Standards-Based Instruction Compendium of Resources

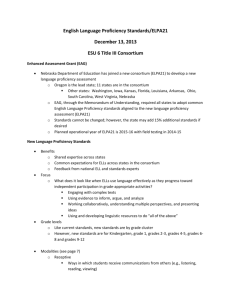

advertisement