The Place of Environmental Theology - CEBTS

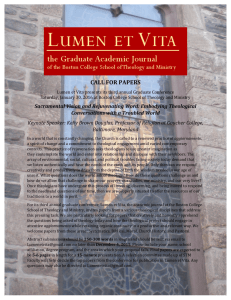

advertisement