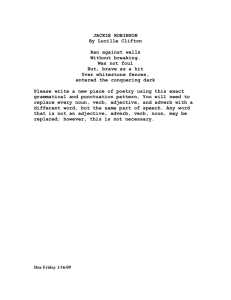

Writer`s Handbook Final Draft for Printer[1]

advertisement

![Writer`s Handbook Final Draft for Printer[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/018527936_1-8a26e440f648450c11f70d1ecbec8051-768x994.png)