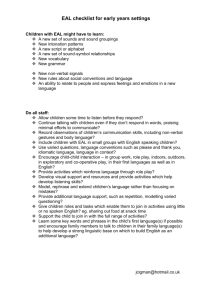

assessing EAL learners - Manitoba Education and Training

advertisement