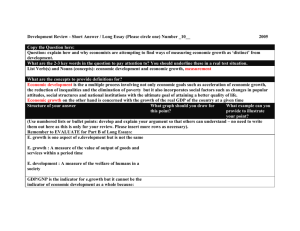

Can we see the bottom? - Repositório Institucional da Universidade

advertisement