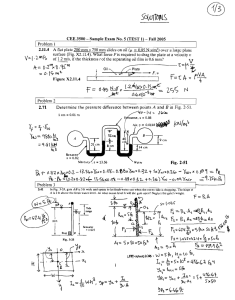

- ASU Digital Repository

advertisement