a psychopathological perspective

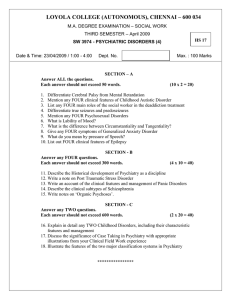

advertisement