TrainEd

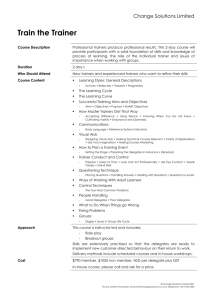

advertisement