eipascope

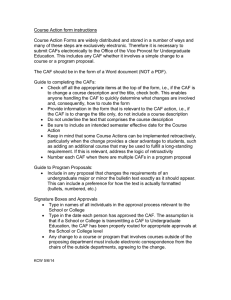

advertisement