Oklahoma`s Promise Scholarship Program

advertisement

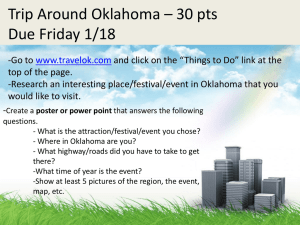

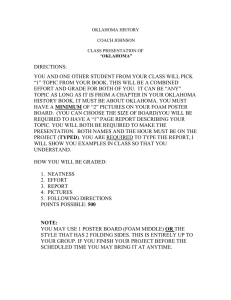

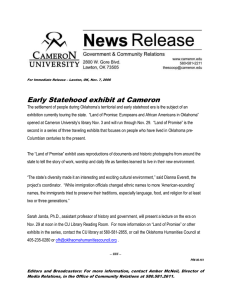

Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families ISSUE 3 Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program April 2013 BETTER BENEFITS FOR OKLAHOMA FAMILIES: ISSUE 3 April 2013 Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program CAP Tulsa produces Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families so that Oklahoma’s citizens, advocates and leaders can better understand how the State’s public benefit programs compare nationally in terms of program design, use, and funding. Each report includes recommendations to better serve the needs of Oklahoma children and their families. This report was written by Paul Shinn, Public Policy Analyst. The author thanks Liz Eccleston, Rebecca Fuhrman, Monica Barczak and Steven Dow at CAP Tulsa, Vickie Choitz at the Center for Law and Social Policy, David Blatt of the Oklahoma Policy Institute, David Castillo and Martha Vasquez of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, Melissa Neal and colleagues at Oklahoma College Access Program for program insight and review of earlier drafts and Bryce Fair, Carol Alexander and colleagues at the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education for insight, data and patient explanations. CAP Tulsa’s Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families series is available online at: http://captulsa.org/innovation-lab/public-policy/ For more information, please contact Paul Shinn, Public Policy Analyst, at pshinn@captulsa.org or (918)855-3638 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Introduction 5 Oklahoma’s College Graduate Imperative 6 What is Oklahoma’s Promise? 8 What Oklahoma’s Promise Should Be 9 Qualifying for Oklahoma’s Promise11 Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Benefits14 Student Performance in Oklahoma’s Promise 15 Boosting Low-Income College Graduation through Oklahoma’s Promise A Step-by-step Approach 17 STEP 1: High School: Accomplishment and Readiness 19 STEP 2: Choosing the Right College 21 STEP 3: Adequate Financing for College 23 STEP 4: Committing to College 25 Building a New Path to Low-Income College Graduation through a Promise Scholarship for Returning Adults 26 Putting it Together: A College Graduation Approach to Scholarships 28 Sources29 Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 3 Executive Summary The benefits of increasing college attainment for individuals and for society are well known. For individuals, college attainment is the single largest contributor to economic success and upward mobility. Oklahoma is behind the rest of the nation in increasing the share of adults with post-secondary degrees. Both in Oklahoma and the United States as a whole, low-income students lag behind in college completion rates. Oklahoma’s Promise, the state’s early intervention scholarship program for low- and middle-income students, helps address the gap in low-income educational attainment. Students who enroll in Oklahoma’s Promise and complete its academic and other requirements in high school, meet a second income test, and enroll in a qualifying Oklahoma college within three years of high school graduation may receive significant scholarship funding. The scholarship covers up to five years of tuition, but not fees and other costs of attending college. Oklahoma’s Promise has had impressive results for students who have enrolled and persisted through the program. Students who complete high school with the program requirements have had better high school and college grades and higher college enrollment, persistence, and graduation rates than other Oklahoma students. Thousands of Oklahoma youth have completed college, many of whom could not have done so without this program. However, Oklahoma’s Promise is not fully achieving its potential to increase individual and state educational attainment. Too many eligible students do not enroll in the program and too many students who do enroll either do not complete high school college-ready, do not enter college, or do not earn a degree. A careful analysis of the steps necessary for low-income students to graduate from college indicates Oklahoma’s Promise can be improved to increase graduation rates. Specifically, the program should: 1. Provide better financial and other supports to Oklahoma’s Promise students in high school by paying for Oklahoma’s Promise students to earn college credits in high school, take a college entrance test and acquire help to complete financial aid applications, requiring students to meet annually with a counselor and take a college entrance test, funding evidence-based non-financial supports in high school, and increasing enrollment of qualifying students by automatically enrolling students or allowing enrollment of qualified students through their senior year in high school. 2. Help students choose, afford, and persist in colleges where their chances of graduating are higher by better preparing high school counselors to guide low-income students to schools that meet their abilities, providing higher scholarships for attending full-time and continuously at colleges with high graduation rates, phasing out Oklahoma’s Promise eligibility for colleges with the lowest graduation rates, removing college grade requirements that hinder graduation, and requiring both students and colleges to better connect students with each other and with campus life. 3. Even with a more effective Oklahoma’s Promise program, though, the state won’t dramatically increase college graduation until it increases college attainment for adults as well as high school students. The state should establish a state-level scholarship based on Oklahoma’s Promise but geared to the special academic and personal challenges facing low-income adult students. 4 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Introduction As the world progresses from an industrial to an information-based economy, education needs are changing. Without at least some college or technical school, individuals face limited career and life choices and may fall behind their more-educated peers. Similarly, nations and states whose citizens cannot attain higher education levels risk being unable to compete for employers and could face lower incomes along with higher costs to support under-prepared citizens and communities. This report assesses Oklahoma’s Promise (OKP), the state’s early intervention college scholarship program, in the context of the need to increase college graduation rates. It begins by showing the benefits Oklahoma and its citizens will gain from increased college graduation rates. It describes the goals, program design, and outcomes for Oklahoma’s Promise. It then summarizes the essential steps to college success that have been identified by student-level research. It describes how effectively Oklahoma’s Promise supports students in taking each step and suggests ways Oklahoma’s Promise can more effectively increase college graduation rates, particularly for low-income students. Wherever possible, these suggestions are based on programs that have evidence of success. The report concludes with a restatement of recommendations that can improve Oklahoma’s Promise as a tool in the state’s drive to increase educational attainment. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) “...nations and states whose citizens cannot attain higher education levels risk being unable to compete for employers and could face lower incomes along with higher costs to support under-prepared citizens and communities.” Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 5 Oklahoma’s College Graduation Imperative College attainment is a key to success for individuals and an economic driver for states. Individual benefits to those who attain a higher education level include: • Higher incomes: In 2009, young adults with bachelor’s degrees earned $15,000 more annually than those with a high school diploma only ($45,000 vs. $30,000). The difference is greatest for minorities (National Center for Education Statistics 2011). In Oklahoma, college graduates earn more than double what high school graduates earn (Institute for Higher Education Policy 2005). • Higher employment: In 2009, Oklahoma adults with just a high school education were almost 3 times more likely to be unemployed than those with bachelor’s degrees. • Upward mobility: Children of low-income parents who finish college are likely to reach middle class status or higher, while “High school dropouts and high school graduates who do not attain postsecondary education are losing their middle-class status” (Carnevale and Strohl 2010: 71). Benefits to the state from increasing the percentage of Oklahomans with college degrees include: • A Stronger Economy: State economies thrive with higher educational attainment. A state’s economy grows by as much as 15% more for every 1 year increase in average educational attainment (Biswas et al. 2008). • Lower public costs: Nationally, adults with only a high school diploma are 4 times more likely to receive food stamps or cash welfare assistance than those with bachelor’s degrees (Nichols 2012). • Better civic outcomes: A range of studies finds that higher educational attainment results in lower crime rates, increased charitable giving, higher voting rates, and more volunteering (Institute for Higher Education Policy 2004, Prince and Choitz 2012). It is particularly important for both individuals and the state that college graduation rates increase for low- and middle-income people. First, low-income Oklahomans have the most to gain in terms of income and quality of life. Second, without significant increases in education, they are the most likely to face prolonged unemployment and need assistance. Third, educational attainment for higher-income Oklahomans is already fairly high; increasing the state’s overall graduation rates can only be accomplished by increasing those rates for lower-income students, both those attending directly from high school and adults returning to complete their education. 6 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org However, Oklahoma’s attainment lags behind the nation as a whole. Alarmingly, the gap between Oklahoma and national college attainment doubled from 1990 to 2009. In 2009 just 23% of Oklahomans had at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 28% of all Americans (U.S. Department of Commerce 2012). Each year, Oklahoma falls farther behind; 6-year graduation rates for Oklahoma students who entered 4-year colleges in 2003 were 10 percentage points below the national average. Associate degree attainment rates were even lower (U.S. Department of Education 2012a). The Center for Law and Social Policy (2012) estimates that in just 8 years, Oklahoma will need to nearly double the number of adults with at least an associate’s degree The Center for Law and Social Policy (2012) estimates that in just 8 years, Oklahoma will need to nearly double for the state to remain the number of adults with at least an associate’s degree for the state to remain economically competitive. This economically competitive. gap must be narrowed and eliminated if the state is to support upward mobility for citizens and build a stronger economy. Oklahoma’s Promise is part of a strategy to reduce the gap, but it must do more. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 7 What is Oklahoma’s Promise? Oklahoma’s Promise, formally known as the Oklahoma Higher Learning Access Program or OHLAP was created in 1992. OKP is one of several state-managed scholarship programs that states have developed in the past two decades. These scholarships differ from traditional financial aid by offering students more transparency, certainty, and actionable knowledge. Generally, these programs seek to reduce the impact of rising costs of attending college, promote preparation in high school, and achievement in college, save money on remedial courses, and encourage talented students to stay in state for college and work (Florida Postsecondary Education Planning Commission 1999). Three types of state scholarships are offered by at least 16 states: • Academic-based scholarships require students to achieve minimum high school grades to qualify for aid. • Income-based scholarships are offered based on income level of students and their families, though many also have minimum grade requirements. • Early intervention scholarships are income-based scholarships that require students to enroll several years prior to high school graduation. They have academic and other requirements that are designed to increase high school achievement and college readiness of participating students. Oklahoma’s Promise is one of three large state-funded early intervention voucher scholarships (Indiana and Washington have similar programs).1 Several other states and communities offer small early intervention voucher scholarship programs through federal GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs) grants. 1 8 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org What Oklahoma’s Promise Should be The legislation creating Oklahoma’s Promise (OKP) states two goals for the program. First, it is “…to provide an award to students who meet the criteria [for eligibility].” Second, it is to “…establish and maintain a variety of support services whereby a broader range of the general student population of this state will be prepared for success in postsecondary endeavors” (70 Oklahoma Statutes 2012 §2602). The program is thus designed to foster college access but not explicitly to increase low income students’ college graduation. The emphasis on enrollment, rather than completion, is reflected in Figure 1, which shows the history of enrollment and persistence through the various stages of Oklahoma’s Promise. Significant numbers of Oklahoma’s Promise students leave the program at every stage. The greatest drop comes during high school. Over one-third of class of 2012 enrollees failed to complete the OKP requirements in high school. Further, the number of OKP high school requirements completers has remained virtually the same for five straight years.2 The rate of attrition in high The rate of attrition in high school suggests that more than just the promise of a scholarship is needed to prepare many students for successful high school completion and transition in to college. Figure 1 Oklahoma's Promise Persistence, 2002-12 12,000 10,000 Enrolled 8,000 Completed High School Program Requirements Received Scholarship 6,000 4,000 Graduated w/in 6 Years 2,000 0 High School Class This figure shows that OK Promise application growth has slowed since 2008 and that high school completion and college attendance have been stable for 3-4 years. In the class of 2006, 69% of original applicants completed high school requirements, 57% attended college, and 23% graduated within 5 years. Source: CAPTulsa calculations from Oklahoma State Regents 2013a. Source: CAP calculations from Oklahoma State Regents 2013a. However, the majority of students who enroll in Oklahoma’s Promise do complete high school, with or without the program’s core course requirements. At least 82% of class of 2012 enrollees graduated from high school (Fair 2013). 2 Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 9 school suggests that more than just the promise of a scholarship is needed to prepare many students for successful high school completion and transition in to college. Attrition continues beyond high school as well. Even though OKP college graduation rates are high in comparison to other students, the loss of students before college graduation remains high—only half who enroll in college graduate in 6 years. In recent classes somewhat over 10,000 middle and high school students have enrolled in Oklahoma’s Promise each year. At current graduation rates, one can anticipate that no more than 3,000 of them will graduate from college each year well into the future. It is worth noting, however, that the recent 6-year graduation rates for Oklahoma’s Promise students, 45-50%, are equal to or somewhat higher than graduation rates typically calculated for low- and moderate-income students. To be an effective tool in Oklahoma’s quest for more college degrees, Oklahoma’s Promise’s goal should be redirected. Rather than enrollment and access, the program should be geared toward sucessful completion of both high school and college. The Legislature should set, and the Regents should strive to achieve, ambitious goals for the program to produce more low-income college graduates. Doubling the class of 2005’s 2,200 graduates should be the goal for more recent classes. This will require a new approach emphasizing persistence over enrollment, as described later in this report. 10 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Qualifying for Oklahoma’s Promise In order to receive an Oklahoma’s Promise scholarship, students must meet eligibility requirements, complete an application, fulfill the high school requirements and enroll in colleges. These requirements are discussed in detail below. ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS: Oklahoma’s Promise is open to students attending public or private high schools or being homeschooled, with family income from all sources not to exceed $50,000 at the time of enrollment. 3 Since the median income for families with children in Oklahoma is $49,942, half of Oklahoma families are under the income limit for Oklahoma’s Promise. Eligible students may apply for OKP in the 8th-10th grade, but no later than the summer after completing the 10th grade.4 Under a new alternative program, 17 Oklahoma City and Tulsa middle schools may submit student applications for free or reduced price school meals directly to the Regents, along with an OKP application. Approved school meal applications indicate incomes below 185% of the federal poverty limit; these students still must meet the OKP income limit to enroll in the program (Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2012b).5 HIGH SCHOOL REQUIREMENTS: Once enrolled in Oklahoma’s Promise, high school students must meet academic and behavioral requirements. Students are required to graduate from high school with a 2.5 overall grade point average (GPA) for all four years and a 2.5 GPA on 17 required courses that constitute a college preparatory curriculum (Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2012).6 COLLEGE REQUIREMENTS: Beginning with the high school class of 2012, Oklahoma’s Promise students must file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) with the U.S. Department of Education. If the FAFSA indicates family adjusted gross income of $100,000 or greater, the student cannot receive an Oklahoma’s Promise scholarship. Students also must still be Oklahoma residents and must be U.S. citizens or in the U.S. lawfully at the time they enroll in college. Students who meet these requirements may receive a scholarship equal to tuition at a public university. Students must enroll in a public or private 2- or 4-year Oklahoma college or in a career-technical center. Students must meet the college’s admission requirements and must apply for additional financial aid. Once in college, students must have a cumulative GPA of 2.0 or higher at the end of their first 2 years of college and a 2.5 cumulative GPA calculated only on courses taken after the completion of 60 college credit hours, as well as meet campus requirements for satisfactory progress. Students who have been adopted or are in custody of court-appointed guardians may be exempt from income requirements. 3 4 Home-schooled students are eligible and must enroll by their 16th birthday. Except for very large families or those with high amounts of nontaxable income, students at or below 185% of FPL will also meet OKP’s income limit. 5 Students who are home-schooled or attend non-accredited high schools also must achieve a composite ACT score of 22 or above to qualify for a scholarship. 6 Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 11 PROGRAM LIMITATIONS: Oklahoma’s Promise helps a small proportion—less than one in five—of the state’s low-income college students. Figure 2 compares students receiving OKP and other state income-based scholarships to students who receive Pell Grants (generally those with under $40,000 family income). The Pell Grant count is the best available estimate of the number of low-income students actually attending college. OKP reaches more low-income students than most other state income-based scholarships, but many other students in need do not receive scholarships. State Scholarships as % of Pell Grants Figure 2 Proportion of Low-Income Students Receiving State Scholarships State Scholarships as % of Pell Grants 40% 36% 32% 28% 24% 20% 16% 12% 8% 4% 0% Oklahoma Indiana Early Intervention Hawaii Mississippi Tennessee Senior-Year This chart shows showsOklahoma Oklahoma‘s'sPromise Promiseprovides providesfunds funds a larger proportion of low-income students toto a larger proportion of low-income students than any state state income-based income-basedprogram programexcept except Mississippi's. However, in five low-income Mississippi’s. However, lessless thanthan oneone in five low-income Oklahoma students receive an an Oklahoma’s Promise scholarship. Oklahoma's students receive Oklahoma's Promise scholarship. Scholarships awarded of of thethe state receiving PellPell Grants. Scholarships awardedas asaapercentage percentageofofresidents residents state receiving Grants. Source: CAP calculation reports Department of Education 2012. Source: CAPTulsa calculation fromfrom statestate reports andand U.S.U.S. Department of Education 2012. 12 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org The program’s design omits 2 key populations that need assistance if the state is to increase college attainment: • Eligible high school students who fail to enroll in OKP: Many low-income students who could succeed in college miss out on OKP aid because they did not complete an application. As shown in Table 1, about half of lower-income high school students apply to Oklahoma’s Promise. Failure to apply may result from lack of awareness, lack of family support, or low aspirations and expectations. As a result, thousands of young students with good chances of success may miss out on the opportunity to attend college. To most effectively serve these students, Oklahoma needs to encourage more qualified students to enroll in Oklahoma’s Promise. Two options to explore are automatically enrolling students and allowing enrollment of qualified students through their senior years in high school. • Adult students returning to college: States wanting to increase college attainment must support more than traditional college students, because the number of new high school graduates will not grow as fast as the need for high-skilled workers. (Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings 2012). The needs of adult students differ greatly from the traditional students OKP is designed to help. Adult students have less information about financial aid, are less likely to apply for aid, and have a lower likelihood of qualifying for and receiving aid. (Choitz and Strawn 2011). They also face additional costs of child care, transportation, and lost wages for time spent in school. Because they must balance work, family, and education, they may need longer to graduate than allowed under many financial aid programs (Biswas et al. 2008). Oklahoma’s adult students could benefit from a program like Oklahoma’s Promise that is tailored to the specific needs of adult students. Table 1. Comparative Takeup Rates for Early Intervention Scholarships Oklahoma Eligible students Indiana Washington 21,000 29,469 28,093 9,894 9,608 15,940 Application takeup rate 47% 33% 57% Completing high school with requirements 6,468 6,560 n/a Completer takeup rate 31% 22% n/a 5,296 1,960 n/a 25% 7% n/a Scholarship applicants Scholarships awarded Award takeup rate Source: Eligible students calculated by CAP Tulsa staff for Oklahoma and Indiana. Washington eligible students reported by program. Applicants, completers, and scholarships reported by programs. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 13 Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Benefits Oklahoma’s Promise students who complete the high school requirements may receive a scholarship once they apply for other financial aid and are admitted to a qualifying Oklahoma college. Students have up to three years after graduating from high school to claim the scholarship. Students may continue to receive benefits for up to five years or until they receive a Bachelor’s degree, whichever is shorter, provided they meet grade and other eligibility requirements discussed above. The amount a student receives depends on the school she attends and the number of hours enrolled. For state schools, the benefit is equal to the hourly charge for tuition (but not fees). This ranges from $1,770 to $4,440 per year for a full time student. Students attending private colleges receive a scholarship equal to tuition at a comparable state university. Oklahoma’s Promise scholarships are “last dollar,” meaning the award is reduced if all financial assistance exceeds the total cost of attendance defined under federal law (Oklahoma State Regents 2011, 70 Oklahoma Statutes §1604, Oklahoma Administrative Rules 610:25-23-7). In many cases OKP students receive additional financial aid to defer the significant costs of attending college: Even with full OKP, Pell, and OTAG aid, a student would still be left with $6,274 in unmet need, which the student would need to cover with limited outside scholarships, student loans, and/or income from work. • In 2010-11, Regents staff estimated that 79% of OKP freshmen recipients were eligible for a federal Pell Grant, which could pay up to $5,550 per year; it is not known how many of these students actually received Pell Grants. • In 2010-11, 27% of OK Promise students also received Oklahoma Tuition Aid Grants (OTAG) of up to $1,300 per year and 3% received up to $2,000 under the Oklahoma Tuition Equalization Grant (OTEG) to attend private colleges. • The University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University and several other colleges offer additional campus-based aid to Oklahoma’s Promise students. • Two Oklahoma community colleges offer assistance to students who successfully complete high school in their service areas. Like Oklahoma’s Promise, both programs serve new high school graduates but not adults returning to school. Some students exhaust this benefit and claim an OKP scholarship to help complete their studies. Even with full OKP, Pell, and OTAG aid, a student would receive $11,154 in aid to attend the University of Oklahoma, which estimates a total cost of $17,428 per year (Oklahoma State Regents 2011a, 2011b, University of Oklahoma 2012). This leaves the student with $6,274 in unmet need, which the student would need to cover with limited outside scholarships, student loans, and/or income from work. 14 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Student Performance in Oklahoma’s Promise This section shows how Oklahoma’s Promise students compare to other students in high school and in college performance. HIGH SCHOOL PERFORMANCE: Table 2 shows that Oklahoma’s Promise students who complete high school with the program requirements have better high school results than other students. High school grades and college-going rates of Oklahoma’s Promise completers are higher than for Oklahoma students as a whole, while ACT scores are similar. Some caution should be used in interpreting this data since only OKP completers are considered in the college-going rate and many noncompleters probably do not take the ACT. Table 2. Oklahoma’s Promise students who complete high school with the program requirements have better high school results than other students. High School Outcomes for Oklahoma’s Promise and All Students Indicator (and HS Class) Oklahoma’s Promise Completers All Students Difference Grade Point Average (2011) 3.39 3.0 13% Average ACT Score (2010) 20.9 20.9 0% College-going Rate (2009) 82% 51% 61% Note: Data are for different high school classes, as shown in parentheses. Oklahoma’s Promise data is for completers only, not all students who enroll initially. Source: Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2012a. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 15 COLLEGE PERFORMANCE: Figure 3 indicates that OKP students who persist through the program and attend college generally have better outcomes than other Oklahoma college students. OKP students are much more likely to persist from their freshman to sophomore year and to graduate within 6 years. They also require somewhat fewer remedial courses, which is a positive output since remedial education often delays or derails college completion altogether (Complete College America 2012). Oklahoma’s Promise students’ relative college success, however, should be considered in context. While OKP students do better than others, a significant number still fail to complete college. Barely over half of those who return for a second year end up graduating in 6 years or less. As long as persistence and graduation levels remain at their current rates, both for OKP and all students, the state will not make significant progress in overall college graduation and low-income students will continue to face limited life opportunities. Figure 3 College Outcomes for Oklahoma's Promise and All Students 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% Oklahoma's Promise 0% % in Remedial % with % Persisting to % Enrolled Full- % Completing % Graduates Courses Freshman GPA Sophomore time Degree in 6 Employed in OK 2.0 or Higher Year Years Other Students This figure shows Oklahoma's Promise students perform slightly better in all aspects of college attainment and completion, including need for remediation, grades, full -time status, persistence, graduation, and post-graduate employment. Data for 2009 except 6-year graduation rate, which is for high school class of 2005. Employment compares to other Oklahoma resident students only. Source: Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2012. By law, Oklahoma’s Promise funding is reserved each year based on the Regents’ estimate of program cost. For the 2012-13 academic year $57 million in state income taxes was reserved for OKP (Oklahoma Office of State Finance 2011). In part because of Oklahoma’s Promise, Oklahoma fares well in college financial aid, particularly need-based aid, among the states. The National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs (2012) reports Oklahoma ranks 21st among states in total state financial aid per full-time undergraduate student and 12th in need-based aid per full time student. 16 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Boosting Low-Income College Graduation through Oklahoma’s Promise – a Step-by-Step Approach In spite of Oklahoma’s Promise, Oklahoma’s graduation rates, particularly for low-income students, are comparatively low. Figure 4 shows that graduation rates for Oklahoma students at 4-year schools who receive Pell Grants are lower than those of Pell students in other states and lower than graduation rates for all Oklahoma students. At 2-year schools, Oklahoma lowincome students do better than those in other states or their higher-income peers. This is a solid base to build on, but the 2-year graduation rate for Pell students is too low. Figure 4 % Graduating in 150% of Expected Time Graduation Rates by School Type and Income 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% OK Pell 10% U.S. Pell 0% 4 year 2 year OK All Students College Type This graph shows Oklahoma 4-year college students with Pell grants graduate at lower rates than Pell students nationwide and Oklahoma students as a whole. Oklahoma Pell students at 2-year colleges have higher graduation rates than other Okllahoma Oklahoma students and other Pell students, though rates remain low. Source: Complete College America 2010. Oklahoma is undertaking ambitious reforms to increase overall college graduation rates. The Common Core Curriculum and other reforms in secondary school are designed to increase college readiness for high school graduates. The Regents have incorporated graduation rates into funding for campuses, are restructuring remedial courses, and are participating in the multi-state Complete College America initiative. This section suggests how Oklahoma’s Promise can be a more effective part of an overall strategy to increase graduation rates. Research across the nation has identified four key steps in a successful college career that leads to graduation. The box on the following page shows the key indicators that define the importance of these steps. Each of these steps is discussed below; describing how Oklahoma’s Promise is helping, identifying evidence-based and promising programs that are helping students do even better, and suggesting ways Oklahoma’s Promise can be improved by adopting new graduation-oriented strategies. The report then concludes with a summary of the recommendations identified in this section. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 17 STEP 1: HIGH SCHOOL: ACCOMPLISHMENT AND READINESS: Several aspects of high school experience have powerful impacts on college graduation: • Every year Oklahoma has over 14,000 income-eligible students who do not qualify for OKP because they did not enroll or did not complete high school with the required grades. • Academic preparation in high school has a significant impact on college graduation. Completing a high “standard of content” in high school had a greater impact on college graduation than race, gender, socioeconomic status, or high school grades. This link is most powerfully represented in mathematics courses. Most recently, a study of 2004 high school graduates shows students who completed at least algebra II or trigonometry were 40% more likely to complete college, adjusting for all other factors. Students who earn college credits in high school are 39% more likely to receive a college degree (National Center for Education Statistics 2012). • College success also depends on how a student prepares for college outside the high school classroom. Students who take the ACT or SAT college entrance examinations are 52% more likely to graduate with an associate’s or bachelor’s degree than those who do not (National Center for Education Statistics 2012). However, much of the SAT score depends not on a student’s abilities, but on her background. One way to improve college access for lowincome students is for more to enroll in test preparation courses (Carnevale and Strohl 2010). A longitudinal study in Austin, Texas showed that meeting with a counselor to discuss college and completing a FAFSA both increased the rate of college enrollment for all students; FAFSA completion had higher impacts for the lowest-income students and for first-generation college students. This study did not address college graduation impacts (King 2012). STEP 2: CHOOSING THE RIGHT COLLEGE: Longitudinal research suggests college choice has a significant impact on chances for graduation and that lower-income students often make choices that reduce their graduation—and career—prospects: • Initially attending a four-year college is the single largest predictor of college graduation rates; one national longitudinal study found that starting at a four-year college increased the odds of graduating with either an associate’s or bachelor’s degree by 62% after adjusting for all other factors (National Center for Education Statistics 2012). Only one in twenty low-income, first generation students who starts at a two-year college completes a bachelor’s (Engle and Tinto 2008). • Attending a more selective college increases chances of graduation and lifetime economic success. Nationally, the 18 most competitive four-year schools have a graduation rate that is more than twice that of noncompetitive schools. Among those who do graduate, entry level earnings are $17,000 higher for graduates of highly competitive colleges than those of the least competitive 4-year schools (Carnevale and Strohl 2010). • Low-income students are less likely to attend four-year and more competitive colleges, regardless of academic preparation. Less than half of the highest-scoring students with low incomes attend a four-year college, compared to more than three quarters of high-scoring, high-income students (Carnevale and Strohl 2010). Low-income students tend to “under match”—attend a college below their level of academic capability—because they do not plan early for college, do not have access to resources and information about college, underestimate financial aid resources while overestimating costs, and limit their college choices geographically (Institute for Higher Education Policy 2012). Education Policy 2006). In 2004-05, full-time students in the lowest one-fourth of family incomes faced a net price after financial aid of $7,300 per year (National Center for Education Statistics 2011a). STEP 4: COMMITTING TO COLLEGE: Once in college, students are most likely to stay on track if they are full-time, enroll continuously, and connect on a personal level with their campus • Figure 5 shows that full-time attendance makes a significant impact on graduation prospects for Oklahoma students. In Oklahoma, just 25% of students who attend 4-year colleges part time graduate in 8 years, compared to 56% who attend full time. At 2-year colleges, 12% of part-time students graduate in 4 years compared to 22% of full-time students (Complete College America 2010). • New Oklahoma’s Promise college grade requirements being implemented for the 2012 college freshmen class and each entering freshmen class thereafter could possibly cut graduation rates significantly. Regents staff indicates that the grade requirement for the last 60 hours is difficult to explain to students and may eliminate the award for 18% of OKP college juniors and seniors who would otherwise be on track to earn a degree (Fair 2012). STEP 3: ADEQUATE FINANCING FOR COLLEGE: Income is a significant barrier to college success and the gap between high- and low-income students is persistent. There is some evidence that financial aid closes this gap. • Students from families in the lowest one-fourth by income are half as likely to graduate with an associate’s or bachelor’s degree as those in the highest one-fourth of incomes. Even the next income group (those from the 25th to 50th income percentile, who are also served by Oklahoma’s Promise) is less likely to graduate (National Center for Education Statistics 2012). • Students who “stop out”—leave school for one or more semester—are 60% less likely to graduate with any degree. • Students who ever attend college part-time are 52% less likely to graduate with any degree. • Students who participate in college clubs their freshman year are 39% more likely to graduate. • Income is a more powerful factor in graduation than ability. While 74% of high-income students who score well on achievement tests finish college, only 29% of low-income students with the same scores finish (Deming and Dynarski 2009). • Inadequate aid works in several ways to reduce graduation rate for low-income students. Since many first-generation, low-income students have substantial unmet financial needs, they are more likely to live off campus, work long hours, and be part-time students, all of which reduces their chances of graduating. After financial aid, students who are low-income, first-generation, or both, have higher unmet needs than their 60% higher-income peers. Increased 50% aid for these students has been 40% shown to increase college 30% persistence (Engle and Tinto 20% 2008). • Changes in federal and state aid policies around the nation have hurt low-income students. In 2004-05, federal Pell Grants paid only one-third of the cost of attending a 4-year public institution (Institute for Higher % Graduating in 200% of Expected Time KEY INDICATORS FOR FOUR STEPS TO COLLEGE GRADUATION • Students who meet with an advisor their freshman year are 30% more likely to graduate (National Center for Education Statistics 2012). • More students who are either low-income or firstgeneration college students attend part-time, compared to their peers, and fewer are engaged in campus academic and social activities, often due to work and family demands (Engle and Tinto 2008). Figure 5 Oklahoma College Graduation Rate by College Type and Attendance 10% Full time 0% 4 year 2 year Part time This figure shows that full-time students are more than twice as likely to graduate from 4-year colleges in 8 years and from 2-year colleges in 4 years than students who attend part -time. Source: Complete College America 2010. Community Action Project www.captulsa.org STEP 1: HIGH SCHOOL: ACCOMPLISHMENT AND READINESS: To a great extent, college success is determined by actions students and their families take in high school. How Oklahoma’s Promise helps: Oklahoma’s Promise requires students to complete an intensive high school curriculum, thus better preparing them for rigorous college material. OKP’s curriculum requires students to complete 3 math courses, including geometry and algebra II. Other subject requirements are consistent with the intensive curriculum that has been shown to increase college graduation rates. It requires OKP students who plan to attend to complete the FAFSA. However, Oklahoma’s Promise does not require or encourage students to earn college credits in high school, attend test preparation courses, take college entrance examinations, or meet with counselors. Programs that work: Studies of early intervention programs have found that a combination of scholarships and support for students and families is more effective in promoting successful high school completion than either scholarships or support alone. Successful programs combined scholarships with ongoing contact between students and their families and effective use of peer groups (Cunningham et al. 2003). Several studies have identified high school strategies to increase the number of college-ready high school graduates.7 • Administering college readiness assessments in the 10th or 11th grade helps students address deficiencies before arriving at college; California, Texas and Virginia all practice this strategy and reduce remedial needs in college (Complete College America 2012, Education Commission on the States 2012). Oklahoma offers students the opportunity to participate in the ACT ladder of college readiness assessments in 8th and 10th grades (Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2013). • FAFSA assistance can be a key to college access. Students who complete the FAFSA are more likely to enroll, but the process is highly intimidating (Brown Center for Education at Brookings 2012). A program that used tax preparers to assist families in completing the FAFSA had dramatic impacts for both traditional and adult students on FAFSA completion, the amount of aid received, and college enrollment rates (Bettenger et al. 2009). • Indiana’s early intervention scholarship program includes mentoring, tutoring, parent involvement requirements, service learning, career counseling, and campus visits along with a voucher scholarship. An evaluation indicated the program increased initial and continuous college enrollment (Cunningham et al. 2003). • The College Summit program enlists entire schools that serve high proportions of disadvantaged students. The program consists of a 4-week summer program for student leaders, an intensive 12th grade curriculum, and professional development for counselors and other school staff. This program increased college enrollment for low-income students, particularly in schools with high participation rates (Ironbridge Systems 2010). Unfortunately, no studies have examined the impact of high school interventions such as these on college graduation, concentrating on enrollment and persistence instead. 7 Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 19 How Oklahoma’s Promise can do better: Oklahoma’s Promise encourages students to prepare for college success in the high school classroom, but offers few supports outside the classroom. While academics are one reason that low-income students do not attend and succeed in college, they are not the only reason. Oklahoma’s Promise should provide supports outside the classroom as well. These are relatively low-cost supports that put minimal burdens on students, families, and high school staff. Oklahoma’s Promise can support higher college graduation rates among low-income students by: • funding tuition and other costs for students who enroll in college courses while in high school. Oklahoma law requires colleges to waive tuition to high school seniors taking concurrent enrollment courses at Oklahoma public colleges, but the student is responsible for fees, books, and other costs. Oklahoma’s Promise could greatly enhance this opportunity by paying for costs in addition to tuition and by automatically enrolling OKP students for the waiver. • providing funding for students to complete a college entrance test (ACT or SAT) preparation course and require them to take at least one entrance test, • providing funding to help enrolled students complete the FAFSA, • requiring enrolled students meet annually with a counselor to discuss college plans, • funding schools and community organizations that develop evidence-based support programs, and • creating alternative paths to enrollment, potentially including automatic enrollment for 10th graders likely to meet program requirements or enrolling students who did not enroll by 10th grade but otherwise demonstrated readiness for college to enroll and earn a scholarship as late as their senior year of high school. These supports can be most effective if offered to all students who enroll in Oklahoma’s Promise, whether or not they are on track to meet the program requirements. 20 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org STEP 2: CHOOSING THE RIGHT COLLEGE: Whether a student graduates with either a 2- or 4-year degree is highly dependent on the college the student first attends. Oklahoma’s Promise does not restrict college choices for students who qualify for a scholarship. How Oklahoma’s Promise helps: Oklahoma’s Promise does not explicitly influence students’ college choice, but it does move students toward colleges with higher graduation rates. Figure 6 shows that Oklahoma’s Promise students are more likely to attend 4-year schools than Oklahoma students as a whole. Within 4-year schools, more OKP students attend colleges with high and medium graduation rates. In 2-year schools, Oklahoma’s Promise students are less likely than all students to attend low-graduation colleges. However, many Oklahoma’s Promise students still attend colleges with low graduation rates.8 Figure 6 Proportion Attending College by Graduation Rate, Oklahoma's Promise and All Students, 2009-10 0.4 % of Students Attending 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 OK's Promise 0 4 year highest 4 year middle 4 year lowest 2 year highest 2 year middle 2 year lowest All Students 4- and 2-year Colleges Grouped from Highest to Lowest Graduation Rate This graph shows that Oklahoma's Promise students are more likely than other students to attend 4-year colleges and those with the highest graduation rates. However, 25% of OK's Promise students attend 4- or 2-year schools with the lowest graduation rates. Source: Chronicle of Higher Education 2012, Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education 2010, 2012a. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education (2012), only 8 of Oklahoma’s 53 colleges reporting data have 3- or 6-year graduation rates of 40% or higher. These include the two public research universities, five private non-profit four-year colleges (University of Tulsa, Oral Roberts University, Oklahoma City University, Oklahoma Baptist University, and Southern Nazarene University, and one private for-profit fouryear college (Spartan College of Aeronautics). 8 Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 21 Oklahoma’s Promise’s design helps explain why its students attend schools with higher graduation rates. The high school curriculum requirement helps prepare students for more selective colleges. The scholarship is tied to tuition rather than a fixed amount, so it may help students attend more expensive colleges. Programs that work: Few programs have been proven to shift low-income students to colleges that are more selective and have higher graduation rates. There is some evidence that the Federal Upward Bound program, which provides comprehensive precollege services including college-prep courses, exposure to college campuses, mentoring, and counseling, moves students from 2- to 4-year colleges (Deming and Dynarski 2009). Generally, experts agree on several key elements of a strategy to improve graduation rates for low-income students (Carnevale and Strohl 2010, Deming and Dynarski 2009, Engle and Tinto 2008, King 2012). • Engage students and their families early in high school to plan for college. • Increase financial aid by assisting with the FAFSA and building financial literacy. • Provide high school counselors with professional development so they better understand options and resources available to low-income students and use data to track student progress toward college. • Educate students and their families about the benefits of attending a 4-year college. • Encourage and help students apply for several colleges that align with their academic readiness • Shift resources to colleges and aid programs that benefit low-income students. Less-selective colleges and 2-year colleges have weaker results in part because they have fewer resources. Similarly, federal and state financial aid is increasingly tilted toward middle- and upper income students. How Oklahoma’s Promise can do better: For the state to most effectively leverage its investment in education, it must shift low-income students who qualify academically to more competitive schools. Recommendations previously discussed in step 1 can better prepare students to qualify for and access colleges with higher graduation rates. The Regents should take several additional steps to shift more students to higher-graduation schools. • Provide professional development for counselors and administrators at high schools who serve many OKP and other low-income students. Oklahoma’s Promise staff regularly provides information sessions for counselors; these could be broadened to better prepare counselors to use data to track student progress and help identify appropriate college options, provide students with assistance in the college search and application process, and assist students in securing financial aid. • Provide financial incentives for students who attend colleges with high graduation rates, as discussed in step 3, below. • Gradually eliminate Oklahoma’s Promise eligibility for low-graduation-rate colleges. Such a plan should be phased in so that no current OKP students attending any college are affected and so that current high school seniors’ college choices are not affected. 22 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org STEP 3: ADEQUATE FINANCING FOR COLLEGE: Family income plays an integral part in student’s ability to prepare for, access, and complete college. How Oklahoma’s Promise helps: Oklahoma’s Promise is one of the most aggressive and successful efforts by any state to equalize college access and success for low-income students. It is available to more low- and moderate-income students than other state scholarship programs because it has a higher maximum income limit. Figure 7 shows OKP has higher income limits than other early intervention and income-based scholarships. Oklahoma’s income limits allow more moderate-income students to participate and increase the chances that more students will access and graduate from college. Figure 7 Maximum Income for Income-Based Voucher Scholarships $60,000 $50,000 $40,000 $30,000 $20,000 $10,000 $OK IN* WA* Early Intervention Scholarships HI* TN Senior-Year Scholarships This figure shows that Oklahoma's Promise has generally higher maximum limits than other early intervention and income-based state voucher scholarships. * Indicates maximum is 185% of Federal Poverty Level. Income shown is for family of 3. Excludes scholarships with small number of recipients and complex income calculations. Programs that work: Clearly, aid-based scholarships work, in the sense that they make a difference for many low-income students. There is also evidence that aid increases college enrollment and graduation of recipients. Several studies indicate that an increase in aid or reduction in tuition of $1,000 increases enrollment of eligible students by 4 percentage points. Further, merit-based state scholarships in Arkansas, Georgia, and West Virginia increased degree completion rates for participating students by 3-4 percentage points (Deming and Dynarski 2009). How Oklahoma’s Promise can do better: Figure 8 shows that Oklahoma lags behind other state scholarship programs in the proportion of student costs that it pays. For a student at the University of Oklahoma, OKP pays about half of combined tuition and fees, because fees are nearly as high as tuition. Across all colleges with high OKP enrollment, tuition averages three-fourths of the combined cost of Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 23 tuition and fees. In part as a result, Oklahoma’s Promise ranks well below Indiana and Washington early intervention scholarships and below the median level for other state income-based scholarships in share of costs it covers. Indeed, Oklahoma’s Promise pays students less than even the median academicbased state scholarship, which are offered to students at all income levels. More important for students and their families, OKP pays a lower percentage of total cost of attendance (including books, room and board, transportation, and incidentals) than other state scholarship programs. Oklahoma’s Promise pays less than a quarter of the full cost of attending the University of Oklahoma. The other early intervention scholarships pay up to half of the costs of attending a comparable university, while the median senioryear income based scholarship pays one-third. If Oklahoma’s Promise paid both tuition and fees, it would pay nearly half of the cost of attendance and would be competitive with the Indiana and Washington programs. Figure 8 100% Maximum Award as % of College Costs 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% Oklahoma 30% Indiana 20% Washington 10% Income-based (median) 0% As % of Tuition and Fees As % of Total Cost Academic-based (median) This figure shows how much of costs (tution and fees only as well as estimated total cost) paid by the maximum award under a voucher scholarship. Oklahoma's Promise pays both a smaller portion of tuition and fees and total costs than other voucher scholarships. Source: CAP Tulsa calculationsfrom fromstate state reports and research university cost estimates. Source: CAP calculations reports and research university cost estimates. In order to help students attend and complete the college best fitting their academic skills and to increase their chances of graduating, Oklahoma’s Promise scholarships should be increased to include both tuition and fees at colleges with the highest graduation rates. CAP Tulsa recommends that this increase be limited to 4-year colleges in the top half of the state by graduation rate and 2-year colleges in the top quarter by graduation rate. Oklahoma can also simplify and broaden the availability of financial aid by conforming OK’s Promise eligibility (other than income) as closely as possible to Pell Grant eligibility and updating eligibility rules as Pell Grants and other forms of aid evolve. 24 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org STEP 4: COMMITTING TO COLLEGE: Getting through college is harder than getting to college. Graduation requires students to commit time and energy and to connect with their colleges on an ongoing basis. How Oklahoma’s Promise helps: College persistence and graduation rates for Oklahoma’s Promise, which are higher than those of other Oklahoma students regardless of income, suggest the program is effective in increasing graduation rates. OKP is more likely to keep students in school than other financial aid because the student does not need to re-apply each year, the amount of aid increases as tuition increases, the amount of aid does not change if the student’s income or family circumstances change during college, and aid may last five years, where four is common in many state scholarship programs. Further, the program discourages part-time attendance and stop-outs by limiting aid to five calendar years in all circumstances. However, neither the Regents nor colleges offer specific non-financial assistance to OKP students once they start college. Programs that work: Few college-level support programs have been shown to increase college graduation rates. As in high school, however, one analysis of several programs concluded that financial aid combined with student services is more effective than either financial aid or student supports alone (Deming and Dynarski 2009). How Oklahoma’s Promise can do better: Oklahoma’s Promise can promote graduation for students already in college by adjusting financial incentives, by simplifying grade requirements, by encouraging student engagement on campus, and by incorporating student supports that are considered the best current practice. • Oklahoma’s Promise should further encourage full-time and continuous attendance through minor changes in financial incentives. Students should only receive the recommended scholarship increase discussed in step 3 if they are enrolled full-time and enrolled continuously. • Oklahoma’s Promise should eliminate the separate grade requirement for the last 60 semesters. Instead, students should be required to meet minimum grades and requirements for satisfactory progress that apply to all students on each campus. • Oklahoma’s Promise should encourage student engagement on campus to help increase participant graduation rates. Students should be required to meet with an advisor annually to maintain their scholarships. • For a relatively small additional investment, Oklahoma’s Promise can offer additional nonfinancial student supports to participants in college. OKP should encourage colleges to provide evidence-based counseling, mentoring, and academic support programs to OKP students. Campuses with sufficient numbers of OKP participants should establish learning communities and orientation courses for participants. Oklahoma’s Promise should require colleges to monitor and report on student progress and funding for supports should be based in part on successful OKP student outcomes. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 25 Building a New Path to Low-Income College Graduation through a Promise Scholarship for Returning Adults Oklahoma cannot meet the demand for college graduates solely by improving the path from high school straight through college. • Oklahoma has approximately 10 times as many 25-34 year olds with less than a bachelor’s degree than it graduates from high school each year. To improve its college • “Non-traditional” students are rapidly becoming the norm on campuses across the nation. More than one-third each of all college students are over age 24 or attend part-time (Brown Center on Educational Policy at Brookings 2012). graduation rates, the state • Nearly half of working-poor adults who attend college leave without a certificate or degree in 6 years (McSwain and Davis 2007). adults through college. needs a program to get more How Oklahoma’s Promise helps: Oklahoma’s Promise helps few students who do not proceed straight from high school to college and does not help adult students due to the 10th grade enrollment requirement. However, it does offer a model on which to base an adult promise scholarship model. Programs that work: Several promising programs across the country are demonstrating that financial assistance and student support can help adults return to and complete college. • Opening Doors, a long-term experiment at several community colleges across the country has had promising impacts on low-income student retention and performance. This performancebased scholarship program distributes funding in small amounts during the semester based on student performance. Campuses provide additional supports that may include mentoring, learning communities in which cohorts of students attend multiple classes together, and orientation classes. Results vary by campus and are preliminary, but some campuses have shown measurable increases in the number of courses taken, grades, and student persistence (Patel and Richburg-Hayes 2012). • Adult-oriented programs such as Kentucky’s Ready-to-Work Initiative and Washington’s Opportunity grants provide 2-year colleges with funds for low-income student counseling, tutoring, textbooks, and services like emergency assistance for transportation and child care. These programs have resulted in better college retention and graduation than for low-income students at the same schools who are not participating in the programs (Choitz 2010, Biswas et al. 2008). • Washington’s I-BEST program for adult technical education uses cohort approaches in which students take multiple classes together. Studies show this program increases the number of credits and certificates earned by students (Bailey and Cho 2012). How Oklahoma can do better: To improve its college graduation rates, the state needs a program to get more adults through college. The state should create an adult promise scholarship that incorporates the best elements of Oklahoma’s Promise, including simple income requirements, aid amounts that are known to students before they enroll, and aid that can be used at any qualifying Oklahoma institution. However, the program also must consider that adult students face different challenges and need different supports. These can be addressed by setting scholarship amounts high enough to cover tuition, fees, books, and other costs and by packaging all aid, including OTAG grants for adults, into a single, simple award. The program should include funding to colleges that serve adult promise students so they 26 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org can provide child care assistance, mentoring, tutoring, financial aid counseling and support, cohort enrollment approaches, and learning communities that low-income adult students need to succeed. Funding and supports should encourage students to attend as closely to full-time as possible, since part-time attendance is the single greatest predictor of failure for adult students (Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance 2012). Because this program will be a significant innovation for the state and because evidence is still being gathered on effective adult scholarship programs, Oklahoma’s new adult promise program should be piloted at one or more 2- and 4-year campues and evaluated before being implemented statewide. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 27 Putting it Together: A College Graduation Approach to Scholarships The previous sections describe the steps it takes to successfully graduate from college, the barriers that get in the way, and how Oklahoma’s Promise—and a new adult promise scholarship—can be improved to graduate more low-income students from Oklahoma colleges. This section summarizes the key improvements described previously: 1. Provide better financial and other supports to Oklahoma’s Promise students in high school by paying for Oklahoma’s Promise students to earn college credit in high school, to take a college entrance test and get help completing the FAFSA, by requiring students to meet annually with a counselor and take a college admissions test, by funding evidence-based non-financial supports in high school, and by automatically enrolling students or allowing enrollment of qualified students through their senior years in high school. 2. Help students choose, afford, and persist in colleges where their chances of graduating are higher by better preparing high school counselors to guide low-income students to schools that meet their abilities, providing higher scholarships for attending full-time and continuously at colleges with high graduation rates, phasing out Oklahoma’s Promise eligibility for colleges with the lowest graduation rates, removing college grade requirements that hinder graduation, and requiring both students and colleges to better connect students with each other and with campus life. 3. Help more low-income adult students enroll and succeed in college with a state-level scholarship based on Oklahoma’s Promise but geared to the special academic and personal challenges facing low-income adult students. 28 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Sources Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. 2012. Pathways to Success: Integrating Learning with Life and Work to Increase National College Completion. A Report to the U.S. Congress and Secretary of Education (Washington); available at http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/acsfa/ptsreport2.pdf. Bailey, Thomas, and Sung-Woo Cho. 2012. Developmental Education in Community Colleges. October. New York: Community College Research Center; available at https://mail.captc.org/owa/redir.aspx?C=rjPEX9V gtkqm2NktoczQrc0mwyk_lc9IatD5olRR6ail8dX1RCFBmsQb4qjKwG2K6_X16b2D91M.&URL=http%3a%2f%2fwww2. ed.gov%2fPDFDocs%2fcollege-completion%2f07-developmental-education-in-community-colleges.pdf. Bettenger, Eric, Bridget Terry Long, Phillip Oreopoulos, and Lisa Sanbonmatsu. 2009. The Role of Simplification and Information in College Decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA Experiment (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research); available at http://gseacademic.harvard.edu/~longbr/Bettinger_Long_ Oreopoulos_Sanbonmatsu_-_FAFSA_experiment_9-09.pdf. Biswas, Radha Roy, Vickie Choitz, and Heath Prince. 2008. Pushing the Envelope: State Policy Innovations in Financing Postsecondary Education for Workers Who Study. Breaking Through: Helping Low-Skilled Adults Enter and Succeed in College and Careers (Boston: Jobs for the Future); available at http://www.jff.org/ sites/default/files/BTPushingEnvelope.pdf. Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings. 2012. Beyond Need and Merit: Strengthening State Grant Programs; available at http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2012/05/08-grants-chingos-whitehurst. Carnevale, Anthony P. and Jeff Strohl. 2010. How Increasing College Access is Increasing Inequality and What to Do About It; chapter 3 in Rewarding Strivers, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press): 71-190; available at http://tcf.org/publications/2010/9/how-increasing-college-access-is-increasing-inequalityand-what-to-do-about-it/get_pdf. Center for Law and Social Policy. 2012. Return on Investment to Increasing Postsecondary Credential Attainment in Oklahoma. Accessed June 21, 2012 at http://www.clasp.org/resources_and_publications/publication? id=1465&list=publications_states. Choitz, Vickie. 2010. Getting what we Pay for: State Community College Funding Strategies that Benefit Low-Income, Lower-Skilled Workers (Washington: Center for Law and Social Policy, November); available at http://www.clasp.org/admin/site/publications/files/Getting-What-We-Pay-For.pdf. Choitz, Vickie and Julie Strawn. 2011. Testimony for the Record. Hearing on Nontraditional Students, Advisory Committee on Financial Assistance (November 3); available at http://www.clasp.org/admin/site/publications/files/ CLASP-testimony-on-nontraditional-students-to-ACSFA.pdf. Complete College America. 2010. Time is the Enemy: The Surprising Truth About Why Today’s College Students Aren’t Graduating…and What Needs to Change ( Washington); available at http://www. completecollege.org/docs/Time_Is_the_Enemy_Grad.pdf. _______. 2012. Remediation: Higher Education’s Bridge to Nowhere; available at http://www.completecollege. org/docs/CCA-Remediation-final.pdf. Chronicle of Higher Education. 2012. College Completion: Who Graduates from College, Who Doesn’t and Why it Matters; accessed December 18, 2012 at http://collegecompletion.chronicle.com/ state/#state=ok&sector=public_four. Cunningham, Alisa, Christina Redmond, and Jamie Merisotis. 2003. Investing Early: Intervention Programs in Selected U.S. States. Does Money Matter? Millennium Research Series Number 2 (Montreal: Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation); available at http://www.ihep.org/assets/files/publications/g-l/InvestingEarly.pdf. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 29 Deming, David and Susan Dynarski. 2009. Into College, Out of Poverty? Policies to Increase the Postsecondary Attainment of the Poor. Working Paper 15387 (September). (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research); available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/21761910/Into-College-Out-of-Poverty-Policies-toIncrease-the-Postsecondary-Attainment-of-the-Poor. Engle, Jennifer and Vincent Tinto. 2008. Moving Beyond Access: College Success for Low-Income, First Generation College Students (Washington: The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education); available at http://www.pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Moving_Beyond_Access_2008.pdf. Fair, Bryce. 2012. Electronic Communication with the Author (September 13). Florida Postsecondary Education Planning Commission. 1999. Florida’s Bright Futures Scholarship Program; a Baseline Evaluation; available at http://www.cepri.state.fl.us/pdf/bffin.pdf. Institute for Higher Education Policy. 2004. Investing in America’s Future: Why Student Aid Pays off for Society and Individuals; available at http://www.ihep.org/Publications/publications-detail.cfm?id=40. _______. 2005. The Investment Payoff: A 50-State Analysis of the Public and Private Benefits of Higher Education (Washington); available at http://www.ihep.org/assets/files/publications/g-l/InvestmentPayoff.pdf. _______. 2012. Maximizing the College Choice Process to Increase Fit and Match for Underserved Students. Research to Practice Brief (Winter); available at http://knowledgecenter.completionbydesign.org/sites/ default/files/321%20Pathways%20to%20College%20Network%202012.pdf. Ironbridge Systems. 2010. An Evaluation of College Summit Outcomes; Class of 2008; available at http://www. google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CDoQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww. socialimpactexchange.org%2Fsites%2Fwww.socialimpactexchange.org%2Ffiles%2FEvaluation.pdf&ei=yZnQUPDlHqHV0gH zvYGIBQ&usg=AFQjCNEFy4AQ4YkOljDgs-Zn7YWsw77eMg&bvm=bv.1355534169,d.dmQ. King, Chris T. 2012. Actions to Increase Direct-to-College Enrollment Rates. Ray Marshall Center Central Texas Student Futures Project (October). McSwain, Courtney and Ryan Davis. 2007. College Access for the Working Poor: Overcoming Burdens to Succeed in Higher Education. Institute for Higher Education Policy; available at http://www.google.com/url?sa=t& rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CDUQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cpec.ca.gov%2FComp leteReports%2FExternalDocuments%2FCollege_Access_for_the_Working_Poor_2007_Report.pdf&ei=cMrUUPz2EIPfrAG61I HAAQ&usg=AFQjCNF9kNzPWq_2E0GXnmpCSQgiO-I6jQ&bvm=bv.1355534169,d.aWM. National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. 2012. 42nd Annual Survey Report on StateSponsored Student Aid, 2010-11 Academic Year; available at http://www.nassgap.org/viewrepository. aspx?categoryID=3# . National Center for Education Statistics. 2011. The Condition of Education 2011. NCES 2011-033; available at http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=the%20condition%20of%20education%202011&source=web&cd= 2&ved=0CFgQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fnces.ed.gov%2Fpubs2011%2F2011033.pdf&ei=1_C_T7GdOY-J2AXO0tyDQ&usg=AFQjCNFoZoLbjtdot_j-hTVoghtCaq9t2A . _______. 2011a. Trends in Student Financing of Undergraduate Education: Selected Years, 1995-96 to 2007-08. Web Tables. NCES 2011-218; available at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011218.pdf#page=57. ______. 2012. Higher Education: Gaps in Access and Persistence Study: Statistical Analysis Report; available at http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CDUQFjAA&url =http%3A%2F%2Fnces.ed.gov%2Fpubs2012%2F2012046.pdf&ei=HF_PUKGWB4WLqgHL5oHwBQ&usg=AFQjCNEwBfsRlt_k6 yPBgZ7zzoJS7kUIhQ&bvm=bv.1355325884,d.aWM. 30 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org Nichols, Austin. 2012. Receipt of Assistance by Education. Unemployment and Recovery Project Fact Sheet 5 (Washington: Urban Institute, May); available at http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct =j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CFIQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.urban.org%2Furl. cfm%3FID%3D412576&ei=h1MZUKiuMoKi8gS1hoDwCA&usg=AFQjCNE1Ufi0UtvtGhJuRg6U2olnuE-_VQ. Oklahoma Office of State Finance. 2011. State Board of Equalization Proposed FY-2013 Revenue Certification. Dec. 20. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education. 2010. Annual Headcount and Full-Time-Equivalent (FTE)* Enrollments by Division, 2008-2009 (May 7); available at http://www.okhighered.org/oeis/enrollment/ Headcount/2008-09Headcount_and_FTE.html. _______.2011. Oklahoma’s Promise 2011-12 Scholarship Rates. _______. 2011a. Overlap of Participants, OTAG/OKPromise/Acad. Scholars/OTEG). _______. 2011b. 2010-11 OK Promise Participants. _______. 2012. Earn Free College Tuition: It’s Oklahoma’s Promise! Available at http://www.okhighered.org/ okpromise/flier-english.pdf. _______. 2012a. Oklahoma’s Promise: 2010-11 Annual Report; available at http://www.okhighered.org/ okpromise/reports.shtml. _______. 2012b. Oklahoma’s Promise—Oklahoma Higher Learning Access Program Administration. Staff memorandum to Agenda Item #9-c, Meeting of January 26, 2012. Patel, Reshma and Lashawn Richburg-Hayes. 2012. Performance-Based Scholarships. Emerging Findings from a National Demonstration. New York: MDRC; available at http://www.mdrc.org/performance-based-scholarshipsemerging-findings-national-demonstration. Prince, Heath and Vickie Choitz. 2012. The Credential Differential: The Public Return to Increasing Postsecondary Credential Attainment (Washington: Center for Law and Social Policy); available at http://www. clasp.org/admin/site/publications/files/Full-Paper-The-Credential-Differential.pdf. University of Oklahoma. 2012. What OU Costs; accessed July 18, 2012 at http://www.ou.edu/content/go2/home/cost/ costs.html. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. 2012. Statistical Abstract of the United States. Table 233. Educational Attainment by State; available at http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/education/educational_ attainment.html. U.S. Department of Education. 2012. 2010-11 Federal Pell Grant End-of-Year Report. Table 22: Distribution of Federal Pell Grant Recipients by State of Legal Residence and Control of Institution; available at http:// www2.ed.gov/finaid/prof/resources/data/pell-2010-11/pell-eoy-2010-11.html. _______. 2012a. United States Education Dashboard; accessed Nov. 30, 2012 at http://dashboard.ed.gov/ dashboard.aspx. Better Benefits for Oklahoma Families (Issue 3) Oklahoma’s Promise Scholarship Program 31 32 Community Action Project www.captulsa.org