John Adams`s Views on Citizenship - Massachusetts Historical Society

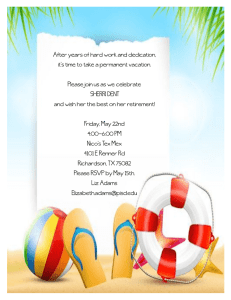

advertisement