Straddling the Color Line - OhioLINK Electronic Theses and

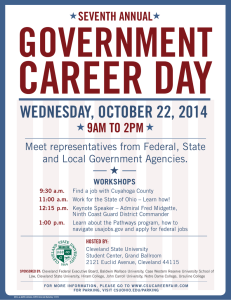

advertisement