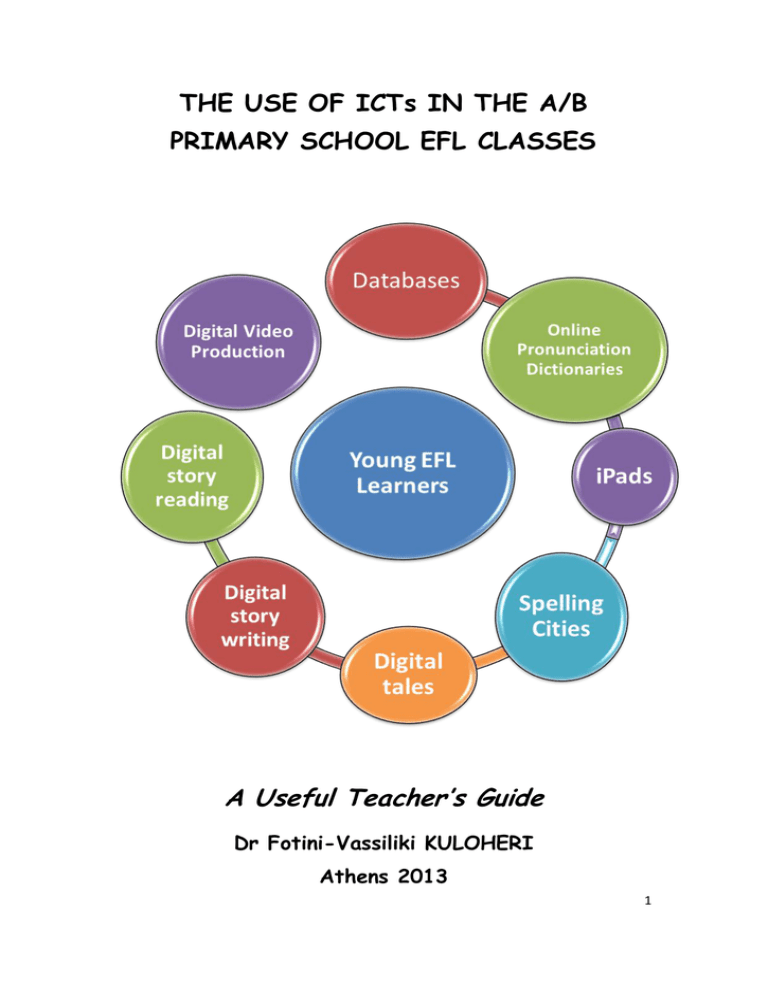

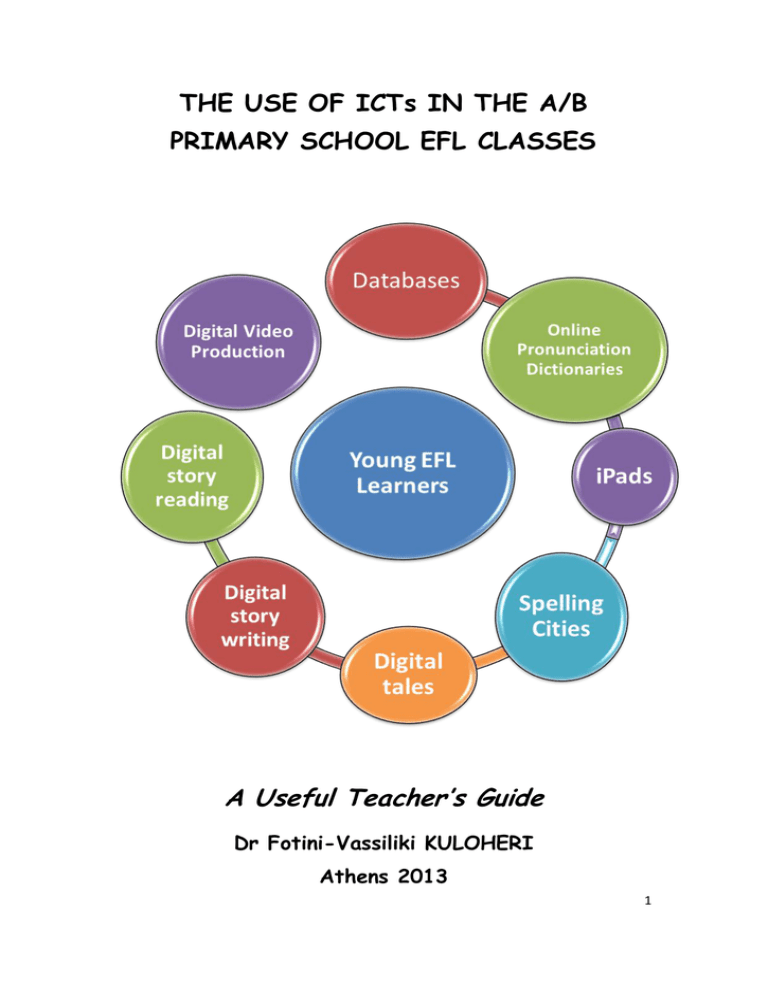

THE USE OF ICTs IN THE A/B

PRIMARY SCHOOL EFL CLASSES

A Useful Teacher’s Guide

Dr Fotini-Vassiliki KULOHERI

Athens 2013

1

2

The Use of ICTs

in the A/B Primary School EFL Classes:

A Useful Teacher’s Guide

3

4

The Use of ICTs

in the A/B Primary School EFL Classes:

A Useful Teacher’s Guide

Dr Fotini-Vassiliki Kuloheri

EFL teacher, Teacher trainer,

Materials designer

Athens 2013

5

ISBN 978-960-93-5478-3

© Fotini-Vassiliki Kuloheri 2013

Φωτεινή-Βασιλική Κουλοχέρη 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or

transmitted in any form without written permission from the author.

Απαγορεύεται η αναπαραγωγή, αντιγραφή, αποστολή, αναδημοσίευση του παρόντος

έργου με οποιονδήποτε τρόπο χωρίς προηγούμενη γραπτή άδεια της εκδότριας.

First published 2013 by

Fotini-Vassiliki Kuloheri, Athens, Greece.

Πρώτη έκδοση 2013 από

Φωτεινή-Βασιλική Κουλοχέρη, Αθήνα, Ελλάδα.

6

Dedicated to my very young school learners.

Who start learning English with a wide smile.

Whose eyes grow wide in anticipation of the

excitement EFL learning brings to them.

So that their smile does not fade out, and the

sun does not set in their minds.

7

8

Contents

Pages

1.

Introduction

1

2.

ICTs and TEYLs: Advantages of use

3

3.

Useful ICTs for A/B school EFL graders

7

3.1.

3.2.

4.

Vocabulary and spelling activities

3.1.1. Search databases

8

3.1.2. Vocabulary SpellingCity.com

9

3.1.3 Free Online English Pronunciation Dictionaries

10

Speaking

3.2.1. Online voice recorders

11

3.2.2. Digital Video Production

13

3.3.

Listening: Digital tales/stories

16

3.4.

Initial writing

19

3.5.

Initial reading

20

3.6.

iPads

20

3.7.

Overview: ICTs and learning goals

22

Important advice

4.1.

Before ICTs use

24

4.2.

During ICTs use

25

9

4.3.

References

After ICTs use

26

27

10

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to my school advisor Dr Thalia Hatzigiannoglou

(school years 2011-12, 2012-13), who played a crucial role in my first

training in the use of ICTs in the primary school EFL classes. Thalia

believed in my abilities, respected me deeply, and encouraged me to

pursue my self-development and share it with the wider professional

community.

I am also grateful to my dear EFL colleague Eleni Sotiropoulou (Med), who

devoted precious time to reviewing my book in a constructive way.

11

12

1.

Introduction

H

istorical,

scientific,

technological

and

socioeconomical

developments have led to the need for fast advancements in

the content and aims of educational systems worldwide, as

school education should adapt to life changes in order to prepare learners

for real life demands.

Most important of all, the Chaos Theory has led scientists to the

holistic, systemic approach of the complexity of world systems and subsystems and to the non-linear, interactive and interdependent relations

between them (Matsaggouras, 2002). Additionally, since the start of the

20th century Psychology and Educational Psychology have introduced a

series of changes in the perception of the nature of human beings and of

learning (ibid; William and Burden, 1997). In particular, they have

stressed the principle of wholeness that characterizes human perception

(Morphological Psychology) and the human soul (Child Psychology), the

active participation of human beings in learning processes through various

strategies that allow the understanding of the world (Constructivism),

and the importance of thoughts, emotions and feelings, learning needs and

self-evaluation (Humanism). More recently, emphasis has been given to

learning as the result of mediation of and interaction with others, who

have the same or different level of knowledge and skills (Social

Constructivism - William and Burden, 1997). Last, but not least, fastglobalized economies, technological advancements and the information age

across the globe call for digitally-literate citizens who can learn and take

responsibilities for their continuous personal learning development and

employability (The European E-learning Summit Task Force, 2001), and

1

for autonomous personalities capable of constantly renewing their

knowledge their knowledge, life attitudes and beliefs, and consequently of

responding successfully to the continuous adjustments of job markets

and social changes (Stamelos, 2010).

The above have left their imprint in current practices in Greek

school EFL education to very young learners (aged 5.5 to 7) worldwide.

So, they have forwarded the cross-curricular holistic approach to

teaching and learning in active and participatory learner-centred work

modes, which take into account learning aims, developmental profiles,

learning styles, intelligent types and personal reactions to classroom

stimuli, promote child socialization and intercultural awareness, and

exploit the advantages of ICT tools.

The following configuration depicts those key parameters of TEYLs

which contribute to the core target of EFL education, i.e. holistic child

development. One can identify below the key role that ICTs may play

towards the achievement of this aim.

2

2.

ICTs and TEYLs: Advantages of use

T

he term ICT (Information and Communications Technology)

embraces a wide range of services, systems, applications,

equipment and software, which allow for the transmission,

retrieval, editing, storage and in general the manipulation of information

(see

‘Information

and

Communication

Technology’

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_and_Communication_Technolog

y - accessed 14.09.13). It also comprises multimedia applications which

combine digital data in a variety of styles (e.g. text, graphics, image,

animation, sound and video).

The term stresses the role of the integration firstly of real-time

communication services (e.g. chatting, video conferencing, and data

sharing like interactive whiteboards) with non-real-time communication

services

(e.g.

voice

mail,

e-mail,

SMS),

and

secondly

of

telecommunications, computers, software and audio-visual and storage

systems.

Generally, the use of ICTs in the EFL classroom can improve the

quality of state primary school education by bringing EFL teachers and

learners closer to technological developments, facilitating teaching and

learning, and renewing teaching methods and techniques. More precisely,

classroom experience has shown that ICTs can be powerful educational

tools for teaching English to young learners (TEYLs) for the following

basic reasons. Many of these reasons are connected to the principles and

objectives

set

out

in

TEYLs

courses

(for

Greece,

see

PEAP1

http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/articles/programma-0 - accessed 14.09.13).

3

The variety of different ways in which ICTs can be used offer young

school children the opportunity to build up knowledge, understand

language input and use it as language output. They can also create

personal child time in class for these purposes. As a consequence,

individualized learning is supported, i.e. one of the most basic

educational principles at these ages (ibid).

ICTs can connect individual pupils with their EFL classmates or the

EFL learners of other classes/schools (e.g. through e-mails or chats).

This

is

especially

important

in

the

first

primary

classroom

environments, where children may often find themselves among new

cultures and new personalities. So, a second basic EFL learning

principle in TEYLs can be satisfied, i.e. the development of an

intercultural communication ethos (ibid).

Contexts are provided for the transfer of the children’s L1 social

literacy skills to EFL, the third basic TEYLs principle (ibid).

As tools that enhance spoken and/or written interaction, ICTs can

urge children to use their EFL knowledge for holistic purposes and so

get ready for real-life communication in English. Learning through

communication is achieved by offering rich language environments, in

which young learners have the continuous chance to participate in

language activities and use the target language as an interaction tool

with their classmates (Liaw, 1997).

From the large variety of contexts provided by ICTs, English teachers

can find the most suitable ones for their learners in terms of language

and content. A precise and comprehensible language context can exert

positive influence on young learners (Krashen, 1999), while subject

4

matter relevant to learners and close to their daily experiences can

increase their communicative ability (Arnold, 1999).

ICTs can forward learner-centered, participatory, collaborative and

exploratory learning, and the development of skills in the processing

of complex information in environments of authentic and multimodal

texts

(Educator’s

Guide/Οδηγός

Εκπαιδευτικού).

By

eliminating

antagonism in particular, technological applications can consequently

facilitate learning processes (Solomonidou, 1999).

ICTs can train children in basic computer and digital literacy skills

(Papaefthymiou-Lytra, 2004). Also, familiarization with the use of

computer technology decreases the stress caused by the contact with

e-tools children are initially not adequately acquainted with.

Child autonomy can be promoted, i.e. the child’s developing ability to

be responsible of their own learning (Dam, 2003). This is achieved

through training in strategies which make learning easier, faster, and

more effective, and which show children the way to comprehend the

learning process, evaluate it and adopt ways to determine it by

themselves successfully throughout their lives (ibid).

The children’s positive attitude towards EFL learning can be increased

as their interest in and motivation for learning are strengthened. As a

result, children can develop thinking skills at a higher level and better

vocabulary retrieval (Stepp-Greany, 2002).

Excitement is added to learning and the teacher’s work is made less

laborious (Stolkenkamp and Mapuva, 2010). Teaching becomes creative

5

and flexible, overcomes the limitations of school EFL curricula and

adopts advanced learning aims (Vernadakis et al, 2006).

So, turn on your equipment. Follow us in

our digital journey!

6

3.

Useful ICTs for A/B school EFL graders

T

his section is developed in accordance with the emphasis given

on lexis and the development of communicative skills during

TEYL courses (e.g. in Greece, Alpha English and Beta English

curricula

-

see

PEAP2 http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/articles/analytika-

programmata-ylis - accessed 30.09.13). Consequently, it covers vocabulary

development and consolidation, the development of speaking and listening

(for grades A and B), and the development of initial writing and reading

(additional focus of grade B).

The ICT tools suggested certainly do not comprise an exhaustive

list of the web tools available to EFL teachers for these purposes. They

are rather indicative of the possibilities ICTs open up to TEYLs for

motivating, effective and constructive lessons. Additionally, they are

suggested as successful means of promoting higher forms of thinking in

education like remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating

and creating (Bloom’s taxonomy of Learning Domains).

At the end of this chapter, you can find an overview of the

suggested tools in relation to the learning goals they can satisfy. This

Table can guide you in the selection of the most suitable ICT tool for

your lesson objectives.

Ts

I

C

7

3.1. Vocabulary and spelling activities

3.1.1.

Search databases

Search databases can be used in class to present and/or revise the

spoken and written form of word items, and forward their retention in

memory. They are an effective way of reinforcing the development of

early e-learning skills, as children can learn to apply their knowledge of

the English vocabulary, access web information by searching through

keywords, find examples of word meanings and evaluate what they find

(e.g. pictures). With A and B graders, it is most suitable to use the Image

search databases, as these promote the understanding of word meanings

through illustrations. It can be the English teacher and/or the learner(s),

who will use this tool.

Before using it, make sure you have first entered a web browser

like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer, Opera and Safari,

i.e. a software application for retrieving information resources on the

World

Wide

Web

(see

‘Web

browser’,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_browser - accessed 20.10.13). Then,

select ‘Images’/’Εικόνες’ on your browser, and use the bar at the top for

typing in your enquiries.

Image databases can be used in a variety of ways, so the following

ideas should not be regarded as an exhaustive list. Rather, they should be

approached as stimuli for more creative ideas that you yourself can come

up with. Indicatively, teachers can type in a word for presentation or

revision purposes. After pressing ’Enter’, the children will see a variety of

images related to this word. They can be asked to select the one they like

8

most and then to listen to their teacher pronouncing the word, relate it

mentally to the picture and repeat it. Alternatively, if a projector is

used, teachers can ask children to follow on the screen the letters they

type in and e.g. say which sound each letter represents and/or which word

it is. Then, children may be asked to draw the relevant picture on the

board and then to compare it with one of the respective database images.

Children can be encouraged to use the Image databases by

themselves too. For instance, they can type in words on their own (words

recently learnt or any they want), or words dictated by their English

teacher. The database can urge them to self-correction through the

message ‘do you mean (sun)?’ if a word is spelt wrongly, and through the

images that will appear. It will be a good idea too to ask children to

comment on images, like expressing thoughts, feelings, and emotions, as

they like being personally involved with pictorial elements.

A fun activity can be to ask them to type in their names in English.

Besides recalling the spelling, they can have fun by seeing what image

they come up with. Usually, images are unpredictable, which causes

laughter and creates a pleasant hilarious atmosphere in class. Images

corresponding to names can also be a good springboard for discussions on

e.g. historical topics.

3.1.2.

Vocabulary SpellingCity.com

This is an example of a free online tool to reinforce memory retention

and recall through the revision of the English alphabet letters and their

written forms, and of word spellings. It can facilitate the understanding

9

of minimal pairs by contrasting pronunciation, spelling and meaning. It is

also an effective tool for understanding the mechanics of reading in

English by analyzing sentences into words and words into letters and

sounds. Last, but not least, it exposes young EFL learners to authentic

English pronunciation and helps them evaluate their learning progress.

First, the teacher enters the selected word list (from three to ten

words). Then, five different kinds of activities are offered on this word

list. For example, children take turns to come to the computer, listen to

each word and type it in. At the end, they are given a word-by-word

result (i.e. correct spellings are ticked and false spellings are crossed out

and corrected in red). Alternatively, they can read the words silently,

select one, click on it, and listen to its pronunciation and to each letter of

its spelling. Or, they can search and circle the words in an alphabet grid,

unscramble letters, fill in a missing letter, and play spelling games like

‘Hangmouse’ and ‘Match the flashcards’ (i.e. a memory game in which they

click on word flashcards, turn them upside down, listen to and read the

word each flashcard represents while trying to find its match). Reading

activities may be to read silently four given words and select the one

they hear, or read the whole word list and put the words in alphabetical

order.

3.1.3.

Free Online English Pronunciation Dictionaries

Dictionaries of the sort (like e.g. ‘Howjsay’ http://www.howjsay.com/) are

offered online to help learners grasp and remember the English

10

pronunciation. Nevertheless, they can be a very good tool for practising

the English spelling too. Usually, these tools are very simple in use.

Children can type the word in the bar provided by the Dictionary,

submit it, mouse over it and hear it pronounced. Teachers may also wish

to make them aware of a more demanding process (suitable for B graders)

in which they browse through the alphabet, select the letter their word

starts with, scan the list of words that appears and select the word they

want. This mental procedure can familiarize EFL learners with the English

alphabet, urge them to become aware of sound-letter relations, and give

them training in initial English dictionary use, and in the development of

the reading subskill of scanning.

3.2. Speaking

3.2.1.

Online voice recorders

Free online voice recorders are services that help us record our own

voices and upload our messages on e.g. a blog, or a wiki. In TEYLs, they

can urge children to apply acquired knowledge in speaking in order to

communicate their own simple messages and to experiment with the

spoken language. At a second stage, they can also be given the chance to

evaluate themselves or each other’s performance by listening to the

recorded messages. Voice recorders can be very straightforward in use,

like

Vocaroo

(http://vocaroo.com/)

and

Soundcloud

(http://soundcloud.com/101/for), or a bit more demanding but also more

creative like Voki (http://www.voki.com/).

11

Vocaroo asks users to just click on a button to record. Soundcloud

allows the use of phone to record audio. But Voki gives us the tools to

create our personalized avatars too, and add voice to them. In addition to

these, Blabberize (http://blabberize.com/) could be used, which makes it

possible for young children to add a mouth to a picture their EFL teacher

has uploaded and to record their own voices to make the picture talk.

Services like the above firstly urge our young EFL learners to

revise vocabulary and experiment with the spoken language by actively

using words and very simple short phrases for communication purposes. In

Voki, children may practise their spelling too by selecting to write their

messages and then have them spoken (if they select to give a voice by

text-to-speech). Additionally, in order to select features to make their

own avatars, they are urged to read and understand the necessary key

words (i.e. ‘male/female’, ‘clothing’, ‘mouth’, ‘glasses’, ‘necklace’, ‘eyes’,

‘skin’, ‘hair’, ‘colours’). Classroom experience can confirm that young EFL

learners’ motivation is increased because they can play around with the

service, record and hear their own voices, and create the figures they

like.

Such kinds of services allow teachers and children to get engaged

in realistic communication characterized by information gap and a reason

for interacting (Littlewood, 1981). This is achieved by having their

messages posted on e.g. blogs, profiles, and/or websites, and by getting

feedback on them. For instance, if the teacher has posted a new message

for the children on the class wiki, then they will have a realistic reason to

read it and respond (provided they are trained to use the wiki, as

explained in the relevant section).

12

3.2.2.

Digital video production

This technology has already found a place in British primary schools

across different age phases, but there it is led by expert practitioners

and advisors (Potter, 2005). Although Greek EFL teachers may normally

not be among such practitioners or advisors that could lead such ICT

activity, TEFL training experience reveals that they are often eager to

try their hand at new tasks and at experimenting with their classes

successfully.

Digital video production (DVP) can be a difficult task for A and B

graders, but it is a perfect tool for training children in most of the

higher forms of thinking in Bloom’s taxonomy. More precisely, by

participating in the process of DVP, children apply the English lexis they

have learnt in appropriate contexts of use, compare it e.g. to antonyms,

relate it to images, and classify it under superordinates, thus

consolidating and expanding their vocabulary, practicing speaking, and

demonstrating the level of their learning. In addition, DVP can boost up

child self-esteem and increase self-confidence. It can also make children

aware of the actual technology, of the procedures followed and of its

advantages for self-expression (e.g. video editing elements like clip

ordering, transition between clips, use of sound effects, of narrative

voice and of soundtrack; Potter, 2005). It allows for creativity and

collaboration to take place in contexts that give rise to production and to

the understanding of the value of this production (Loveless, 2002). It

provides opportunities for evaluating the process experienced and the

final product. Last, but not least, it is very suitable for the application of

the cross-thematic approach to EFL learning as it presupposes the

13

merging of a variety of school subjects, like EFL learning, Music and

Theatre Education, Arts and Crafts, and Environmental Education.

Experimentations with Greek B graders in school EFL classes have

shown that learners as young as them can indeed succeed in taking an

active part in video authoring, provided that they are guided by their

English teacher closely, they are given enough time to get used to the

camera and try out different holds of it until their grip becomes more

stable, and they are allowed a number of experimental recordings until

they understand where the proper camera frame should be, which

buttons to press and when to press them.

To ensure success in the use of DVR, you need to prepare very well.

So:

Ensure access to a camera allowing recording digitally on a camera’s

hard disk, to a computer and to a free video editing web application.

‘Movie maker’ or Google ‘free video editing software’ could work;

however, you would rather find those applications that you can best

work with on your browser.

Recharge the camera beforehand, and familiarize yourself and your

young film makers with the very basic buttons of ‘record’, ‘stop’, and

‘rewind’.

Give out different roles to children, guide filmmaking closely through

a certain number of necessary steps, limit production to a short

sequence between 1 to 3 minutes the most, and set limitations on

content and/or actions (e.g. unacceptable actions beyond the planned

content should not be tolerated).

After getting prepared, you should determine the film making

steps; i.e.

14

1

Decide on the topic and content of the film (e.g. the weather today in

Athens, Thessaloniki and Crete, presented by three children in the

role of the weather broadcasters). Children will be motivated to

participate in decision-making if you ask for their opinion and

suggestions; nevertheless, remember to enforce behavior rules and

consequences and to set a time limit during these negotiations.

2 Decide on the component shots (e.g. first filming pictures of the

settings, like a picture of Athens, Crete and Thessaloniki, to introduce

the notion of the place, then filming the weather broadcasters talking

and then filming pictures relevant to the forecast, like umbrellas and

clouds to suggest the rainy weather).

3 Prepare the setting and the filming area. For instance, desks and/or

chairs may be added or taken away, a map of Greece may be fetched,

and groups of children may draw parts of the setting (e.g. tree leaves

to suggest autumn, air-blown hats to indicate windy weather, etc.).

4 Prepare the text for the broadcaster(s) (e.g. “Today it is raining in

Athens and it is windy. It is sunny and hot in Thessaloniki. …”).

5 Help the broadcaster(s) learn it. If the text is written with their

help, this will facilitate memory retrieval and effective production.

6 Position the broadcaster(s) and the filmmaker.

7 Have a number of trials before filming until the children feel

confident enough.

8 Have enough trial filming. Review it on location on the side panel of the

camera with the children, and invite their comments.

9 Make improvements and reshooting, if necessary.

10 Film the final.

15

11 Use the free editing application yourself to edit the film and produce

the finished product. But make sure you explain the stages to the

children as you do it (if there is enough space, or a limited number of

learners, you can encourage them to sit around you while doing the

job).

3.3. Listening:

Digital tales/stories

As multimedia technology is becoming more and more sophisticated, there

is growing interest in its use for language learning purposes, and in the

combination of the visual and auditory information in listening material

(Verdugo and Belmonte, 2007).

The reiterative, visual and interactive nature of material like

digital tales/stories forward individualized EFL learning at one’s own pace

through one’s active involvement in the decoding and understanding of the

information while interacting with the material. Interaction involves

applying

and

evaluating

knowledge,

i.e.

selecting

responses

and

confirming/rejecting/modifying them. Materials of this kind also foster

“a high level of individual control” (ibid: 88), to help children learn the

language progressively and to facilitate reading comprehension in the long

run.

Regarding

children’s

listening

skills

and

literacy,

digital

tales/stories are proved to be very useful in their development because

at the early acquisition stage they offer contextualized, meaningful and

memorable new language, present vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation

(the three language systems) in meaningful contexts, convey language

16

messages, feelings and memories, and are distinctive ways of manifesting

cultural values (ibid). However, the key to the above advantages is their

careful selection and suitable use with young learners, especially in light

of the overwhelming quantity of digital material offered.

So, EFL teachers first have to ensure that the digital tales/stories

chosen for A/B class learners meet the following three criteria (Kuloheri

1996):

1

Communicative value, i.e. their potential to expose learners to the

visual and aural component of real-life spoken interaction. Visual

components of communication can be clues suggestive of place and

time of interaction, participants, paralinguistic features like postures,

facial expressions and gestures, and cultural elements like hair type

and body size. Aural components of communication can be authentic

English language, frequently repeated words, neither too easy nor too

difficult language level (but just ahead of EFL child competence),

neither too slow nor too quick pace of delivery, careful but not

distorted articulation, intonation patterns and tone of voice indicative

of attitudes and emotions, and clear unambiguous message quality.

2 Content

value,

i.e.

meaningfulness,

comprehensibility,

interest,

relevancy to children’s background knowledge and world experience

(e.g. relation to school subjects and own daily experiences) and

absence of violence.

3 Value of formal media features, i.e. characteristics of the visual and

auditory code of the material which are distinct from its content and

necessary as techniques to capture the children’s attention. So, from

17

the extended list of such features, EFL multimedia tales/stories for

young learners should comprise mainly attention-gaining devices (like

laughter, music, child voices, applause, sound effects, and short

scenes) because these can extend child attention during viewing and

listening, enlarge concentration span and discourage children from

missing language and content details necessary for comprehension.

After material selection, English teachers are usually faced with the ‘How

to use’ question. The answer to this can come from our experience with

exploiting stories with young EFL classes. TEYL courses (like PEAP in

Greece) may provide teachers with detailed plans on story use, so

processes of the sort will not be dealt with in this booklet. However, our

attention should be drawn on the need to exploit the visual, interactive

and reiterative nature of multimedia, and some of the features mentioned

under the selection criteria. So, the following advice can be taken.

Teach key vocabulary associated with oral instructions used in

multimedia, e.g. ‘click/don’t click on …’. Check that the whole class has

understood it and can recognize what it means.

Help the class revise known vocabulary used in the material, and teach

new vocabulary if necessary, before they have a go with it.

When the meanings of new words are clear from the actual material,

do not hesitate not to pre-teach them. Rather, draw child attention on

these words while using the tale/story, and ask them to exploit visual

and language clues to guess their meanings. More generally, In general,

draw their attention on features that guide understanding (e.g.

picture parts, colours, sizes, shapes, key words like ‘left/right’).

18

Ask the children to listen to and understand a simple instruction first

before they go on with the story by clicking on screen parts (Verdugo

and Belmonte, 2007).

3.4. Initial writing

Young EFL learners can benefit by accessing web tools for writing

messages/notes and for storytelling. Colourful pictorial elements, the

autonomous choice of scene features (like settings, heroes, etc.), and

especially the opportunity and challenge to create something in writing

make such web tools extremely motivating and effective for our A and B

EFL classes. As Whitehead has put it, “When children first learn to write,

one of the moments of greatest significance for them is the realisation

that there is something they can create that will stand in their place

when they are not there.” (in Potter, 2005).

Kerpoof (http://kerpoof.com/), as an example of an ICT tool for

story writing, allows learners to create animated movies, pictures, cards,

artwork and stories online. It involves creating with the help of given

features and adding simple speech bubbles to it.

Free online services like Lino (http://en.linoit.com/) and Padlet

(http://padlet.com/) can provide young EFL learners with attractive

platforms (in the form of canvas or walls) and ready-made notes to write

on. In Lino, children can learn to drag post-it notes on their canvas,

whereas in Padlet they only have to double-click on the wall. Then, they

can write short messages or notes, like e.g. ‘Today is my birthday.’, ‘Happy

Birthday, Kostas!’, ‘Hello!’, ’I love my pets’, ‘How are you?’, ‘I’m fine.’, etc.

19

They can also write short comments under photos you may have stuck on

their Lino canvas or they have learnt to select in Padlet, like ‘Big sun, hi!’,

‘That’s great!’/’Great!’, ‘A party’, ‘Sunny weather.’ etc.

3.5. Initial reading

For the purpose of helping young EFL learners recall knowledge about

vocabulary, and recognize letters, understand letter sequences as

meaningful words and word sequences as meaningful sentences, teachers

can access free websites that make easy English reading material

available. Starfall (http://www.starfall.com/) can be an indicative example

of such a site, which helps learners learn to read English by phonics. Its

materials start up with alphabet letters related to phonics and words

(e.g. ‘a’ - /æ/ - ‘apple’), and gradually take children to minimal pairs (e.g.

‘can’, ‘fan’, pan’, ran’) and to online interactive books. Throughout the

materials children are exposed to relevant pictures which make meanings

very evident. The interactivity of such sites, their suitability for the

learning needs of our A/B EFL graders and the simplicity they retain in

content and use make it a very motivating and effective web-based tool.

For story selection, the criteria mentioned on pages 19-20 apply.

3.6. iPads

Since its launch, the use of this gadget has been gaining ground, to the

extent of being established as an educational learning tool in many

settings.

20

To the eyes of our A/B graders, iPads appear to be one of the most

exciting tools because they are part of the motivating mobile gadgetry of

their time and of their family life, and they seem easy to use due to their

portability. To the eyes of their English teachers, however, it may

currently seem a highly complicated business, perhaps redundant

compared to all the class work that needs to be covered, and/or an

unrealistic

purchase

under

the

financial

stresses

and

strains.

Nevertheless, nothing is complicated unless it is regarded as such.

Contrary to teacher beliefs like the above, iPads are a helpful, interactive

and engaging tool for the achievement of educational and language

learning aims, while a one-to-one relation between iPads and children in

class is not really necessary.

iPads can be used with both A and B graders. They comprise a

separate section in this booklet because, depending on the app (short for

‘application’), they can encourage learning in more than one aspects.

Namely, they can support the development of listening, reading and/or

speaking skills, help children revise and consolidate the alphabet and

vocabulary (e.g. shapes, colours, numbers, animals, commands), raise

awareness in children of the right pronunciation, and enhance the

development of their fine motor skills. Learning takes place in fun ways

through child interactions with engaging animations, sound effects, singalong-songs, stories, games and activities. Self-confidence is instilled in

learners, and their positive attitude to early EFL school learning is

increased.

The children just need to learn to touch or tap on the screen or on

the keyboard, or tilt the device. They also need to get familiar with the

21

most basic keys (the ‘play’, ‘rewind’, ‘forward’, ‘stop’, ‘record’ and ‘pause’

keys will be enough for the two first school grades). If certain children in

your class have played around with an iPad, then they can be involved in

peer scaffolding by showing to their classmates how the gadget works.

They can do ‘listen-and-do’ and ‘read-and-do’ activities, listen to

and sing songs, hear sounds (and e.g. recognize the right animal), listen to

stories and make story characters bounce around the screen, dance along

while listening or singing, record themselves saying something in English

(e.g. short dialogues/monologues) or record their own speech on selected

characters. In certain apps, they can even create their own short simple

imaginative stories.

You will be one of the luckiest ones if nearly all the children can

bring an iPad from home. In this case, they can work individually.

Otherwise, they can share in pairs or groups. The classroom use of iPads

makes it necessary that you have downloaded free iPad applications in

their gadgets first. There are several of them on the Internet, so just

search for ‘free iPad apps for toddlers/children’. It is very interesting

that you can also gain access to free apps for children with special

learning needs, so in this case iPads can set individual learning

environments for differentiated learning.

3.7. Overview: ICTs and learning goals

The following Table can provide an easy access to the relation

between

ICTs

and

TEYLs

learning

goals

22

ICTs

English language

system

Vocabulary

Search databases

Vocabulary

Spellingity.com

Free online

English

pronunciation

dictionaries

Online voice

recorders

Digital video

production

Digital

tales/stories

Digital

Kerpoof

writing

Lino

Padlet

Digital story

reading

iPads

1

S : Speaking

√

√

Pronunciation

Communication skills

S1

L

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

R

W

Remembering

Understanding

Applying

Analyzing

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

L : Listening

√

Synthesizing

√

√

R : Reading

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

Evaluating

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

Bloom’s taxonomy

√

√

√

√

√

√

W : Writing

23

4.

Important advice

4.1. Before ICTs use

Effective use of ICTs with young EFL learners must primarily mean

thorough preparation!

Make sure you have practiced using the ICT tool before the children

use it.

Prepare the computer lab before your lesson.

Are the computers, the projector and all other necessary

equipment working?

Is the screen set?

Are there enough chairs for the children?

Have you downloaded the tools on all the desktops?

Prepare a short clear list of the DOs and DON’Ts, stick it on the wall

and go through it with your pupils before each lesson starts. Ask them

to suggest and decide on the consequences and rewards to be set for

respectively insistent negative and positive behaviors.

Make a principled lesson plan. Think about aim(s), objectives, steps,

work modes, materials, and timing.

Steps may be differentiated, as kids can work in pairs or small groups,

and may be given different tasks to perform.

Individual work and pairs usually work best. Re. pairing, consider it

carefully. Some pairs perform better when they find themselves away

24

from best friends or worst enemies. If you like group work, try to

keep groups small. Sharing tasks and/or materials is still difficult at

these ages.

Keys on keyboards may have both Greek and English letters. Insist on

attracting their attention to the Roman alphabet, so that they get less

and less distracted by the Greek letters.

Explain the aims of each activity (i.e. what the kids will do and the

reason(s) why).

Ask elicitation questions to make sure they have understood. Involve

as many children as possible at this stage.

Then, give out the handout (if there is one), go through the task and

the task format. Go through the use of the keyboard keys the kids will

need

to

press

(e.g.

delete/backspace/enter/space/comma,

up/down/left/right keys, store), and revise basic desktop instructions

(e.g. in the Word document or the painting programme).

4.2. During ICTs use

After preparing thoroughly, remember to handle task-on procedures

carefully.

Let the kids do the task by themselves first.

Keep going around the class to see how they are performing. This can

provide an eye to e.g. each kid’s developmental route and learning

25

needs, the effect(s) of your planning, your task design, and the task

level.

Besides teacher scaffolding, encourage peer scaffolding too.

Be as discrete as you can; kids may feel worried, assessed and/or

inhibited.

Discourage antagonism and encourage cooperation as a means towards

socialization, self-balance, and self-discipline.

Take photos of this stage, as you may need them when constructing

your blog or collaborative wiki page. However, first get the children’s

informed assent, and their parents informed and signed consent.

4.3. After ICTs use

Every task requires a finishing touch, to ensure positive child attitude to

the learning medium, the learning activity and the learning outcome.

Make sure the kids’ work is saved.

Praise all the class.

Ask kids to talk about feelings and thoughts. Invite their suggestions

for procedural improvements.

In the next lesson, revise what they did last time to establish links

between sessions and coherence in your teaching. If possible, devote

some time to show the kids’ work on e.g. a wiki.

26

Resources

Arnold, J. (Ed.). (1999). Affect in language learning. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Bloom’s

Taxonomy

of

Learning

http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html

Domains

-

accessed

The

teacher’s

06.10.13.

Dam,

L.

(2003).

‘Developing

learner

autonomy:

responsibility.’ In David Little, Jennifer Riddley and Ema Ushioda

(eds.), Learner autonomy in the foreign classroom, Trinity College

Dublin: Authentik, pp. 135-146.

[Educator’s Guide in the application of the EPS-XS. 5. The Internet in the

subject of the foreign language] Οδηγός του εκπαιδευτικού για την

εφαρμογή του ΕΠΣ-ΞΓ. 5. Το Διαδίκτυο στο μάθημα της ξένης γλώσσας

http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/xenesglosses/guide_kef5.htm,

accessed

18.06.2003.

Information

and

Communication

Technology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_and_Communication_Tech

nology, accessed 14.09.13.

Krashen, S. (1999). Three arguments against whole language and why they

are wrong. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Kuloheri, F. V. (1996). ‘Criteria for the Selection of Primary Video

Material

for

EFL

Purposes’.

NELLE Conference Proceedings,

Zaragoza, Spain, 104-107.

Liaw, M.L. (1997). ‘An analysis of ESL children's verbal interaction during

computer book reading’, Computers in the Schools, 13 (3/4), 55-73.

27

Littlewood,

W.

(1981).

Communicative

Language

Teaching.

An

Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Loveless, A. (2002). Literature Review in Creativity, New Technologies

and Learning, 36, Bristol: NESTA Futurelab.

Matsaggouras, H. (2002). The cross-thematic approach in school

knowledge. 2nd ed. Athens: Gregoris. [Ματσαγγούρας, Η. (2002). Η

Διαθεματικότητα στη Σχολική Γνώση. 2η έκδοση. Αθήνα: Γρηγόρης.]

Papaefthymiou-Lytra, S. (2004). “Technology and the new foreignlanguage learning environment in contemporary Europe: Learning

conditions”. In B. Dendrinou and B. Mitsikopoulou (eds). Policies of

linguistic pluralism and foreign-language education in Europe. 1st

edition. Athens: Metaichmio, pp. 305-312. [Παπαευθυμίου-Λύτρα, Σ.

(2004). «Η τεχνολογία και το νέο ξενόγλωσσο μαθησιακό περιβάλλον

στην σημερινή Ευρώπη: Μαθησιακές συνθήκες.» Σε Β. Δενδρινού και Β.

Μητσικοπούλου

(Επιμ.).

Πολιτικές

γλωσσικού

πλουραλισμού

και

ξενόγλωσση εκπαίδευση στην Ευρώπη. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Μεταίχμιο, σσ.

305-312.]

PEAP1

http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/articles/programma-0,

accessed

14.09.13.

PEAP2 http://rcel.enl.uoa.gr/peap/articles/analytika-programmata-ylis ,

accessed 30.09.13.

Potter, J. (2005). “ ‘This brings back a lot of memories’ - A case study in

the analysis of digital video production by young learners.",

Education, Communication and Information, 5(1), 5-23.

Solomonidou, H. (1999). Educational technology. Means, materials:

teaching use. Athens: Kastaniotis. [Σολομωνίδου, Χ. (1999).

28

Εκπαιδευτική

Τεχνολογία.

Μέσα,

υλικά:

διδακτική

χρήση

και

αξιοποίηση. Αθήνα: Καστανιώτη.]

Stamelos, G. (2010). ‘Society of knowledge and life-long learning:

Inconsistencies and deadlocks Or The way to social outburst.” In N.

Papadakis and M. Spyridakis (eds), Job market, training, life-long

learning and occupation: Structures, institutions, and policies.

Athens: I. Sideris, pp. 219-242,. [Σταμέλος, Γ.(2010). “Κοινωνία της

γνώσης και δια βίου μάθηση: αντιφάσεις και αδιέξοδα Ή η πορεία προς

την κοινωνική έκρηξη.” Στο Ν. Παπαδάκης και Μ. Σπυριδάκης (επιμ.),

Αγορά εργασίας, κατάρτιση, δια βίου μάθηση και απασχόληση: Δομές,

θεσμοί και πολιτικές, Αθήνα: Ι. Σιδέρης, σσ: 219-242.]

Stepp-Greany, J. (2002). ‘Student perceptions on language learning in a

technological environment: Implications for the new millennium.’

Language, Learning and Technology, 6(1), 165-180.

Stolkenkamp, J., and Mapuva, J. (2010) ‘E-Tools and the Globalised World

of

Learning

and

Communication’,

Contemporary

Educational

Technology, 1(3), 208-220.

The European E-learning Summit Task Force. (2001). The European

eLearning

Summit.

Available

at

http://ec.europa.eu/education/archive/elearning/summit.pdf .

Verdugo, D. R. and Belmonte, I. A. (2007). ‘Using Digital Stories to

Improve Listening Comprehension with Spanish Young learners of

English’, Language Learning and Technology, 11(1), 87-101.

Vernadakis,

N.,

Avgerinos,

A.,

Zetou,

E.,

Giannousi,

M.

and

Kioumourtzoglou, E. (2006). “Learning through multimedia technology

– Promise or reality?” Inquiries into Physical Education and Sports,

4(2), 326-340. [Βερναδάκης, Ν., Αυγερινός, Α., Ζέτου, Ε., Γιαννούση,

29

Μ., και Κιουμουρτζόγλου, Ευθ. (2006). «Μαθαίνοντας με την τεχνολογία

των πολυμέσων – Υπόσχεση ή πραγματικότητα;» Αναζητήσεις στη

Φυσική Αγωγή και τον Αθλητισμό, 4(2), 326-340.]

Web browser: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_browser , accessed

20.10.13.

William, M. and Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for Language Teachers.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

30

31

‘The use of ICTS in the primary A/B EFL school classes: A useful

teacher’s guide’ will be especially valuable for teachers who work with

very young EFL learners, as well as teacher trainers and tutors at

Certificate, Diploma, Master’s and PhD programmes that have a strong

practical teaching component. It combines both theory and practice;

however. its practical aspect is mostly evident. Its language is simple, so

that it can be used for self-learning purposes too.

ISBN 978-960-93-5478-3

32