3):157. 73. King MS, Render ML, Ely EW, Watson PL. Liberation and animation: strategies to minimize brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010; 31(1):87-96. 74. Foreman MD, Mion LC, Tryostad L, Fletcher K. Standard of practice protocol: acute confusion/delirium. NICHE faculty. Geriatr Nurs. 1999;20(3):147-152. 75. Michaud L, Bula C, Berney A, et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):371-383. 76. Potter J, George J, Guideline Development Group. The prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people: concise guidelines. Clin Med. 2006;6(3):303-308. 77. Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium: an evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):14051412. 78. Patak L, Wilson-Stronks A, Costello J, et al. Improving patient-provider communication: a call to action. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(9): 372-376. 79. Pennock BE, Crawshaw L, Maher T, Price T, Kaplan PD. Distressful events in the ICU as perceived by patients recovering from coro- www.ccnonline.org 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. 89. 90. nary artery bypass surgery. Heart Lung. 1994; 23(4):323-327. Menzel LK. Factors related to the emotional responses of intubated patients to being unable to speak. Heart Lung. 1998;27(4): 245-252. Happ MB. Communicating with mechanically ventilated patients: state of the science. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12(2):247-258. Wojnicki-Johansson G. Communication between nurse and patient during ventilator treatment: patient reports and RN evaluations. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17(1): 29-39. Rapp CG, Mentes JC, Titler MG. Acute confusion/delirium protocol. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001(4):21-33. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999; 156(5 suppl):1-20. Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF, Schoenfelder DP. Acute confusion/delirium. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):11-18. Flood M, Buckwalter KC. Recommendations for mental health care of older adults, part 2: an overview of dementia, delirium, and substance abuse. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009; 35(2):35-47. Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008;12(suppl 3):S3. Pun BT, Ely EW. The importance of diagnosing and managing ICU delirium. Chest. 2007;132(2):624-636. Inouye SK. Prevention of delirium in hospitalized older patients: risk factors and targeted intervention strategies. Ann Med. 2000; 32(4):257-263. Inouye SK, Baker DI, Fugal P, Bradley EH, for the HELP Dissemination Project. Dissemination of the Hospital Elder Life Program: implementation, adaptation, and successes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10): 1492-1499. CriticalCareNurse Vol 32, No. 4, AUGUST 2012 25