cover - DiVA

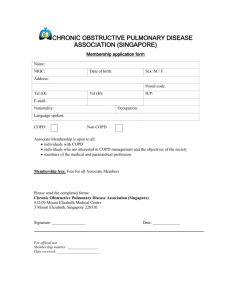

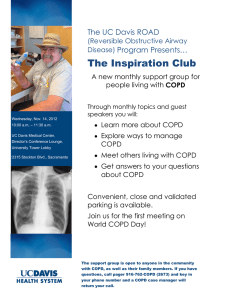

advertisement