The economics of quality-equivalent store brands

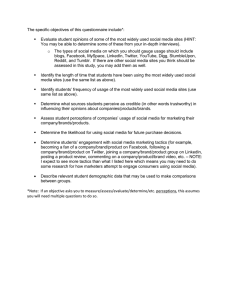

advertisement