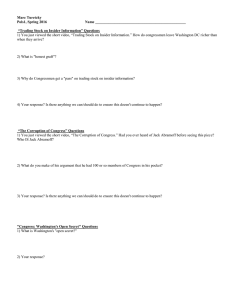

Copyright, Spleens, Blackmail, and Insider Trading

advertisement