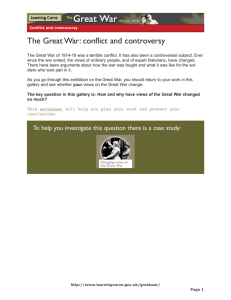

here - Chisenhale Gallery

advertisement