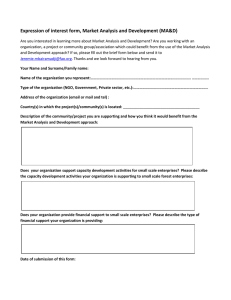

here - Social Entrepreneurship Network

advertisement