Issue

volume fourteen • number seven

September 2008

Peer-Reviewed Journal of the

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy

Page

626

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between

Electronic Medical Records and Actual Outpatient

Medication Use

632 Prevalence and Humanistic Impact of

Potential Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder in a Commercially Insured Population

643 2008: A Tipping Point for Disease Management?

650 New Agents in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes:

Do They Provide an Opportunity for a Shift in the

Treatment Paradigm?

655

The Benefits and Risks of New Therapies for

Type 2 Diabetes

658

Diabetes Drug Therapy—First Do No Harm

661

Rethinking the “Whodunnit” Approach to Assessing the

Quality of Health Care Research—A Call to Focus on the Evidence in Evidence-Based Practice

675

Abstracts From Professional Poster Presentations at AMCP’s 2008 Educational Conference

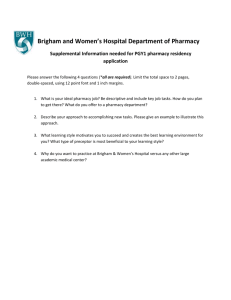

697 Managed Care Pharmacy Residencies, Fellowships, and Other Programs

volume 14, no. 7

C o n t e n t s

■ reseArCH

626 Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use

Kathleen B. Orrico, PharmD, BCPS

632 Prevalence and Humanistic Impact of Potential Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder in a Commercially Insured Population

Siddhesh A. Kamat, MS; Krithika Rajagopalan, PhD; Ned Pethick, PharmD, MBA,

Vincent Willey, PharmD; Michael Bullano, PharmD; and Mariam Hassan, PhD

■ dePArtMents

584 Cover Impressions

The Scout Sculpture Overlooking Kansas City (2005)

Richard Cummins

Sheila Macho, Cover Editor

643 Commentary

2008: A Tipping Point for Disease Management?

Brenda R. Motheral, BPharm, MBA, PhD

650 Commentary

New Agents in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes:

Do They Provide an Opportunity for a Shift in the Treatment Paradigm?

Connie A. Valdez, PharmD, MSEd

655 Commentary

The Benefits and Risks of New Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes

Carl V. Asche, PhD, and Richard E. Nelson, PhD

658 Editorial

Diabetes Drug Therapy—First Do No Harm

Frederic R. Curtiss, PhD, RPh, CEBS, and Kathleen A. Fairman, MA

661 Editorial

Rethinking the “Whodunnit” Approach to Assessing the Quality of Health Care

Research—A Call to Focus on the Evidence in Evidence-Based Practice

Kathleen A. Fairman, MA, and Frederic R. Curtiss, PhD, RPh, CEBS

675 Abstracts From Professional Poster Presentations at AMCP’s 2008 Educational Conference

697 Managed Care Pharmacy Residencies, Fellowships, and Other Programs

576 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

AMCP HeAdquArters

100 North Pitt St., Suite 400

Alexandria, VA 22314

Tel: 703.683.8416 • Fax: 703.683.8417

BoArd of direCtors

President: Cathryn A. Carroll, PhD, MBA, BSPharm,

Comprehensive Pharmacy Services, Smithville,

MO

President-Elect: Shawn Burke, RPh, FAMCP,

Coventry Health Care, Inc., Kansas City, MO

Past President: Richard A. Zabinski, PharmD,

OptumHealth; a division of UnitedHealth Group,

Golden Valley, MN

Treasurer: C.E. (Gene) Reeder, RPh, PhD, FAMCP,

Xcenda-AmerisourceBergen Specialty Group,

Columbia, SC ( JMCP liaison)

Secretary: Judith A. Cahill, CEBS,

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy,

Alexandria, VA (Executive Director, AMCP)

Director: Jean Brown, RPh, PharmD ,

Coventry Health Care, Flagstaff, AZ

Director: William K. Fleming, PharmD, RPh,

Humana, Inc., Prospect, KY

Director: Robert S. Gregory, RPh, MS, MBA,

Aetna, Inc., Hartford, CT

Director: Robert McMahan, PharmD, MBA,

Fidelis Care, Rego Park, NY

Director: Pete Penna, PharmD,

Formulary Resources, LLC, Mercer Island, WA

Advertising

Advertising for Journal of Managed Care

Pharmacy is accepted in accordance with the advertising policy of the Academy of Managed

Care Pharmacy.

For advertising information, contact:

Peter Palmer

Professional Media Group, Inc., 52 Berlin Rd.,

Suite 4000, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034

Tel.: 856.

795.5777,

Fax: 856.795.6777

ext. 13

E-mail: peter@promedgroup.net

editoriAl

Questions related to editorial content should be directed to JMCP Editor-in-Chief Frederic R. Curtiss: fcurtiss@amcp.org.

Manuscripts should be submitted electronically at jmcp.msubmit.net. For questions about submission, contact Peer Review Administrator

Jennifer A. Booker: jmcpreview@amcp.org;

703.317.0725.

suBsCriPtions

Annual subscription rates: USA, individuals, institutions–$90; other countries–$110. Single copies cost $15. Missing issues are replaced free of charge up to 6 months after date of issue.

Send requests to AMCP headquarters.

rePrints

For article reprints and Eprints, contact Theresa

Caprinolo at Sheridan Reprints, 800.352.2210, ext. 8219; tcaprinolo@tsp.sheridan.com. Microfilm and microfiche editions of Journal of Managed Care

Pharmacy are available from University Microfilms,

300 N. Zeeb Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48106. Reprint

Guidelines are available at www.amcp.org.

All articles published represent the opinions of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or views of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy or the authors’ institutions unless so specified. Copyright © 2008,

Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy.

Editorial Mission

JMCP publishes peer-reviewed original research manuscripts, subject reviews, and other content intended to advance the use of the scientific method, including the interpretation of research findings in managed care pharmacy. JMCP is dedicated to improving the quality of care delivered to patients served by managed care pharmacy by providing its readers with the results of scientific investigation and evaluation of clinical, health, service, and economic outcomes of pharmacy services and pharmaceutical interventions, including formulary management. JMCP strives to engage and serve professionals in pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and related fields to optimize the value of pharmaceutical products and pharmacy services delivered to patients. JMCP employs extensive bias-management procedures intended to ensure the integrity and reliability of published work.

Editorial staff

Editor-in-Chief

Frederic R. Curtiss, PhD, RPh, CEBS

830.935.4319, fcurtiss@amcp.org

associate Editor, Kathleen A. Fairman, MA, 602.867.1343, kathleenfairman@qwest.net

Cover Editor, Sheila Macho , 952.431.5993, jmcpcoverart@amcp.org

Peer review administrator, jmcpreview@amcp.org

Jennifer A. Booker, 703.317.0725,

Graphic designers, Leslie Goodwin, Margie Hunter

Publisher

Judith A. Cahill, CEBS, Executive Director, Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy

Editorial advisory board

The JMCP Editorial Advisory Board is chaired by Marvin D. Shepherd, PhD , Center for Pharmacoeconomic Studies,

College of Pharmacy, University of Texas at Austin; Thomas Delate, PhD, Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, Aurora, serves as vice chair.

They and the other advisers review manuscripts and assist in the determination of the value and accuracy of information provided to readers of JMCP.

Carl Victor Asche, PhD, MBA,

Salt Lake City

John P. Barbuto, MD,

Jingdong Chao, PhD,

Edina, MN

East Hanover, NJ

College of Pharmacy, University of Utah,

HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital, Sandy, UT

Chris F. Bell, MS, Global Health Outcomes, GlaxoSmithKline Research

& Development, Research Triangle Park, NC

Joshua Benner, PharmD, ScD, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

Eliot Brinton, MD, School of Medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City

Leslee J. Budge, MBA, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA

Scott A. Bull, PharmD, ALZA Corporation, Mt. View, CA

Norman V. Carroll, PhD, School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth

University, Richmond, VA

Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL

Eric J. Culley, PharmD, MBA, Highmark Blue Shield, Pittsburgh, PA

Gregory W. Daniel, RPh, MPH, PhD, HealthCore, Inc., Wilmington, DE

Quan V. Doan, PharmD, MSHS, Outcomes Insights, Inc., Orange, CA

Lida R. Etemad, PharmD, MS, UnitedHealth Pharmaceutical Solutions,

Patrick R. Finley, PharmD, BCPP, University of California at San Francisco

Feride Frech-Tamas, MPH, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.,

Patrick P. Gleason, PharmD, BCPS, Prime Therapeutics, LLC, Eagan, MN

Charnelda Gray, PharmD, BCPS, Kaiser Permanente, Atlanta, GA

Ann S. M. Harada, PhD, MPH, Prescription Solutions, Irvine, CA

Noelle Hasson, PharmD, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System,

Palo Alto, CA

Lillian Hsieh, MHS, PharmD candidate, School of Pharmacy, University of California, San Francisco

Mark Jackson, BScPharm, BComm, RPh, Green Shield Canada,

Windsor, Ontario

Richard A. Kipp, MAAA, Milliman USA, Wayne, PA

Stephen J. Kogut, PhD, MBA, College of Pharmacy, University of

Rhode Island, Kingston

Joanne LaFleur, PharmD, MSPH, College of Pharmacy, University of Utah,

Salt Lake City

Daniel C. Malone, PhD, RPh, College of Pharmacy, University of Arizona,

Tucson

Bradley C. Martin, PharmD, PhD, College of Pharmacy, University of

Arkansas, Little Rock

Lynda Nguyen, PharmD candidate, School of Pharmacy, University of

California, San Francisco

Robert L. Ohsfeldt, PhD, School of Rural Public Health, Texas A&M

Health Science Center, College Station

Steven Pepin, PharmD, BCPS, PharmWorks, LLC, Arden Hills, MN

Mary Jo V. Pugh, PhD, South Texas Veterans Healthcare System,

San Antonio, TX

Brian J. Quilliam, PhD, RPh, College of Pharmacy, University of Rhode

Island, Kingston

Gene Reeder, RPh, PhD, Xcenda, Columbia, SC (AMCP Board Liaison)

Elan Rubinstein, PharmD, MPH, EB Rubinstein Associates, Oak Park, CA

Fadia T. Shaya, PhD, MPH, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland,

Baltimore

Denise Sokos, PharmD, BCPS, School of Pharmacy, University of

Pittsburgh, PA

Brent Solseng, PharmD, BlueCross BlueShield of North Dakota, Fargo

Joshua Spooner, PharmD, MS, Advanced Concepts Institute, Philadelphia, PA

Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, CHW Medical Foundation, Rancho Cordova,

CA; University of California, San Francisco

Kent H. Summers, RPh, PhD, School of Pharmacy, Purdue University,

West Lafayette, IN

Connie A. Valdez, PharmD, MSEd, Health Sciences Center, University of

Colorado, Denver

Robert J. Valuck, RPh, PhD, School of Pharmacy, University of Colorado

Health Sciences Center, Denver

Peter Whittaker, PhD, School of Medicine, Wayne State University,

Detroit, MI

Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy (ISSN 1083–4087) is published 9 times per year and is the official publication of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP),

100 North Pitt St., Suite 400, Alexandria, VA 22314; 703.683.8416; 800.TAP.AMCP; 703.683.8417 (fax). The paper used by the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper) effective with Volume 7, Issue 5, 2001; prior to that issue, all paper was acid-free. Annual membership dues for AMCP include $60 allocated for the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to JMCP , 100 North Pitt St., Suite 400, Alexandria, VA 22314.

582 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

c o v e r i m p r e s s i o n s

A b o u t o u r c o v e r a r t i s t

The Scout Sculpture Overlooking Kansas City

(2005) n

Richard Cummins

L ighthouses ultimately led the way to 2 different careers for Richard

Cummins. Growing up in the city of Cork, Ireland, he worked on a fishing boat during the summers while he was in high school, and often passed by some of

Ireland’s majestic lighthouses. Cummins was fascinated by the towering structures and decided that he wanted to become a lighthouse keeper someday. To achieve his goal, he studied at the Commissioners of

Irish Lights maritime school in Dublin.

After graduation, Cummins served 10 years in the Irish Lighthouse Service, working at most of the nation’s lighthouses.

“I love shooting cities—trying to extract details to show the individuality of a city.”

“I first got into photography to show my family and friends the

Irish lighthouses and the spectacular scenery surrounding them,” he explains. “I eventually had several images published in books in Ireland. When my wife and I emigrated to Southern California in 1989, I continued to pursue photography, but only as a hobby.

After a few years, I won the Sierra Club national photography contest and the National Geographic Traveler photo contest, and headquarters in San Francisco. Many of his stunning photographs can be seen on his

Web site (richardcumminsphotos.com).

In addition to his own stock photography agency (with more than 100,000 photos on file), he contributes images to quite a few of the major stock photo companies.

Cummins, who has taken photos in urban and rural areas all over the world, finds cities particularly intriguing. “I love shooting cities—trying to extract details to show the individuality of a city,” he says.

In 2005, he accepted an assignment to take pictures for various Kansas City, Missouri, tourism books. One of the most compelling images from that photo shoot is The Scout

Sculpture Overlooking Kansas City.

Cummins used a Canon ELAN film camera equipped with a Canon EF 100-300mm zoom lens to capture The Scout gazing upon downtown Kansas City.

A famous icon in Kansas City, The Scout statue stands more than 10 feet tall and depicts a Sioux Indian on horseback as he returns from hunting. Cyrus E. Dallin of Arlington, Massachusetts, sculpted The Scout in 1914 for the Panama-Pacific International this led to other images being published.” Before Cummins knew it, he was making a living as a professional photographer. In 1996,

Cummins and his wife Catherine launched the Richard Cummins

Stock Photography agency, which has proven to be very successful. They became naturalized U.S. citizens in 2000.

As a self-taught photographer, Cummins learned his craft by reading photography books and carefully studying the images of other photographers. His work is best described as graphic with bold splashes of color. “My favorite style of photography is ‘Light

Painting,’ an old turn-of-the-century photographic technique in which you light the subject during long exposures,” he says.

“I spend many hours in the California desert at night lighting the landscape with huge spotlights covered with colored filters.

Creating one shot can last from a few minutes to several hours.”

Cummins specializes in travel and landscape photography and has received many awards, including 2 from the United

Nations Photographic Council. His photos and accompanying articles have appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers, including Time, U.S. News & World Report, Popular Photography , the

Los Angeles Times , and The Observer . Cummins has also written and photographed a children’s book about Ireland and recently completed a book for the National Park Service featuring the

Cabrillo National Monument in San Diego. Other publishers that have used his images include Houghton Mifflin, Time-Life Books,

Macmillan, Frommer’s, and AAA Publications.

Cummins’ fine-art photographic prints have been exhibited in several galleries in California and Ireland, as well as New York’s

Rockefeller Center, the City of Palm Springs, and the Sierra Club

Exposition (1915 World’s Fair) held in San Francisco, where it won a gold medal. On its way back east, the sculpture was exhibited in Kansas City’s Penn Valley Park. The Scout was so popular, the citizens wanted it to stay. Dallin agreed to a price of $15,000, which was raised in nickels and dimes by local children who called themselves “The Kids of Kansas City.” The Scout statue was permanently installed in Penn Valley Park and dedicated as a memorial to indigenous Indian tribes. Several area attractions have been named after the bronze work of art, most notably

“Kansas City Scout,” Kansas City’s traffic management system.

Also of interest is a nearly identical sculpture located in Seville,

Spain—Kansas City’s sister city. The 2 statues point toward each other across the globe.

If you are attending AMCP’s 2008 Educational Conference in Kansas City October 15-18 and would like to see the scene depicted in Cummins’ beautiful photograph, Penn Valley Park is located just south of the Liberty Memorial in downtown Kansas

City.

Sheila Macho

COVER CREDIT

Richard Cummins, The Scout Sculpture Overlooking Kansas City , analog photograph. Kansas City, Missouri, 2005.

Copyright© Richard Cummins/Lonely Planet Images.

SOURCE

Interview with the artist.

Cover Editor

584 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

Jmcp

Editorial Policy

■■ Editorial Content and Peer Review

All articles, editorials, and commentary in JMCP undergo peer review; articles undergo blinded peer review. Letters may be peer reviewed to ensure accuracy. The funda mental departments for manuscript submission are:

• Research

• Subject Reviews

• Formulary Management

• Contemporary Subjects

• Brief Communications

• Commentary/Editorials

• Letters

All submissions other than Editorials,

Commentary, and Letters should include an abstract and inform the reader at the end of the manuscript of what is already known about the subject and what the article adds to our knowledge of the subject.

For manuscript preparation requirements, see “ or at

JMCP Author Guidelines”

www.amcp.org.

in this Journal editori a l M ission a nd pol icies

JMCP publishes peer-reviewed original research manuscripts, subject reviews, and other content intended to advance the use of the scientific method, including the interpretation of research findings in managed care pharmacy. JMCP is dedicated to improving the quality of care delivered to patients served by managed care pharmacy by providing its readers with the results of scientific investigation and evaluation of clinical, health, service, and economic outcomes of pharmacy services and pharmaceutical interventions, including formulary management. JMCP strives to engage and serve professionals in pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and related fields to optimize the value of pharmaceu tical products and pharmacy services delivered to patients.

JMCP employs extensive bias-management procedures that include (a) full disclosure of all sources of potential bias and conflicts of interest, nonfinancial as well as financial; (b) full disclosure of potential conflicts of interest by reviewers as well as authors; and (c) accurate attribution of each author’s contribution to the article. aggressive bias-management methods are necessary to ensure the integrity and reliability of published work.

editorial content is determined by the editor-in-chief with suggestions from the editorial advisory Board. the views and opinions expressed in JMCP do not necessarily reflect or represent official policy of the academy of Managed care pharmacy or the authors’ institutions unless specifically stated.

■■ Research

These are well-referenced articles based on original research that has not been published elsewhere and reflect use of the scientific method. The research is guided by explicit hypotheses that are stated clearly by the authors.

■■ Subject Reviews

These are well-referenced, comprehensive reviews of subjects relevant to managed care pharmacy. The Methods section in the abstract and in the body of the manuscript should make clear to the reader the source of the material used in the review, including the criteria used for inclusion and exclusion of information.

■■ Formulary Management

These are well-referenced, comprehensive reviews of subjects relevant to formulary management methods or procedures in the conduct of pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees and may include description and interpretation of clinical evidence.

■■ Contemporary Subjects

These are well-referenced submissions that are particularly timely or describe research conducted in pilot projects. Contemporary

Subjects, like all articles in JMCP , must describe the hypothesis or hypotheses that guided the research, the principal methods, and results.

■■ Brief Communications

The results of a small study or a descriptive analysis that does not fit in other JMCP departments may be submitted as a Brief

Communication.

■■ Editorials/Commentary

These submissions should be relevant to managed care pharmacy and address a topic of contemporary interest: they do not require an abstract but should include references to support statements.

■■ Letters

If the letter addresses a previously published article, an author response may be appropriate. (See “Letter to the Editor” instruc tions at www.amcp.org.)

■■ Advertising/Disclosure Policy

A copy of the full advertising policy for JMCP is available from AMCP headquarters and the

Advertising Account Manager. All aspects of the advertising sales and solicitation process are completely independent of the editorial process. Advertising is positioned either at the front or back of the Journal ; it is not accepted for placement opposite or near subjectrelated editorial copy.

Employees of advertisers may submit articles for publication in the editorial sections of JMCP , subject to the usual peerreview process. Financial disclosure, conflict-of-interest statements, and author attestations are required when manuscripts are submitted, and these disclosures generally accompany the article in abstracted form if the article is published.

See “Advertising Opportunities” at www.amcp.org. Contact the Advertising

Representative to receive a Media Kit.

Editorial Office

Academy of Managed Care

Pharmacy

100 North Pitt St., Suite 400

Alexandria, VA 22314

Tel.: 703.683.8416

Fax: 703.683.8417

Email: jmcpreview@amcp.org

Advertising Sales Office

Professional Media Group, Inc.

52 Berlin Rd., Suite 4000

Cherry Hill, NJ 08034

Tel.: 856.795.5777, ext. 13

Fax: 856.795.6777

Email: peter@promedgroup.net

618 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

JMCP

Author Guidelines

JMCP accepts for consideration manuscripts prepared

according to the Uniform Requirements for Manu scripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

1

■■ Manuscript Preparation

Manuscripts should include, in this order: title page, abstract, text, references, tables, and figures (see Submis sion Checklist for details).

JMCP abstracts should be carefully written narratives that contain all of the principal quantitative and qualita tive findings, with the outcomes of statistical tests of comparisons where appropriate. Abstracts are required for all articles in Research, Subject Reviews, Formulary

Management, Contemporary Subjects, and Brief Commu nications. The format for the abstract is Background,

Objective, Methods, Results, Conclusion. Editorials and Commentary do not require an abstract but should include references. Letters do not require an abstract.

For descriptions of editorial content, see “ JMCP

Editorial Policy” in this Journal or at ww.amcp.org.

Please note:

• The JMCP Peer Review Checklist is the best guide for authors to improve the likelihood of success in the

JMCP peerreview process. It is available at: www.

amcp.org (Peer Reviewers tab).

• A subsection in the Discussion labeled “Limitations” is generally appropriate for all articles except Editorials,

Commentaries, and Letters.

• Most articles, particularly Subject Reviews, should incorporate or at least acknowledge the relevant work of others published previously in JMCP (see “Article

Index by Subject Category” at www.amcp.org).

• For most articles in JMCP , a flowchart is recom mended for making the effects of the inclusion and exclusion criteria clear to readers (see JMCP examples in 2007; 13(3):237 (Figure 1), or 2007; 13(1):22 (Figure

1), or 2006; 12(3):234 (Table 3).

• Product trade names may be used only once for the purpose of providing clarity for readers, generally at the first citation of the generic name in the article but not in the abstract.

• Many articles involve research that may pose a threat to either patient safety or privacy. It is the responsibil ity of the principal author to ensure that the manu script is submitted with either the result of review by the appropriate institutional review board (IRB) or a statement of why the research is exempt from IRB review (see JMCP Policy for Protecting Patient Safety and Privacy at www.amcp.org).

■■ Reference Style

References should be prepared following modified

AMA style. All reference numbers in the manuscript should be superscript (e.g., 1 ). Each unique reference should have only one reference number. If that refer ence is cited more than once in the manuscript, the same number should be used. Do not use ibid or op cit for JMCP references. Please provide Web addresses for references whenever possible. See the following exam ples of common types of references:

1.

Journal articles (list up to 6 authors; if more, list only the first 3 and add et al.)—Kastelein JJP, Akdim F,

Stroes ESG, et al., for the ENHANCE Investigators.

Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hyper cholesterolemia. N Engl J Med . 2008;358(14):143143.

2.

No author given — Anonymous. Top 25 U.S. hospitals, ranked by admissions, 1992. Manag Healthcare . 1994;

4(9):64.

3.

Journal paginated by issue— Gregory DW,

Malone DC. Characteristics of older adults who meet

The Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, including supplements, is indexed by MEDLINE/PubMed, the International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA),

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Current

Contents/Clinical Medicine (CC/CM), and Scopus.

the annual prescription drug expenditure threshold for

Medicare medication therapy management programs.

J Manag Care Pharm . 2007;13(2):14254. Available at: www.amcp.org/data/jmcp/p14254.pdf.

4.

Book or monograph by authors— Tootelian DH,

Gaedeke RM. Essentials of Pharmacy Management .

St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1993.

5.

Book or monograph with editor, compiler, or chairperson as author— Chernow B, ed. Critical Care Pharma cotherapy . Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.

6.

Chapter in a book— Kreter B, Michael KA, DiPiro JT.

Antimicrobial pro phyl axis in surgery. In: DiPiro JT,

Talbert RL, Hayes PE, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach .

Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1992:1811-12.

7.

Government agency publication— Akutsu T. Total heart replacement device. Bethesda, MD: National

Institutes of Health, National Heart, Blood, and Lung

Institute; April 1974. Report no.: NIHNHLI692185 4.

8.

Dissertation or thesis— Youssef NM. School adjust ment of children with congenital heart disease [disserta tion]. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; 1988.

9.

Drug Label —BristolMyers Squibb Company. Gluco phage (metformin hydrochloride tablets); Glucophage XR

(metformin hydrochloride extendedrelease tablets)

[prescribing information]. June 2006.

10.

Letter or editorial

Markson, LE, Bukstein, DA, Luskin AT. Health care uti lization determined from administrative claims analysis for patients who received inhaled corticosteroids with either montelukast or salmeterol [letter]. J Manag Care

Pharm . 2006;12(6):48687. Available at: www.amcp.org/ data/jmcp/letter_486487.pdf.

11.

Paper (or Poster) presented at a meeting Reagan

ME. Workers’ compensation, managed care, and reform.

Poster presented at: 1995 AMCRA Midyear Managed

Care Summit; March 13, 1995; San Diego, CA.

12.

Newspaper article— Lee G. Hospitalizations tied to ozone pollution: study estimates 50,000 admissions annually. Wash Post . June 21, 1996;A:3.

13.

Web site— National Heart, Lung, and Blood Insti tute. Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Full report 2007 (EPR3: full report 2007). Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guide lines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2007.

14.

Supplement— AMCP Task Force on Drug Payment

Methodologies: AMCP guide to pharmaceutical payment methods [suppl]. J Manag Care Pharm . 2007;13(8, Sc):

S1S40. Available at: www.amcp.org/data/jmcp/

JMCPSUPPC_OCT07.pdf.

■■ Manuscript Submission

Please submit manuscripts electronically at jmcp. msubmit.net.

All text should be submitted in Microsoft

Word, prepared in 12point type, 1.5 line spacing. Tables must be prepared in either Microsoft Word or Excel and may use a smaller text (e.g., 10point). Figures should be submitted in their original native format, preferably

Adobe Illustrator or Photoshop. Figures may also be pre pared in Microsoft Word, but please send original native files rather than embedded images (tables or figures) to permit editing by the JMCP graphic designer. The JMCP graphic designer has permission to recreate any figures.

Please identify each file submitted with the following information: format (PC or MAC), software application, and file name.

Note: Please do not include author identification in the electronic manuscript document.

Technical style: P values should be expressed to no more than 3 decimal points in the format 0.xxx, to 3 decimal places.

Cover letter: the corresponding (lead) author should include a cover letter with the manuscript, which

• briefly describes the importance and scope of the manuscript, and

• certifies that the paper has not been accepted for publication or published previously and that it is not under consideration by any other publication.

Disclosures and conflicts of interest: Manuscript submissions should include a statement that identifies the nature and extent of any financial interest or affilia tion that any author has with any company, product, or service discussed in the manuscript and clearly indi cates the source(s) of funding and financial support and be accompanied by completed and signed author attesta tion forms for the principal author and each coauthor.

All manuscripts are reviewed prior to peer review.

Manuscripts may be returned to authors prior to peer review for clarification or other revisions. Peer review generally requires 4 weeks but may extend as long as

12 weeks in unusual cases. Solicited manuscripts are subject to the same peerreview standards and editorial policy as unsolicited manuscripts.

■■ Submission Checklist

Before submitting the paper copy of your manuscript to the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy , please check to see that your package includes the following:

❑ Cover letter

❑ Manuscript: prepared in 12point type, 1.5 line spacing, including

• abstract: no more than 650 words

• references: cited in numerical order as they appear

in the text (use superscript numbers) and prepared

following modified AMA style; do not include

footnotes in the manuscript

• tables and figures (generally no more than a total

of 6). Submit referenced tables and figures on separate

pages with titles (and captions, as necessary) at the

end of the manuscript; match symbols in tables and

figures to explanatory notes, if included. May use

10point type.

• information indicating what is known about the

subject and what your article adds.

❑ Disclosures and conflict-of-interest forms: completed and signed author attestation forms (available at www.

amcp.org); clearly indicate source(s) of funding and financial support.

Note: Please do not include author identification in the electronic manuscript document.

For “Manuscript Submission Checklist” and “Peer Review

Checklist,” see www.amcp.org.

RefeReNCe

1. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. Updated July 27, 2008. Available at: www.

icmje.org/. Accessed April 14, 2007.

622 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

R E S E A R C H

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic Medical

Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use

Kathleen B. Orrico, PharmD, BCPS

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Accuracy and transportability of the recorded outpatient medication list are important in the continuum of patient care. Classifying discrepancies between the electronic medical record (EMR) and actual drug use by the root cause of discrepancy (either system generated or patient generated) would guide quality improvement initiatives.

OBJECTIVES: To quantify and categorize the number and type of medication discrepancies that exist between the medication lists recorded in EMRs and the comprehensive medication histories obtained through telephone interviews conducted by a team of nurses providing advice to health plan members at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation in Palo Alto, California.

METHODS: The study was conducted as a retrospective comparison of EMR medication lists with information obtained by patient interview. Interview data were obtained by a review of telephone calls made to a nurse advice line by health plan members seeking information about sinusitis, urinary tract infection, acute conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, emergency contraception, or mastitis. As part of the advice protocol, a medication reconciliation process was conducted between July 1 and December 31, 2006. Changes to the medication list made during the telephone visit were extracted, categorized, and evaluated by the study’s principal investigator. Data extraction included the number and type of identified medication discrepancies, patient age, gender, and condition that prompted the telephone contact.

A modified version of the Medication Discrepancy Tool (MDT) was used to categorize medication discrepancies as either system generated (e.g., failure of the provider to update a medication list) or patient generated (e.g., failure of the patient to report use of an over-the-counter product).

RESULTS: A total of 233 discrepancies were identified from 85 medication reconciliation phone visits, averaging 2.7 per medication list. The most common type of discrepancy was a medication recorded in the EMR but no longer being used by the patient (n=164, 70.4%), followed by omission from the EMR of a medication being taken by the patient (n=36, 15.5%).

79.8% (n=186) of the discrepancies were attributed to system-generated factors, whereas 20.2% (n=47) were patient generated. Approximately half (n=118, 50.6%) of the discrepancies fell into 4 broad American

Hospital Formulary System therapeutic classifications: anti-infective agents (14.2%), anti-inflammatory agents (14.2%), analgesics (12.4%), and vitamins (9.9%). The most common patient-generated discrepancy was omission of a multivitamin (n=13, 27.7%), and the most common systemgenerated prescription drug discrepancy was expired entry for the intranasal corticosteroid mometasone furoate (n=12, 6.5%).

CONCLUSION: Discrepancies in the outpatient setting were common and predominantly system generated. The most common discrepancy was the presence in the EMR of a medication no longer being taken by the patient.

Adding foreseeable end dates to prescription drug orders at computerized order entry might be considered in an effort to improve the accuracy of the outpatient medication list. Reliable systems to involve patients in routinely reconciling EMRs with actual medication use may also warrant examination. The MDT methodology served as a useful qualitative guide for evaluating discrepancies and developing targeted means for resolution.

J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(7):626-631

Copyright © 2008, Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. All rights reserved

What is already known about this subject

• At hospital admission, an estimated 60%–67% of medication histories contain at least 1 error, either omission of a medication being taken, or reporting of a medication not being used. An estimated 11%–59% of these errors are clinically important.

• A comparison of hospital discharge orders and a comprehensive medication assessment conducted after discharge identified medication discrepancies in 14.1% of patients aged 65 years and older and with at least 1 chronic condition. Of these discrep ancies, 50.8% were patient generated and 49.2% were system generated.

What this study adds

• For 85 outpatients contacting a health plan medical advice line for assistance with relatively minor medical conditions, a total of 407 medication entries in an electronic medical record (EMR) were identified. Of those, 233 (57.2%) did not match to infor mation obtained using a comprehensive medication assessment conducted telephonically by a nurse.

• In the majority (70.4%) of discrepancies between EMR entries and medication assessments, a medication recorded in the EMR was no longer being taken by the patient.

• 79.8% of the discrepancies were system generated, whereas

20.2% were patient generated.

626 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic

Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use

M any studies evaluating medication reconciliation have focused on activities occurring at times of transi tion during or immediately following hospital care.

1–6

Cornish et al. reported that upon hospital admission, few patients could produce an accurate account of their current medication regimens, and that the most common error identified in the medication use history was the omission of a regularly used medication (46.4%).

1 Because the genesis of most prescription drug orders occurs in the physician office setting, improving the accuracy and transportability of the recorded outpatient medica tion list would extend a measure of quality throughout the con tinuum of patient care.

People are particularly vulnerable for experiencing medica tion mishaps during care transitions such as hospital discharge.

Coleman et al.’s study of 375 elderly patients assessed 1 week post-hospitalization showed that 14.1% had experienced 1 or more medication discrepancies, defined as a lack of agreement between prescribed drug therapy indicated on the hospital dis charge record and the therapy actually received by the patient.

2

The study used the Medication Discrepancy Tool (MDT), a meth odology developed and tested for reliability by Smith et.al, to cat egorize these transition-related discrepancies as being generated at either the system level (i.e., under the control of providers) or the patient level (i.e., under the control of patients).

3 Of the 124 discrepancies identified in the Coleman et al. study, 49.2% were categorized as system generated and 50.8% were categorized as patient generated.

2 A systematic review of studies of medication errors at hospital admission indicated that 60%–67% of prescrip tion medication histories contained at least 1 error, either the omission of a medication being taken by the patient or the report ing of a medication not being taken. An estimated 11%–59% of these errors were deemed clinically important.

6

The objective of this study was to determine the state of accu racy of the outpatient medication list by quantifying and catego rizing medication discrepancies between the recorded medica tion list contained in the EMR and a comprehensive medication history obtained through telephone interview by an advice nurse at the Palo Alto Medical Clinic (PAMC). The intended use of a modified MDT to classify the root cause of each discrepancy as either system or patient generated was to allow quality improve ment activities to be appropriately devised and directed.

■■ Methods

Study Setting and Patient Population

The study was conducted at the PAMC, a division of the Palo Alto

Medical Foundation for Health Care, Research, and Education located in Northern California, and was approved by the Palo

Alto Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board. The foun dation is an affiliate of Sutter Health, a system of not-for-profit hospitals and physician organizations. PAMC, a multispecialty medical group with approximately 250 physicians and 900 other professionals at its main facility and 4 satellite clinics, is respon sible for approximately 190,000 covered enrollees.

In 2002, PAMC implemented a full-featured EMR, allow ing electronic documentation of all clinician activity, including computerized medication order entry and the generation of a medication list. Because prescription order entry is a universally used feature, the medication list contains all prescription orders generated at PAMC, including scheduled medications (i.e., con trolled substances). Prescription orders are entered into the sys tem and sent by fax to any retail pharmacy. The physician also can generate printed copies of prescriptions, including scheduled medications, which are routed to secure printers containing tam per-proof forms as required by California law. The system allows for entry of over-the-counter (OTC) items, herbal medications, and nutraceuticals. As a standard practice at PAMC, medications prescribed by providers outside of PAMC but reported as being actively received by the patient are recorded on the medication list and given the system designation of “historical medication,” indicating that the information is patient reported.

The study was conducted as a retrospective, encounter-based

EMR review of telephone calls made to a nurse advice line in the PAMC Department of Family Medicine from July through

December 2006. Registered nurses are authorized to enact stan dardized procedures and telephone treatment protocols for the following complaints: acute conjunctivitis, emergency contracep tion, mastitis in breast feeding women, pharyngitis, sinusitis, and urinary tract infection in women. To qualify to enact these protocols, a nurse must have at least 2 years of prior experience as a registered nurse, have a current California nursing license, and have passed an initial and annual competency evaluation. Only patients who received their primary care at PAMC and who met specific symptom criteria for 1 of the 6 conditions listed above were eligible for telephone treatment and received medication reconciliation. A sample was identified for review by randomly selecting 10 clinic log sheets from approximately 150 clinic log sheets recorded during the 6-month data collection time period.

Each log sheet listed the date of service and medical record num ber of the patient receiving medication reconciliation. No other restrictions were placed on the group of patients included in the study.

Beginning in July 2006, the 8 advice-line nurses began to incorporate a medication reconciliation process into their usual workflow. During the telephone visit (encounter), patients were asked to verify their current medication regimen and to include medications prescribed by physicians outside of PAMC, OTC medications, and herbal preparations. The nurse first verified the medication list by naming each recorded medication using both the generic and brand name, if applicable, and then asking the patients whether they were actively taking that medication. The dose, frequency, and route of administration were also verified with the patient. For medications prescribed on an as-needed basis, such as medications for pain or allergies, patients were asked whether they had used the drug within the past year. The www.amcp.org Vol. 14, No. 7 September 2008 JMCP Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 627

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic

Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use medication was left on the medication list if the patient reported use within the past year or if the patient requested that it remain listed. Next, the patient was asked to report any active use of OTC items, herbal supplements, nutraceuticals, vitamins, and any other prescription medication not recorded on the medication list, including medications prescribed by providers not affiliated with PAMC. At the end of the interview, the nurse updated the medication list. Electronic notification was sent to the primary care physician for review and approval of all changes made including additions and deletions.

Medication Discrepancy Classification

Changes and updates to the medication list enacted during the

85 telephone visits were extracted, quantified, and classified using a retrospective comparison with the EMR. Data extraction was conducted by the principal investigator, and each alteration made to the medication list during the nurse visit was trans ferred to Microsoft Excel worksheets for categorization. The medical record number was the only patient identifier extracted.

Additional data points extracted included patient age, sex, date of visit, and which of the 6 medical conditions prompted the call to the advice line.

For the purpose of this evaluation a “discrepancy” was defined as any lack of agreement between the medication list in the EMR and the patient-reported medication regimen. Discrepancies included any incongruity in medication, dose, frequency, or route, as well as any omission, duplication of the same medi cation in the EMR list, or drug no longer being taken by the patient remaining current on the EMR list. Each discrepancy was assigned to a therapeutic classification based on the American

Hospital Formulary Service (AHFS) standard.

7 The AHFS thera peutic classification categories are extremely broad and can include oral, ophthalmic, topical, nasal, inhaled, and oral agents.

For example, the classification of anti-inflammatory drugs would include oral methylprednisolone tablets, montelukast tablets, mometasone nasal spray, fluticasone inhalation, desonide topical, and hydrocortisone suppositories.

Discrepancies also were assigned to categories based on the

MDT methodology developed by Smith et al.

3 The MDT was created to identify health care facility transition-related medica tion discrepancies and assign them to actionable categories. A main element of the MDT is the classification of each discrep ancy as being either system generated or patient generated. This initial assignment allows for the analysis of the root cause of a discrepancy. A system-generated discrepancy occurred if the physician or a health system process was deemed to have control or responsibility for the medication list inaccuracy. An example of a system-generated discrepancy in the outpatient record was the current listing on the medication list of an antibiotic, such as ciprofloxacin for the treatment of a urinary tract infection, long after the course of therapy had been completed. A discrepancy was classified as patient generated if it occurred because of a fac tor under the patient’s control. An example of a patient-generated discrepancy was the omission from the medication list of a daily multivitamin that the patient initiated; this discrepancy is consid ered patient generated, because the only means for inclusion of this product in the EMR is through patient report.

In accordance with the MDT methodology, discrepancies were further classified into subcategories based on contributing fac tors. The intent of this action is to explore the frequency, causes, and contributing factors to the generation of medication discrep ancies. Adaptations of the original tool were made to make the subcategorization more applicable to the study. For example,

MDT subcategories such as “Did not fill prescription” and “No caregiver” did not apply to this study setting. For the purpose of this study, subcategories included duplicate entry of the same generic entity, omission from the EMR of a medication that the patient reported receiving, erroneous entry of either the dose or directions, and inclusion on the EMR of a medication that the patient reported no longer receiving.

To identify causal factors and provide guidance for corrective action planning, a third categorization scheme that was not part of the original MDT was added to the analysis. Each systemgenerated discrepancy was categorized as caused by (a) an end date not entered at the time of prescribing when it was foresee able to determine length of therapy or (b) failure to update the medication list. Patient-generated discrepancies were categorized as caused by (a) OTC medication/product being taken by the patient but not listed in the EMR, (b) prescription medication prescribed by a non-PAMC provider, or (c) reported intentional nonadherence. Discrepancies involving OTC medications and those prescribed by non-PAMC physicians (historical medica tions) are classified as patient generated because the patient has firsthand knowledge of current use; thus, strategies to resolve the discrepancy depend on updates provided by the patient.

■■ Results

Population Characteristics

The 85 evaluated medication reconciliation telephone calls were associated with 85 unique patients who were all assigned to a primary care provider at PAMC. Because the study included only patients who met specific symptom criteria for 1 of the 6 condi tions managed by telephone treatment protocol, the study popu lation was skewed towards women (female n=69 [81.2%]), with a mean (SD) age of 42 (14) years (Table 1). Medical conditions reported by callers included: sinusitis (n=38, 44.7%), urinary tract infection in adult women (n=26, 30.6%), acute conjunctivitis

(n=9, 10.6%), pharyngitis (n=7, 8.2%), emergency contraception

(n=4, 4.7%), and mastitis in breastfeeding women (n=1, 1.2%).

Types of Medication Discrepancies

The 85 recorded medication lists contained a total of 407 current medication entries, an average of 4.8 entries per list. A total of

233 discrepancies were identified (average of 2.7 per list) and cat -

628 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic

Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use egorized as resulting from duplicate entries (n=27, 11.6%), active medications omitted from the profile (n=36, 15.5%), medications recorded in the EMR but no longer being taken (n=164, 70.4%), and differences in dosage or directions (n=6, 2.6%; Table 2).

Each discrepancy was further classified as being either system-generated (n=186, 79.8%) or patient-generated (n=47,

20.2%; Table 2). The majority (n=155, 83.3%) of the 186 systemgenerated discrepancies resulted from discontinued or expired medications that had been left active on the medication list. The most frequently occurring patient-generated discrepancies (n=36,

76.6%) resulted from omission from the EMR of OTC medica tions and those prescribed by providers outside of PAMC.

Categorization of discrepancies based on causal factors is sum marized in Table 3. An actionable causation factor for approxi mately half (48.4%) of the system-generated discrepancies was the lack of the entry of an end date for medications with known lengths of therapy. A causal factor for more than half (61.7%) of the patient-generated discrepancies was the lack of documenta tion for active OTC medication or product use.

-

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Outpatients Telephoning a Health Plan Nurse Advice Line

Number of unique patients

Age (years) mean (SD)

Variable

Age range (years), by age category

18–89

18–39

40–59

60–89

Male

Female

Medical Condition Reported by Patient

Sinusitis

Urinary tract infection in women

Acute conjunctivitis

Pharyngitis

Emergency contraception

Mastitis in breastfeeding women

85

42 (14)

N (%)

34 (40.0)

45 (52.9)

6 (7.1)

16 (18.8)

69 (81.2)

38 (44.7)

26 (30.6)

9 (10.6)

7 (8.2)

4 (4.7)

1 (1.2) Medication Classes

Half of the 233 identified discrepancies (n=118, 50.6%) fell into

4 broad AHFS medication classes: anti-infective agents (14.2%), anti-inflammatory agents (14.2%), analgesics (12.4%), and vita mins (9.9%; Table 4). The first 3 categories contained medications that typically have a finite or seasonal course of use (antibiotics, analgesics, nasal corticosteroids). The omission of a multivitamin from the EMR list was the most commonly occurring patientgenerated discrepancy (n=13, 27.7%, data not shown). An entry for the intranasal corticosteroid mometasone furoate, a seasonal anti-inflammatory agent, was the prescription drug most com monly occurring as a system-generated discrepancy because it remained on the medication list after active use had stopped

(n=12, 6.5%, data not shown).

■■ Discussion

The results of the study showed that the EMR medication list contained many discrepancies, the majority of which were attrib utable to system-generated factors. True inaccuracies, such as the entry into the EMR of an incorrect dose or frequency or the entry of a duplicate order entry, were rare. Because the majority of discrepancies were the result of discontinued medications being allowed to remain on the list long after the course of therapy had been completed, it follows that discrepancies fell into therapeutic classifications that have a finite or seasonal, rather than chronic, treatment course.

TABLE 2 Categorization of Medication Discrepancies by System-Generated and Patient-Generated Factors

Factors Definition

Duplicate entry Generic entity listed more than once

Omission from EMR Patient reports currently receiving a medi cation that is not listed

Patient not receiving—current on EMR Medication present on EMR, but patient reports not currently receiving

Erroneous entry—dose Medication entry on EMR shows different dose than what patient reports receiving

Erroneous entry—directions Medication entry on EMR shows differ ent directions than what patient reports receiving

EMR=electronic medical record

System Generated n (%)

186 (79.8)

27 (14.5)

0

155 (83.3)

3 (1.6)

1 (0.5)

Patient Generated n (%)

47 (20.2)

0

36 (76.6)

9 (19.1)

1 (2.1)

1 (2.1)

Total n (%)

233 (100)

27 (11.6)

36 (15.5)

164 (70.4)

4 (1.7)

2 (0.9) www.amcp.org Vol. 14, No. 7 September 2008 JMCP Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 629

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic

Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use

TABLE 3 Medication Discrepancies:

Causal Factors

System-Generated Factors n=186

Medication list not updated

End date not entered

Patient-Generated Factors n=47

Omission of OTC medication or product

Prescribed by outside physician

Intentional nonadherence

OTC=over-the-counter n (%)

96 (51.6)

90 (48.4) n (%)

29 (61.7)

9 (19.1)

9 (19.1)

Although anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agents were the classes of medications found to be most often involved in discrepancies in this outpatient setting, medication discrepan cies reported in previous studies conducted in hospital settings involved different categories of medications. Coleman et al.’s study of post-hospital discharge discrepancies found that antico agulants (13%), diuretics (10%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (10%), and lipid-lowering agents (10%), were the 4 most commonly occurring medication classes involved in dis crepancies.

2 Cornish et al.’s evaluation of discrepancies upon hos pital admission found cardiovascular agents (26.6%) and central nervous system agents (25.9%) to be most commonly identified .1

The variation in identified medication classes may be the result of the differences in the populations studied. Both pre- and posthospitalization studies evaluated senior patients with high acuity, whereas our outpatient population represented a younger, less medically complicated group. A study that evaluated predictors of discrepancies in outpatient practice found through multivariate analysis that older age was strongly associated with the occur rence of medication discrepancies .8

Results of the present study show that discrepancies are evident in younger age groups as well, suggesting the importance of process improvement activi ties directed at building reliable systems that affect the accuracy of medication lists for all patients.

Classifying the causes of patient-generated discrepancies was a useful approach and highlighted the need to partner with the patient in order to arrive at medication list accuracy. OTC prod ucts initiated by the patient accounted for 61.7% of the patientgenerated discrepancies. A prospective study of 104 primary care outpatients conducted at the Mayo Clinic, that evaluated the prevalence of medication discrepancies in the EMR, also found that omission of OTC drugs from the recorded medica tion list was a common discrepancy.

9 In that study, a program of mailed letters reminding patients to bring medication informa tion to appointments, coupled with verification and correction of medication lists, was associated with a decrease in discrepancies from 89% to 66% of visits. Phase I of the Mayo Clinic study com pared the medication list recorded in the EMR with a reconciled medication list produced by a nurse telephone interview with the patient. Of the 147 OTC and herbal products reported as being taken by the patients, 87 (76%) were omitted from the EMR medication list.

9 Developing similar strategies for capturing this information from the patient would be valuable in addressing patient-generated discrepancies.

TABLE 4 Top 10 Discrepancies Categorized by

AHFS Therapeutic Class a (n=233)

Therapeutic Class

Anti-infective agents b

Anti-inflammatory agents c

Analgesics d

Vitamins

Anxiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics

Contraceptives

Antidepressants

Beta-adrenergic agonists

Supplements n (%)

33 (14.2)

33 (14.2)

29 (12.4)

23 (9.9)

15 (6.4)

15 (6.4)

13 (5.6)

9 (3.9)

9 (3.9)

Antiemetic

Total number of discrepancies in top 10 categories

5 (2.1)

184 (79.0) a Therapeutic categories are broad and include all dosage forms.

b Anti-infective agents include antibiotics, antifungals, and antiviral agents (e.g., azithroc mycin tablets, ketoconazole tablets, and clindamycin topical).

Anti-inflammatory agents is a broad therapeutic category that includes oral, nasal, topical, and rectal drugs (e.g., oral methylprednisolone tablets, montelukast tablets, mometasone nasal spray, fluticasone inhalation, desonide topical, and hydrocortisone suppositories).

d Analgesics include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, and opiate analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen tablets, celecoxib capsules, and acetaminophen/ codeine tablets).

AHFS=American Hospital Formulary Service

Process Improvement

The MDT methodology served as a useful qualitative guide for evaluating discrepancies and developing targeted means for reso lution. The finding that the greatest number of system-generated discrepancies resulted from expired medications being left active on the medication lists permitted the development of a targeted, systematic corrective action plan. An examination of the top 3

AHFS therapeutic classes showed the presence of many medica tions for which the length of therapy is known at prescribing; the simple addition of an order end date to the EMR would automate removal from the EMR medication list.

To aid this effort, an educational campaign was launched at

PAMC to encourage physicians to enter an appropriate end date to prescription orders when the length of therapy was predictable upon order entry. Chronic medications, which were rarely identi fied as discrepancies in our evaluation, were not to be given an end date. The information was presented to the Family Medicine physicians at a department meeting. As a process check, the

630 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

Sources and Types of Discrepancies Between Electronic

Medical Records and Actual Outpatient Medication Use percent of short-course azithromycin orders written with an end date was measured 30 days pre- and post-presentation. Before the presentation, 7 of 25 (28%) total orders of azithromycin con tained an end date. After the presentation the percentage rose to

16 of 23 (70%). Plans are under way to automatically populate the end date field for many medications.

As part of its “5 Million Lives Campaign,” the Institute for

Healthcare Improvement recommends encouraging patients to play a major role in ensuring that the medication list is kept up to date as they visit multiple providers in the outpatient setting.

10

Strategies for reducing patient-generated discrepancies have been explored by other medical groups.

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care conducts a comprehensive medi cation reconciliation program that involves direct pharmacist intervention with high-risk patients.

11 A similar program that uses pharmacists to conduct a comprehensive medication recon ciliation while a patient undergoes dialysis has been successful at the Dialysis Clinic Inc. in Kansas City, Missouri.

12

Limitations

First, our study was limited to a small sample of outpatients who telephoned an advice-line nurse to request assistance with relatively minor medical conditions. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to a broader outpatient population. Second, the nurse interview process relied on patient self-report as a “gold standard” against which the EMR was compared. Errors made by patients in reporting drug, duration, or dose, or by nurses using the protocol could have overstated the rate of discrepancy between the EMR and the patient-reported information. Lastly, because data extraction was conducted by one person, errors or biases could have affected the data collection process.

■■ Conclusions

Discrepancies in the outpatient setting were common and pre dominantly system generated. Establishing appropriate medica tion order end dates at the point of prescription order entry could eliminate 50% of the system-generated discrepancies in this study setting. Effective methods to improve medication list accu racy should address both system- and patient-generated discrep ancies. A “stretch goal” for all outpatient office settings should be to supply every patient with an accurate list of active medications that would improve patient safety throughout the continuum of patient care. The MDT methodology served as a useful qualitative guide for evaluating discrepancies and developing targeted means for resolution.

DISCLOSURES

The author reported no funding for this study and no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medica tion discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med .

2005;165(4):424–29.

2. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrep ancies. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1842–47.

3. Smith JD, Coleman EA, Min SJ. A new tool for identifying discrepancies in postacute medications for community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr

Pharmacother. 2004;2(2):141–48.

4. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW.

Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA . 2007; 297(8):831–41.

5. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospital ists. J Hosp Med.

2007; 2(5):314–23.

6. Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, Marchesano R, Etchells EE.

Frequency, type, and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. CMAJ . 2005;173(5):510–15.

7. McEvoy GK, ed. AHFS Drug Information 2005.

Bethesda, MD: American

Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2005.

8. Bedell SE, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, Glaser H, Gobble S, Young-Xu Y, et.al. Discrepancies in the use of medications. Arch Intern Med.

2000;160

(14):2129–34.

9. Varkey P, Cunningham J, Bisping S. Improving medication reconciliation in the outpatient setting . Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.

2007;33(5):286–92.

10. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

11. Bernstein L, Frampton J, Minkoff NB, et al. Medication reconciliation:

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care’s approach to improving outpatient medication safety. J Healthc Qual.

2007;29(4):40–45

12. Manley HJ, Drayer DK, McClaran M, Bender W, Muther RS. Drug record discrepancies in an outpatient electronic medical record: frequen cy, type, and potential impact on patient care at a hemodialysis center.

Pharmacotherapy . 2003:23(2):231–39.

Author

KATHLEEN B. ORRICO, PharmD, BCPS, is Health Sciences Assistant

Clinical Professor of Pharmacy, University of California, San Francisco,

School of Pharmacy; and Clinical Pharmacist, Palo Alto Medical

Foundation, Palo Alto, California.

AUTHOR CORRESPONDENCE: Kathleen B. Orrico, PharmD, BCPS,

Palo Alto Medical Foundation, 795 El Camino Real, Pharmacy Level A, Palo

Alto, CA 94301. Tel.: 650.614.3217; E-mail: orricok@pamf.org.

www.amcp.org Vol. 14, No. 7 September 2008 JMCP Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 631

R E S E A R C H

Prevalence and Humanistic Impact of Potential Misdiagnosis of

Bipolar Disorder Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder in a Commercially Insured Population

Siddhesh A. Kamat, MS; Krithika Rajagopalan, PhD; Ned Pethick, PharmD, MBA;

Vincent Willey, PharmD; Michael Bullano, PharmD; and Mariam Hassan, PhD

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Patients with bipolar disorder typically present to physicians in the depressed rather than the manic or hypomanic phase of illness.

Because the depressive episodes in bipolar disorder may be indistinguishable from those in major depressive disorder (MDD), misdiagnosis may occur.

OBJECTIVES: To estimate from administrative claims data and a telephone survey the prevalence of potential misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among patients with MDD and the humanistic (health-related quality of life

[HRQOL] and disability) effects associated with misdiagnosis in a managed care setting.

METHODS: Administrative claims data were used to identify patients with medical claims for MDD from a database of 9 million members of commercial health plans from 3 U.S. regions. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

(a) adults aged 18 years or older; (b) at least 2 medical claims, including a primary or secondary diagnosis of MDD: ICD-9-CM codes 296.2x (MDD, single episode), 296.3x (MDD, recurrent episode), or 311 (depressive disorder, not classified elsewhere) during an identification period from

January 1, 2000, through March 31, 2004 (study intake period); (c) at least

12 months of pre-index and 12 months of post-index plan eligibility; and

(d) active enrollment through March 31, 2005. The index date was defined as the date of the first claim for MDD during the identification period.

Patients with ICD-9-CM codes for bipolar disorder at any time throughout the study period (January 1, 2000, through March 31, 2005) were excluded from this cohort. This cohort was targeted for a telephone survey that was conducted from August 1 through October 30, 2006. From the telephone survey sampling frame of 5,777, a total of 1,360 interviews were completed for a response rate of 23.5%. Respondents were screened for potential bipolar disorder using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). The Medical

Outcomes 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12), Version 2, a widely used and validated instrument that assesses health-related functioning, and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), which measures depression-related disability, were administered to a convenience subsample of 112 survey respondents to collect HRQOL and disability information, respectively.

RESULTS: Of 1,360 adult patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of

MDD but without a medical claim for diagnosis of bipolar disorder,

94 (6.9%) screened positive for bipolar disorder on the MDQ. More patients with a positive screen for bipolar disorder reported lifetime histories of obsessive compulsive disorder (24.5% vs. 8.2%, P < 0.001), psychotic disorders or hallucinations (9.6% vs. 2.4%, P < 0.001), suicidal ideation

(61.7% vs. 29.4%, P < 0.001), and drug abuse (34.0% vs. 11.1%, P < 0.001) than did patients with a negative screen for bipolar disorder. In the subgroup of patients who completed the SF-12 and SDS, patients with a positive screen for bipolar disorder (n = 33) had lower scores (i.e., greater impairment) on the social functioning, role emotional, and overall mental component summary scales of the SF-12 than did patients with a negative screen for bipolar disorder (n = 79, P < 0.001), but did not significantly differ on the physical component summary scale. Patients with a positive screen for bipolar disorder on the MDQ were more likely than patients who screened MDQ-negative to report severe depression-related impairment

(scores of 7 and higher on the SDS scale) with work life (54.5% vs. 24.1%, respectively, P = 0.002), social life (66.7% vs. 39.2%, P = 0.008), and family life (66.7% vs. 34.2%, P = 0.002) on the SDS.

CONCLUSIONS: In this study of patients carrying medical claims for a diagnosis of MDD in their administrative claims data, approximately 7% screened positive for bipolar disorder on a validated self-report assessment instrument. Patients with MDD who screened positive for bipolar disorder reported poorer HRQOL and disability scores than did patients with MDD who screened MDQ-negative. These findings may encourage interventions for appropriate screening, diagnosis, and management of potentially misdiagnosed bipolar disorder patients.

J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(7):632-642

Copyright © 2008, Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. All rights reserved.

What is already known about this subject

• Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder is common. In a survey of support group participants diagnosed with bipolar disorder,

69% reported initial misdiagnosis by the first physician from whom they sought treatment, and misdiagnosed patients reported seeing a mean of 4 physicians before being diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

• Previous studies of the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder were conducted in the clinical/outpatient setting. However, the rate of misdiagnosis among commercially insured patients, who may be “healthier” than patients recruited from clinical/outpatient service centers, is unknown.

632 Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy JMCP September 2008 Vol. 14, No. 7 www.amcp.org

Prevalence and Humanistic Impact of Potential Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder in a Commercially Insured Population

B ipolar disorder, a chronic psychiatric illness with a variable course, affects between 1% and 4.4% of the U.S. popula tion 1,2 and costs more than $7 billion in direct medical costs and $38 billion in indirect costs (1991 values).

3 According to the World Health Organization, bipolar disorder was among the top 10 causes of disability in the world in 2000 4 and was asso ciated with significant impairment of a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) even after symptomatic recovery.

5,6

Patients with bipolar disorder suffer high rates of unemployment 7

(up to 60%) or occupational difficulties 8,9 (up to 88%), and twothirds of patients report difficult family relationships.

9 Moreover, misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder is common.

7,10 In Hirschfeld et al.’s survey of support group participants diagnosed with bipolar disorder, 69% reported initial misdiagnosis by the first physician from whom they sought treatment, and misdiagnosed patients reported seeing a mean of 4 physicians before being diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

7

Without proper treatment, the symptoms of bipolar disorder

(including suicide attempts) tend to increase in frequency and severity 11 and are less easy to manage with pharmacological intervention.

12 Accurate diagnosis necessitates a medical history from the patient and family or friends, 7 and the patient-rated

Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) has been shown to be a useful screening tool for bipolar disorder.

13-15 In particular, differentiation of bipolar disorder from major depressive disor der (MDD) is essential for the appropriate management of the patient’s condition, 16 and an analysis of administrative claims data found an association between undiagnosed bipolar disorder and higher total all-cause medical costs.

17

This study was undertaken to document the rate of positive screens for bipolar disorder among an MDD population in a managed care setting. The impact of misdiagnosis on HRQOL and depression-related disability was evaluated. Quantifying potential bipolar disorder misdiagnosis among the MDD popu lation may help to optimize the identification and therapeutic management of these patients and may result in better patient outcomes.

■■ Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of administrative claims, with cross-sectional diagnostic and HRQOL evaluations per formed on a subset of patients. The study used data from 3 geo graphically dispersed health plans located in the southeastern, western, and midwestern regions of the United States, consisting of approximately 9 million commercially insured members.

Patients enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid were not included in the study. The claims dataset included medical (inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room [ER] visits) and pharmacy encounters, as well as eligibility files. The study protocol and the survey instrument were sent to Quorum Review Inc., an independent institutional review board (IRB), for approval and to receive a Partial Waiver of Authorization under the terms of

What this study adds

• Using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), 6.9% of patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) screened positive for bipolar disorder.

• Patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder were less likely than MDQ-negative patients to be married (48.9% vs.

60.7%, respectively), and reported higher lifetime rates of highrisk behaviors, including suicidal ideation (61.7% vs. 29.4%), drug abuse (34.0% vs. 11.1%), and psychiatric symptoms, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (24.5% vs. 8.2%) and psychotic disorders or hallucinations (9.6% vs. 2.4%).

• Compared with patients with MDD who screened MDQnegative, those who screened positive for bipolar disorder were more likely to indicate depression-related impairment on the

Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) and had greater impairment in

3 SF-12 measures, including social functioning, role emotional, and the mental component summary scale.

the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to use patient-level data for purposes of contacting patients for the survey. The study protocol included involvement of an external vendor to conduct the survey, which was approved by the IRB. All researchers handling protected health information were autho rized to do so per company guideline and policies, and all study materials were treated with confidentiality.

Patient Identification

The study population was identified in 2 phases—first through examination of data from administrative claims, and then by telephone survey, conducted in a subset of patients (Figure 1).

Identification of Survey Sample

Adults aged 18 years or older with (a) at least 2 medical claims, including a primary or secondary diagnosis of MDD with dates of service between January 1, 2000, and March 31, 2004 (study identification period); (b) at least 12 months of pre-index and

12 months of post-index plan eligibility; and (c) active enrollment through March 31, 2005, were selected for the claims analysis.

The index date was defined as the date of the first claim for MDD during the identification period. Patients were required to have at least 2 medical claims for MDD because we wanted to select a patient population that had a chronic form of depression. MDD diagnostic codes were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM;

Table 1). Patients with ICD-9-CM codes for bipolar disorder at any time during the entire study period (January 1, 2000, through March 31, 2005) were excluded from this cohort.

www.amcp.org Vol. 14, No. 7 September 2008 JMCP Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 633