CLEVELAND, OHIO (USA): THE TALE OF A SUPPLEMENTARY

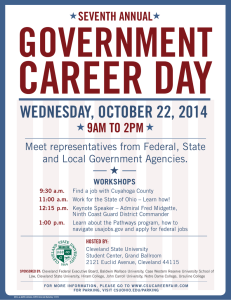

advertisement

CLEVELAND, OHIO (USA): THE TALE OF A SUPPLEMENTARY EMPOWERMENT ZONE W. Dennis Keating Professor and Associate Dean Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University 1717 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44115 USA Tel: (216) 687-2298 Fax: (216) 687-9342 E-mail: dennis@wolf.csuohio.edu Paper presented at the conference “Area-based initiatives in contemporary urban policy” Danish Building and Urban Research Institute and European Urban Research Association, Copenhagen, Denmark 17-19 May 2001 1 Preface This paper briefly describes and analyzes the Supplemental Empowerment Zone program in Cleveland, Ohio, USA during the period 1995-2000. It is intended to complement the paper being presented by Robin Boyle and Peter Eisinger entitled “Empowerment Zones: Much Ado About Something in U.S. Urban Policy”, which provides an overview of the Empowerment Zone program initiated in the United States in 1994-95 by the Clinton administration. I was the leader of an evaluation team that followed the Cleveland program for Abt Associates and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and is reflected in the as yet unreleased Abt report entitled “Interim Assessment of the Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities Program: A Progress Report”. The views of the author are not those of Abt Associates or HUD. 2 Introduction Cleveland, Ohio is located on the shores of Lake Erie. Once the sixth largest city in the United States, it has experienced a lengthy decline over the past half-century. From a peak population of 914,000 in 1950, this fell to a reported 478,000 in 2000. This loss of population reflects the loss of manufacturing jobs, the decline of the central business district, and the general pattern of a suburban exodus from central cities that continues in metropolitan Cleveland (Bier 1994; Hill 1994, 1999). All of these trends have resulted in devastated neighborhoods and high rates of unemployment and poverty, exacerbated by racial tensions (Chandler 1999; Coulton and Chow 1994). In 1967, Carl Stokes was elected mayor, becoming the first AfricanAmerican mayor of a major U.S. city. Since 1989, Michael White has been the city’s second African-American mayor. White and his immediate predecessor, following the lead of Cleveland’s corporate leadership, have given a very high priority to the redevelopment of the city’s downtown. The city’s “Civic Vision” plan emphasizes the downtown as an employment center featuring financial services, retail, and entertainment. The city has sought to become a regional convention and tourist destination. Over the past decade, this has led to the building downtown of three new sports stadia (Keating , 1997), the Tower City officeretail complex, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum, and the Great Lakes Science Center, all heavily-subsidized by public funds. The city also seeks to promote new housing downtown, as well as in its residential neighborhoods. As a result of these activities, Cleveland has called itself the “Comeback City”, seeking to reverse its negative image from the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969 and its financial default in 1978 during the turbulent administration of populist mayor Dennis Kucinich (Swanstrom, 1985). However, other data and realities overshadow this effort to paint Cleveland in its best light. In the 1990s, the city continued to lose jobs as businesses left despite the offer of incentives, most notably British Petroleum (formerly Standard Oil of Ohio)’s North American headquarters office from its tower on Public Square in the heart of the city. In the past few months, the city’s last major steel works declared bankruptcy for the second time. In March 2001, the experienced the third rupture of an aging main water pipe in fourteen months. The poverty rate was over 40 percent citywide and much higher in some neighborhoods in the 1990s. The public school system has long been in crisis, subject first to supervision by the federal courts, then a takeover by the state of Ohio, and more recently being transferred to the control of the mayor of Cleveland. Its students are mostly poor and minority, with a dropout rate exceeding half of those students entering and some of the lowest scores reported in the state on standardized tests. It was only recently released from a federal court cross-town busing order designed to overcome past racial segregation. The city remains highly segregated by race, with only a few of its neighborhoods having any significant racial and ethnic mix. Much of the city’s housing is below code standards and the metropolitan housing authority which provides federally-subsidized low-income housing has long been in crisis, with its housing racially segregated, much of it in disrepair, and with long waiting lists due to limited funding and the ending of new construction by the federal government(Chandler 1994). In response to some of these conditions, Cleveland is home to many neighborhood-based community development corporations (CDCs), which have attempted to reverse the decline of the city’s neighborhoods. With the 3 assistance of the city, local philanthropic foundations, corporations, and banks, these CDCs have an impressive record of building and rehabilitating housing for lower-income residents and assisting the city in improving neighborhood commercial districts and retaining employers. The Cleveland Housing Network, a citywide CDC coalition, has gained national recognition for its accomplishments (Krumholz 1997). 4 The Empowerment Zone Program: Original Application, Goals and Programs When the U.S. Congress enacted the Clinton administration’s Empowerment Zone (EZ) program in 1994, Cleveland applied. While it met the criteria for the six major empowerment zones to be selected, it lost in this competition to its larger Midwest counterparts – Chicago and Detroit. However, despite the Republican takeover of the U.S. Congress in the November 1994 election, Cleveland’s longtime African-American Congressman Louis Stokes (the late Carl’s brother), even though now in the Democratic minority and soon to retire, was able to exert his considerable influence with the Clinton administration to gain a consolation prize for Cleveland. Moreover, Los Angeles, assumed to an obvious winner in this competition to offset the destruction of the 1992 South Central riot, also was not named as an Urban EZ, with the award of a full 10-year grant of $100 million in direct assistance and tax credits for EZ employers hiring area residents. Nevertheless, HUD decided in late 1994 to name Cleveland and Los Angeles “Supplemental Urban Empowerment Zones (SEZ)” (Gale 1996: 139). What Cleveland received was only $3 million in direct aid and $87 million through HUD’s Economic Development Initiative (EDI), intended to promote economic development in distressed cities through grants and loans to area businesses, but not the tax credits awarded to the six urban EZs. Cleveland, therefore, had to adapt its original proposal in order to be able to use this funding in its EZ. Cleveland selected four east side neighborhoods to comprise its supplementary EZ (see attached map). Three – Fairfax, Glenville, and Hough – are primarily residential and the fourth – the Midtown Corridor – is almost entirely commercial and industrial (including major businesses, the Cleveland Clinic hospital and cultural institutions like the Cleveland Playhouse). The population of the three residential neighborhoods is almost entirely black and mostly poor (see Appendix 1). For example, Hough, the site of a major riot in 1966 (Gale 1996: 42-44), saw its population subsequently drop from a high of 65,000 in 1950 to under 20,000 in 1990 (Krumholz 1999: 93). Each of the four neighborhoods had a pre-existing CDC, supported by the city of Cleveland and their representatives on the Cleveland City Council – the Fairfax Renaissance Development Corporation (FRDC), the Glenville Development Corporation (GDC), Hough Area Partners in Progress (HAPP), and MidTown Cleveland. Cleveland’s strategy was to promote economic development in order to create jobs for EZ residents. To achieve this goal, it intended to use EDI funds to assist existing businesses located in the EZ and to attract other businesses to locate there, to use other funds for job training and placement assistance for unemployed residents, and to improve the housing, infrastructure and safety of the area to make it more attractive to both businesses and residents. One prominent example is the Church Square/Beacon Place mixed residential-commercial project in the heart of the EZ, where then Vice-President Al Gore unveiled the EZ initiative (Suarez 1999). To carry out the EZ programs, the city relied upon existing organizations, represented on a Citizens Advisory Council (CAC), to advise the city’s EZ office. These organizations included city agencies, other public institutions, and private organizations. This included a newly-initiated Cleveland Community Building Initiative launched by the Cleveland Foundation Commission on Poverty, operating in the Fairfax neighborhood. 5 In addition to HUD funds for economic development, the city also had its own programs and also hoped that a newly-opened community development bank (ShoreBank) located in the Glenville neighborhood would fund new enterprises employing EZ residents. The main innovations of the EZ program were a new loan program for small businesses and the introduction of a private security patrol in the EZ area, primarily serving businesses in the commercial districts. In addition to economic development, the other two major goals of the Cleveland EZ program were labor force development and community building. To achieve the former, the city contracted with several employment training/counseling agencies, most notably Job Match, established a new Center for Employment and Training (CET), and also expanded its own One Stop Career Center to the EZ area. Complicating the efforts to help unemployed and underemployed EZ residents to enter the work force was the 1996 enactment of federal welfare reform. As implemented in the state of Ohio, welfare recipients, primarily single women and their children, were limited in the future to only three years on welfare. This 3-year cut-off took effect in Cuyahoga County on October 1, 2001. This urban county, in which Cleveland is located, has the highest number of welfare recipients in the state of Ohio and a significant but unknown number live in the three residential EZ neighborhoods. Like the EZ program, Cuyahoga County embarked upon its own job training programs to assist recipients in finding work before they were cut off from welfare benefits. Further complicating efforts to find jobs for EZ residents in the economic boom times of the second half of the 1990s decade was the trend of new entry level jobs being created not only outside of the city of Cleveland but outside of Cuyahoga County. It has been estimated that fewer than 10 percent of the expected annual new entry-level job openings in Cuyahoga County will be in the city of Cleveland. Whether seeking jobs in the suburbs of Cleveland within Cuyahoga County or outside of the county, many EZ residents have a very difficult time in reaching those jobs without owning a car. Public transit to these suburban work places is very limited. An experimental van service provided for former welfare recipients is tiny. Cuyahoga County even initiated an experimental subsidy program to help welfare recipients with job-related transportation problems purchase used automobiles. 6 EZ Assessment: 1995-2000 The final interim assessment of Cleveland’s EZ was done in 2000, the midpoint of this 10-year program, as part of a national study of 18 cities. That report has not yet been released by HUD. As of 2000-2001, Cleveland has become a full-fledged EZ, with tax credits being made available to area businesses if they hire EZ residents. HUD has approved an expansion of the EZ area’s borders to allow more businesses to take advantage of these tax credits, should they choose to employ EZ residents. The first impediment to progress has been a regular turnover in leadership. During the period 1995-2000, the Cleveland EZ program had four different directors and all of the four CDCs in the EZ neighborhoods also had a change of leadership. In particular, HAPP in Hough had several directors and was suspended several times by the city’s Department of Community Development for alleged financial irregularities. The director of the city’s One Stop job training center was fired and ShoreBank went through several leadership changes. This turnover in leadership at all levels did not make for a smooth path in initiating and implementing innovative programs. The CAC also had several vacancies and did not play a very active role in either program direction or monitoring. Due to lack of funding, it and the EZ office failed to develop a 10-year strategic plan, as required by HUD. Therefore, the Cleveland EZ goals were mostly numerical. As of July 2000, the city reported to HUD that it had made $93 million in loans and $33 million in grants to EZ-located businesses, resulting in their investment of $89 million and the leveraging of a total of $235 million in private investment in the EZ area. The city projected providing financial assistance to 255 businesses and technical assistance to 350, with a little over 3,000 jobs for EZ residents created or retained resulting from these efforts. Without independent verification of these data, it is difficult to assess how much of the leveraged private investment can be attributed to the EZ program and the actual magnitude of the jobs claimed to be created. Job Match, a program of Vocational Guidance Services, reported training 2,371 EZ residents and placing 2,028 of them in jobs, some of them more than once. However, Job Match also reported a significant attrition rate increasing three and six months after placement. HUD did not require reporting on job retention by EZ residents. Job Match has an overall 10-year goal of job placement for 10,000 EZ residents but had placed only about 20 percent of that number after five years, rather than half. One deterrent to the use of this program is that the clients must take a mandatory drug test as a condition of participation. For this reason, many do not apply or drop out later. The city has not provided any additional drug counseling or treatment programs in the EZ. The CET program took awhile to organize. It only began training EZ residents in 1998 for welding and general machine work. It reported in September 1999 that 32 EZ residents had participated in these programs, with 25 graduates being placed in jobs. The city’s new One Stop career center opened in the EZ area in April 1998 but due to the controversy surrounding the firing of its director, information about its operations and impact were not available. The impact of Cuyahoga County’s job training programs for EZ welfare recipients also could not be determined because such data are not available. After five years, the overall impact of the EZ program on increasing employment and reducing poverty in its three residential neighborhoods is not impressive. At best, it is possible that as many as 5,000 residents 7 obtained or retained jobs, mostly low-wage entry jobs, whether in the EZ area or elsewhere. However, these data are hard to verify. It is also unknown just how many of those who did obtain jobs retained them after 3-6 months. Little is known about the activities of ShoreBank and its business incubator located in the Glenville neighborhood. To date, no EZ businesses have applied for tax credits for employing EZ residents. Many small businesses within the EZ, especially minority-owned, have not applied for or received EZ loans and grants. The reasons include their inability to develop business plans, past debts including unpaid taxes that make them ineligible, and reluctance to become involved in this government program. This is despite the availability of business development specialists through the four CDCs. And, there is no evidence of many new businesses developing or relocating in the EZ area, with the one exception of an assisted-living employer that relocated its office from a nearby suburb. The Midtown Corridor does have ambitious plans for the development of a bio-tech park but that remains in the future and even if it materializes it is not clear that it would employ that many unskilled or low-skilled EZ residents. The EZ can and does point to several new housing developments within the EZ sponsored by the three residential CDCs, with a total investment of $110 million. However, it is likely that they would have been constructed anyway using various public subsidies and private investment available to CDCs throughout the city. 8 Conclusion The goals of Cleveland’s EZ program were well intentioned. They included the creation of jobs sufficient to significantly reduce unemployment and poverty among its residents, almost all of whom are African-American, and to improve the physical, social and economic conditions of its four neighborhoods. The hope was that financial assistance provided to businesses, especially those in the Midtown Corridor with its many major employers, would spur their employment of residents, whose job readiness would be provided through a combination of existing and new job training and placement agencies located in or near to the EZ area. Instead of creating new entities, Cleveland chose to rely almost exclusively on existing agencies, both public and private, other than the creation of its own EZ office and the CET. As the above narrative recounts , many factors combined to frustrate the achievement of those goals over the first five years of this program. This was in spite of relatively prosperous economic times. Allowing for the necessary initial time for organization of EZ programs and considering the turnover in key leadership, the results are still disappointing. This is partly due to Cleveland’s forced reliance upon very limited economic incentives that require businesses to take out loans, rather than receive grants only, in order to receive assistance from the EZ programs. The absence of tax credits may have been a factor, although small businesses are unlikely to be able to take advantage of them anyway. Whether that many EZ residents will be able to obtain new jobs and improve their personal situation for long remains to be seen, especially if most of those jobs are outside the EZ. The cumulative losses in welfare benefits previously received by many of those EZ residents could largely offset the economic gains from the EZ programs, particularly since their jobs are mostly paying just above minimum wage ($6-7 per hour), may not provide health care, disability and retirement benefits, require the mothers to find and pay for private child care (which the city and the county have not provided on a major scale), and often involve transportation costs that are not subsidized by employers (and only temporarily, if at all, by public job assistance agencies). The EZ also has some fledgling programs aimed at improving public education for children in the EZ-located public schools but this has more long range than short term implications. Therefore, it must be said that Cleveland’s ambitious EZ program has not been sufficiently funded or effectively implemented to date so as to reach its fairly modest goals. With a new and conservative Bush administration now in office and a recent downturn in the U.S. economy, the prospects for increased federal assistance to areas like Cleveland’s EZ area do not seem bright. Finally, to the extent that the EZ program does provide jobs for EZ residents, it is unknown whether they will stay in its neighborhoods, even if improved with new housing and additional services like increased security. If the result would be the departure of the most energetic and able of the EZ residents, especially if their new jobs are located outside of the EZ area, it becomes doubtful as to whether the overall impact would necessarily be beneficial to the EZ residential neighborhoods if the poorest, most dependent and least employable residents are left behind. 9 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bier, Thomas E. 1994. “Housing Dynamics of the Cleveland Area, 19502000” in W. Dennis Keating, Norman Krumholz, and David C. Perry, eds. Cleveland: A Metropolitan Reader. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. Chandler, Mittie Olion. 1994. “Politics and the Development of Public Housing” in Keating, Krumholz and Perry. Chandler, Mittie Olion. 1999. “Race Relations in Cleveland” in David C. Sweet, Kathryn Wertheim Hexter, and David Beach, eds. The New American City Faces Its Regional Future: A Cleveland Perspective. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. Coulton, Claudia J. and Julius Chow. 1994 “The Impact of Poverty on Cleveland Neighborhoods” in Keating, Krumholz and Perry. Gale, Dennis E. 1996. Understanding Urban Unrest. London: Sage Publications. Hill, Edward W. 1994. “The Cleveland Economy: A Case Study of Economic Restructuring” in Keating, Krumholz, and Perry. Hill, Edward W. 1999. “Comeback Cleveland by the Numbers” in Sweet, Hexter and Beach. Keating, W. Dennis. 1997. “Cleveland: the Comeback City” in Mickey Lauria, ed. Reconstructing Urban Regime Theory: Regulating Urban Politics in a Global Economy. London: Sage Publications. Krumholz, Norman. 1997. “The Provision of Affordable Housing in Cleveland” in Willem van Vliet, ed. Affordable Housing and Urban Redevelopment in the United States. London: Sage Publications (Urban Affairs Annual Reviews 46). Krumholz, Norman. 1999. “Cleveland: the Hough and Central neighborhoods –Empowerment Zones and other Urban Policies” in W. Dennis Keating and Norman Krumholz, eds. Rebuilding Urban Neighborhoods: Achievements, Opportunities, and Limits. London: Sage Publications. Suarez, Ray. 1999. The Old Neighborhood. New York: the Free Press. Swanstrom, Todd. 1985. The Crisis of Growth Politics: Cleveland, Kucinich, and the Challenge of Urban Populism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Appendix 1: 1990 Profile of the Three Residential EZ Neighborhoods (Source: 1990 U.S. Census) Neighborhood Population %Black %Poverty Rate (Families) %Unemployment 10 Fairfax 8,973 98 50 26 Glenville Hough 25,845 19,715 97 97 39 55 24 30 11