CSPI report - European Science Foundation

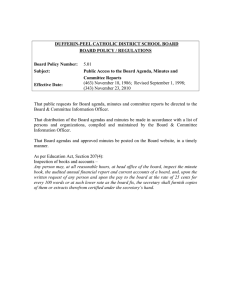

advertisement