vol. 166, supplement

the american naturalist

october 2005

Genetic Correlations with Floral Display Lead to Sexual

Dimorphism in the Cost of Reproduction

Lynda F. Delph,* Janet L. Gehring,† A. Michele Arntz,‡ Maureen Levri,§ and Frank M. Freyk

Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

47405

Online enhancement: table.

abstract: In dioecious plants, females typically invest more biomass in reproduction than males and consequently experience stronger life-history trade-offs. Sexual dimorphism in life history runs

counter to this pattern in Silene latifolia: females acquire less carbon

and invest more biomass in reproduction, but males pay a higher

cost of reproduction. The species is sexually dimorphic for many

traits, especially flower number, with males producing many, small

flowers compared to females. We tested whether the cost of reproduction is higher in males because flower number, which we presume

to be under sexual selection in males, is genetically correlated with

traits that would affect life-history trade-offs. We performed artificial

selection to reduce the sexual dimorphism in flower size and looked

at correlated responses in ecophysiological traits. We found significant correlated responses in total vegetative mass, leaf mass, leaf

thickness, and measures of CO2 exchange. Individuals in the manyand-small-flowered selection lines did not grow as large or invest as

much biomass in leaves, and their leaves exhibited an up-regulated

physiology that shortened leaf life span. Our results are consistent

with the hypothesis that genetic correlations between floral display

and ecophysiological traits lead to a higher cost of reproduction for

males.

Keywords: artificial selection, correlated responses, dioecy, genetic

correlations, sexual selection, Silene latifolia.

* Corresponding author; e-mail: ldelph@indiana.edu.

†

Present address: Department of Biology, Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois

61625; e-mail: jgehring@bumail.bradley.edu.

‡

E-mail: amknott1@hotmail.com.

§

Present address: Division of Math and Natural Sciences, Penn State–Altoona,

3000 Ivyside Park, Altoona, Pennsylvania 16601; e-mail: mal24@psu.edu.

k

Present address: Department of Biology, Colgate University, 13 Oak Drive,

Hamilton, New York 13346; e-mail: ffrey@mail.colgate.edu.

Am. Nat. 2005. Vol. 166, pp. S31–S41. 䉷 2005 by The University of Chicago.

0003-0147/2005/1660S4-40685$15.00. All rights reserved.

Life-history theory states that competition among various

activities within an individual can lead to life-history tradeoffs such as a cost of reproduction (Gadgil and Bossert

1970). Moreover, sex-specific differences in the cost of

reproduction can lead to sexual dimorphism in life history

(Trivers 1972; Bell 1980). Sexual dimorphism in life history

is a well-researched phenomenon in dioecious plants,

which have separate male and female individuals. Lloyd

and Webb (1977) first suggested that females should pay

a higher cost of reproduction than males because females

have a greater level of investment in reproduction. Indeed,

comparisons of multiple dioecious species show that

higher reproductive effort by females often is associated

with less growth, higher photosynthetic rates, delayed or

less frequent reproduction, earlier death, and spatial segregation, with males more frequent in low-resource sites

(Delph 1999; Obeso 2002). There are, however, exceptions

to this general pattern that are contrary to the idea that

investing more in reproduction will necessarily lead to a

higher cost of reproduction.

Silene latifolia is one such species whose pattern of sexual dimorphism in life history runs counter to the expected

pattern. In S. latifolia, males suffer greater life-history

trade-offs than females even though females acquire less

carbon and allocate more biomass to reproduction (Gross

and Soule 1981; Gehring and Linhart 1993; Gehring and

Monson 1994; Delph and Meagher 1995; Laporte and

Delph 1996). For example, males are smaller in both vegetative and total biomass and are less tolerant of high

density and limiting nutrients (Lawrence 1963; van Nigtevecht 1966; Lovett Doust et al. 1987; Gehring and Linhart

1993; Delph and Meagher 1995; Delph et al. 2002). Moreover, there is evidence that males die at a younger age than

females (Lovett Doust et al. 1987; Carroll and Mulcahy

1993; Gehring and Linhart 1993; Taylor 1994). Taken together, these results indicate that males exhibit a higher

cost of reproduction.

The hypothesis we set out to test is whether the cost of

reproduction is higher in males of S. latifolia because of

genetic correlations between a trait under sexual selection

(flower number) and traits that affect life-history trade-

S32 The American Naturalist

offs (allocation and physiology). Most differences between

the sexes are thought to arise at least initially from sexual

selection, which acts through differences in reproductive

success caused by competition for mates (Darwin 1871).

Sexual selection is usually considered distinct from viability selection because it operates specifically through variation in mating success and often opposes the action of

viability selection (Arnold 1985). An example of this tension between sexual and viability selection comes from

studies of marine iguanas, in which large individuals of

both sexes suffer from high mortality when food availability is low (Laurie and Brown 1990a, 1990b; Wikelski

and Trillmich 1997). Nevertheless, large males, but not

females, are strongly selected for via increased mating success and, as a consequence, there is sexual dimorphism in

body mass, with males being twice as heavy as females

(Wikelski et al. 1996; Wikelski and Trillmich 1997).

In S. latifolia, there is extreme sexual dimorphism in

flower production, with males producing as many as 16

times as many flowers as females (Meagher 1992; Laporte

and Delph 1996; Delph et al. 2002, 2004a). High flower

production is likely to have been sexually selected in males

but not in females (Delph et al. 2002, 2004a). Evidence

for this is fourfold. First, pollinators prefer plants with

large floral displays in this species (Shykoff and Bucheli

1995), and higher flower production leads to higher siring

success (F. M. Frey and L. F. Delph, unpublished data).

Second, flower number is the most sexually dimorphic

trait, and the extent of sexual dimorphism in other traits

depends on their correlation with flower number (Delph

et al. 2002). Third, flower size is highly negatively genetically correlated with flower number and is also highly

sexually dimorphic, with males making flowers that are

smaller in dimension and mass than those on females

(Carroll and Delph 1996; Meagher 1999; Delph et al. 2002,

2004a). Finally, although larger staminate flowers do not

produce more pollen per flower, there are more ovules in

larger pistillate flowers (Delph et al. 2004a). Hence, in

terms of size versus number, a male can make more pollen

by making more flowers but not by making larger flowers,

whereas a female can make more ovules by keeping flower

size large. Consequently, sexual selection in S. latifolia is

predicted to favor sexual dimorphism in flower display,

with males producing large numbers of small flowers and

females producing smaller numbers of relatively large

flowers. If flower size and number are genetically correlated with morphological and physiological traits that are

consequential for life-history trade-offs, then the production of elaborate floral displays by males could lead to

their higher cost of reproduction.

Artificial selection is a straightforward and powerful way

to test for genetic correlations among traits (Schluter 1988;

Conner 2003). Traits that are genetically correlated with

one under selection will show a correlated response in

proportion to the strength of selection applied and the

magnitude of the genetic correlation (Lande 1979; Arnold

1992, 1994; Schluter 1996). Therefore, to test the hypothesis that flower production is genetically correlated with

traits imposing life-history trade-offs, we performed

artificial-selection experiments to alter flower size. We

found a strong response to this selection and a strong

correlated response in flower number, indicating the presence of a flower size/number trade-off (Delph et al. 2004a).

Our selection took the form of reducing the sexual dimorphism in flower size (i.e., we selected for large flowers

in males and small flowers in females), but because of a

high between-sex correlation for flower size (Meagher

1999; Delph et al. 2004a), we were also able to expand the

sexual dimorphism in flower size and number. We capitalized on these experimentally altered patterns of dimorphism in flower size and number to test for correlated

responses in a host of morphological, allocation, and physiological traits.

Our intention was to look at correlated responses in

traits that could affect life-history trade-offs. Hence, we

measured allocation traits, with the prediction that individuals producing a relatively large number of flowers

would not be able to allocate as much biomass to vegetative

structures, such as leaves. In addition, we measured leaf

physiological traits, with the prediction that manyflowered individuals would have an up-regulated physiology that would cause them to have lower leaf life spans

and higher carbon costs. Specifically, we predicted that

individuals with many small flowers would grow less overall, invest less biomass in leaves, have thinner leaves

(higher specific leaf area) with lower longevity, have higher

stomatal conductance, and have higher photosynthetic,

transpiration, and dark respiration rates than individuals

with few large flowers. Overall, our results are consistent

with the hypothesis that sex-specific differences in the cost

of reproduction associated with flower production have

led to sexual dimorphism in life history.

Material and Methods

Study Species

Silene latifolia (Caryophyllaceae) is a dioecious, short-lived

perennial that typically flowers in its first year. The flowers

are white petaled and fragrant, open at night, and are

pollinated primarily by night-flying moths (Shykoff and

Bucheli 1995; Young 2002). These moths prefer plants with

large floral displays, that is, those with many open flowers

(Shykoff and Bucheli 1995). The populations used in this

study come from Giles County, Virginia. Although S. latifolia is not native to North America (Baker 1948), com-

Genetic Correlations and Sexual Dimorphism

parisons of multiple populations from Virginia and Europe

show that Virginian populations are intermediate for a

variety of floral and allocation traits (Delph et al. 2002).

S33

tent selection on the timing of reproduction or related lifehistory traits.

Correlated Responses

Artificial Selection

The selection lines used in the experiments described here

come from artificial-selection experiments to alter calyx

width. By performing artificial selection, we hoped to create lines whose means differed in flower size and also

flower number. We found that calyx width responded to

selection and that flower number showed a strong correlated response to this selection, revealing that it was

heritable and negatively genetically correlated with calyx

width (Delph et al. 2004a). Given the heritability of the

two traits and the flower size and number trade-off, we

were successful in creating lines whose means differed for

both flower size and number. The response to selection

on calyx width and correlated response in flower number,

together with a detailed description of the selection procedure, can be found in Delph et al. (2004a). Here, we

provide a brief description of the selection procedure.

Two completely separate sets of artificial-selection lines

were generated, which we will refer to as selection programs 1 and 2. Seeds for the experiments came from two

separate field populations, taken from 23 and 43 maternal

parents, respectively, for the two selection programs. Seeds

were grown in a greenhouse at Indiana University. In selection program 1, we created one line that favored females

with flowers whose calyx width was small, one control

line, and one line that favored males with flowers whose

calyx width was large. In the second selection program,

we created two replicates each of the small and large lines

and one replicate of the control line. Five generations were

grown for each selection program, which gave four bouts

of selection in each case. Selection program 1 ran from

1993 to 1998 and selection program 2 from 2000 to 2003.

We measured the calyx width of specific flowers each

generation (selection program 1: second through seventh

flowers to open; selection program 2: third through fifth

flowers to open). To create the line with flowers with small

calyces, we identified the six families with females that

produced flowers with the smallest calyx width in each

generation and reciprocally crossed a subset of their members to produce 30 new families for the next generation.

Likewise, to create the line with flowers with large calyces,

we identified the six families with males that produced

flowers with the largest calyx width and reciprocally

crossed a subset of their members. All plants were allowed

to flower before the selection of families was made. This

increased the amount of time it took to complete each

generation, but it was important to prevent any inadver-

In the last generation of both selection programs, we measured several traits to determine whether they showed a

correlated response to selection on calyx width. All traits

were measured in both selection programs, except where

noted (see table 1). Categories of traits included morphology, allocation, and physiology. Results on correlated

responses in flower number, petal limb length, flower

mass, and ovule or pollen number are reported elsewhere

(Delph et al. 2004a, 2004b).

In selection program 1, we did not have enough greenhouse space to grow all plants for 1 month after they began

flowering, so we randomly selected three plants per family

(two females and one male) to grow and measure for the

1-month-after-flowering data. A small number of additional plants were saved from each family to use as pollen

donors or for measuring stem respiration (see below), but

the rest were discarded. One of the two females per family

had all of it flowers pollinated (randomly chosen), and the

other female from each family was left unpollinated. Flowers open in the evening, and pollinations were made the

following morning by rubbing dehisced anthers from two

or three flowers of an unrelated male across the stigmatic

papillae. This allowed us to compare pollinated and unpollinated females. Data from the two groups were combined for analysis of specific traits only when there were

no significant differences between them.

Measurements of leaf physiology were always made on

the leaf one node down from the node containing the first

flower to open and used an open gas exchange system,

the LI-6400 (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Only undamaged, nonsenescent leaves were measured. In selection program 1,

a tube was run outside one of the greenhouse windows

for the incoming CO2 (hence, the concentration varied

slightly), and in selection program 2, CO2 concentration

was maintained at 400 mmol mol⫺1. Measurements were

taken at flowering or 1 month after flowering began for

each plant, as noted. After the 1-month-after-flowering

measurements, the leaf was removed and its area was determined using a leaf area meter (LI-3000, Li-Cor). It was

then dried to a constant mass at 60⬚C and weighed. Specific

leaf area was calculated by dividing the area of the leaf by

its mass.

In selection program 1, photosynthetic rate, stomatal

conductance, and transpiration rate were measured between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. on the day each

plant opened its first flower with the LI-6400, with irradiance set at 1500 mmol m⫺2 s⫺1 (saturating) and a leaf

temperature of 25⬚C. Flow rate was 500 mmol s⫺1, and the

S34 The American Naturalist

stomatal ratio was set at 0.4 (the ratio of stomata on the

two sides of the leaves in this species). All subsequent

measurements of physiology were taken 1 month after

flowering began for each plant for both selection programs.

To measure dark respiration of leaves in selection program

1, plants were watered to capacity and placed after dark

in a room without windows 2 nights before their 1-month

anniversary of flowering. Dark respiration was measured

with the LI-6400 with irradiance set to 0. A low-intensity

orange incandescent bulb, directed away from the plants,

was the only illumination used. Measurements were made

from approximately 6 to 7 a.m. The plants were then

moved into a greenhouse with overhead lighting and watered as needed in the morning and afternoon. The next

morning, the plants were again watered to capacity around

8 a.m. Between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration

rate were measured as listed above for plants from both

selection programs. Dark respiration of the leaves was

measured in selection program 2 directly after the above

measures, by lowering the irradiance to 0 and waiting for

the values to equilibrate. This method of measuring dark

respiration (whereby the whole plant was not in the dark)

is likely to lead to higher values in comparison to the

method used for selection program 1, and consequently

the absolute values cannot be compared across the selection programs. The latter method would be influenced by

recently accumulated substrate for respiration in the

leaves; however, unless there was an interaction between

this substrate and the selection lines, this would only affect

the absolute values and not the relative values across the

selection lines.

Stem respiration was also measured using the LI-6400

on a subset of plants not used for leaf measurements in

selection program 1. Stems from 10 males and nine females

were measured (79 stems from males, 65 stems from females; sex did not have a significant effect on stem respiration, P p .62). We chose stems in order to get the full

range of stem diameters and used multiple stems per plant.

Large stems are necessarily older than small stems because

stem diameter decreases incrementally with each branching event. Plants were treated as above for measuring dark

respiration of the leaves in selection program 1. Stem respiration was measured by cutting stems from the plants

and immediately placing the stem within the cuvette, parallel to the cuvette’s long side (such that the cut ends were

outside the cuvette). This excluded respiration from

wounding. After this measurement, the diameter of each

stem was measured with digital calipers. The stems are

round, so stem area (which must be entered into the LI6400 for calculations of respiration based on area) was

calculated as 2prh (the surface area of the side of a cyl-

inder), where r p diameter/2 and h equaled the length of

the cuvette.

Biomass allocation was determined for each plant 1

month after flowering. The plants were pulled apart into

the following components: reproductive parts, leaves, and

stems. The stems were subsequently divided into four categories based on diameter. Here we report on the biomass

invested in leaves and the smallest stem diameter category,

!0.8 mm. All leaves and stems were dried to a constant

dry mass at 60⬚C and weighed to obtain vegetative dry

mass for each plant.

Statistical Analyses

To determine whether each of the traits listed in table 1

showed a correlated response to selection on calyx width,

we performed one-way ANOVAs with sex and selection

line combined into one categorical variable (1 p smallline males, 2 p control males, 3 p large-line males, 4 p

small-line females, 5 p control females, 6 p large-line

females). Separate analyses were run for the two selection

programs. If the ANOVA for a particular trait was significant, a series of planned nonorthogonal pairwise comparisons was used to determine which sex/line combinations differed significantly from each other. A significant

difference among selection lines within a sex was taken as

evidence for a significant correlated response. In addition,

the elimination of a significant difference between the sexes

(by comparing large-line males with small-line females)

or the creation of a significant difference between the sexes

(by comparing small-line males with large-line females)

was also tested. The replicate lines in selection program 2

were combined for analysis. Levene’s test for homogeneity

of variances was run, and t-tests assuming either equal or

unequal variances were employed, depending on the outcome of the test. We employed the sequential Dunn-Sidák

method to adjust our experimentwise error rate (Sokal

and Rohlf 1995, p. 241).

Results

Means of traits by sex and selection line, along with the

one-way ANOVA and significant pairwise comparison results, are all presented in table 1, unless otherwise indicated. Table A1 in the online edition of the American Naturalist contains the P values and degrees of freedom for

all nine pairwise planned nonorthogonal comparisons for

each trait.

Biomass Allocation

Total leaf biomass showed a significant correlated response

to selection in both selection programs. In selection pro-

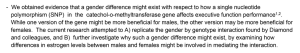

Table 1: Means (SE) of traits for the different selection lines in the last generation of both selection programs for males and females and results of the one-way ANOVAs

Males

Trait

Selection program 1:

Total leaf biomass (g)

Small stem biomassb (g)

Vegetative biomassb (g)

Specific leaf area (cm2 g⫺1)

Photosynthesis (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Photosynthesisb (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Stomatal conductance (mol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Stomatal conductance (mol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Transpiration (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Transpiration (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Dark respiration (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Selection program 2:

Total leaf biomass (g)

Small stem biomass (g)

Vegetative biomass (g)

Specific leaf area (cm2 g⫺1)

Photosynthesis (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Stomatal conductance (mol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Transpiration (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

Dark respiration (mmol m⫺2 s⫺1)

a

Time

F (df)

(5, 199)

(5, 135)

(5, 136)

(5, 174)

(5, 308)

(5, 168)

(5, 308)

(5, 222)

(5, 308)

(5, 222)

(5, 154)

P

MF

MF

MF

MF

F

MF

F

MF

F

MF

MF

5.81

23.29

4.92

8.10

.33

8.49

1.33

5.21

.55

5.70

5.30

MF

MF

7.02 (5, 270) !.001

41.03 (5, 272) !.001

MF

MF

MF

MF

MF

MF

9.82

8.98

3.73

2.67

4.63

11.34

(5, 268)

(5, 273)

(5, 249)

(5, 249)

(5, 249)

(5, 248)

!.001

!.001

!.001

!.001

.894

!.001

.252

!.001

.742

!.001

!.001

!.001

!.001

.003

.023

!.001

!.001

1. Small

2. Control

Females

3. Large

4. Small

5. Control

6. Large

2.3 (.11)

2.1 (.10)

2.9 (.19)

2.4 (.10)

2.6 (.11)

2.8 (.13)

.65 (.054)

.66 (.058)

.46 (.047)

.25 (.55)

.16 (.052)

.11 (.042)

6.4 (.33)

6.3 (.28)

7.5 (.42)

7.7 (.31)

8.0 (.39)

8.1 (.45)

308 (15.1)

314 (9.8)

254 (12.2)

328 (9.9)

295 (6.4)

272 (6.6)

19.2 (.47)

18.6 (.49)

19.3 (.50)

18.7 (.40)

18.7 (.39)

18.9 (.40)

8.5 (.40)

8.1 (.41)

7.8 (.55)

6.3 (.45)

6.2 (.46)

5.5 (.33)

.52 (.020)

.51 (.025)

.48 (.023)

.47 (.018)

.50 (.021)

.46 (.018)

.19 (.016)

.19 (.014)

.17 (.015)

.15 (.010)

.14 (.009)

.13 (.007)

5.1 (.13)

4.8 (.17)

4.9 (.19)

4.8 (.16)

4.9 (.14)

4.9 (.14)

2.8 (.17)

2.7 (.14)

2.5 (.18)

2.2 (.12)

2.1 (.10)

2.1 (.10)

⫺.81 (.086) ⫺.72 (.065) ⫺.52 (.085) ⫺.47 (.058) ⫺.50 (.055) ⫺.40 (.064)

1.9 (.07)

1.3 (.05)

2.4 (.09)

1.0 (.06)

2.3 (.08)

.8 (.04)

2.3 (.07)

1.2 (.04)

2.6 (.10)

.7 (.05)

Significant comparisonsb

1-3,

1-3,

1-6,

1-3,

1-6, 2-3, 2-5, 4-6

1-6, 2-3, 2-5, 3-4

2-5

2-3, 3-4, 4-5, 4-6

1-6, 2-5

1-6, 2-5

1-6, 2-5

1-3, 1-6

2.5 (.10)

.6 (.03)

1-2, 1-3, 1-6, 4-5

1-2, 1-3, 1-6, 2-3, 2-5, 3-4,

4-5, 4-6, 5-6

5.1 (.16)

5.6 (.25)

5.4 (.18)

6.5 (.17)

6.6 (.23)

6.2 (.23)

1-6, 2-5, 3-4

249 (5.9)

220 (6.9)

220 (4.2)

228 (5.2)

196 (6.4)

216 (4.7)

1-2, 1–3, 1-6, 4-5

10.2 (.33)

9.6 (.36)

9.8 (.36)

9.8 (.39)

9.3 (.50)

8.3 (.34)

1-6, 4-6

.16 (.007)

.15 (.010)

.16 (.010)

.14 (.007)

.13 (.008)

.13 (.008) 1-6

2.8 (.13)

2.6 (.21)

2.7 (.13)

2.3 (.09)

2.1 (.11)

2.2 (.10)

1-6

⫺1.26 (.042) ⫺1.03 (.041) ⫺1.00 (.046) ⫺1.07 (.048) ⫺.90 (.040) ⫺.86 (.040) 1-2, 1-3, 1-6, 4-6

Note: For selection program 2, the means for the two replicate small and two replicate large lines are shown combined. Nine planned nonorthogonal pairwise comparisons were made for each trait (see

“Statistical Analyses”). Only significant pairwise comparisons are listed here (designated by the numbers in the column headings); see table A1 for all comparisons. Control values in boldface indicate

significant sexual dimorphism for the trait (comparison 2 vs. 5). Small stems are those with a diameter of !0.8 mm.

a

F p measured on the day the first flower opened on a plant; MF p measured 1 month later.

b

Traits in selection program 1 for which pollinated and unpollinated females differed from one another. The means include only unpollinated females in these cases.

S36 The American Naturalist

Figure 1: Mean (⫹SE) number of flowers produced by pollinated (gray

bars) and unpollinated (black bars) females in the three selection lines

(Small p small-flower line, Control p control line, Large p largeflower line). Different superscripts indicate significant differences among

treatment groups (Tukey’s). See Delph et al. (2004a) for flower number

data for males.

gram 1, males and females in the large line invested 32%

and 17% more in leaf biomass, respectively, than those in

the small line, and these differences were statistically significant. In addition, the large line differed significantly

from the control line for males. Moreover, the significant

sexual dimorphism that existed between the control-line

males and females (control females invested 24% more in

leaves than control males) was reversed when comparing

males in the large line with females in the small line: largeline males invested 21% more than small-line females.

Finally, the sexual dimorphism was expanded when comparing individuals with the most extreme differences in

flower size and number, with females in the large line

investing 27% more in leaves than males in the small line.

Changes in total leaf biomass were similar in selection

program 2. Both males and females showed a significant

correlated response. Males in the small line invested significantly less than those in the control and large lines

(26% and 21%, respectively), and females in the small line

invested significantly less than those in the control line

(13%). Control-line males and females did not differ significantly, but a significant difference was seen when comparing the two extremes: females in the large lines invested

32% more than males in the small lines.

The amount of biomass invested in small stems (!0.8

mm) was affected by pollination, with pollinated females

making significantly fewer small stems than unpollinated

females (mean Ⳳ SE p 0.04 Ⳳ 0.019 g vs. 0.17 Ⳳ 0.029 g,

respectively; one-way ANOVA on log-transformed means

[⫺1.24 vs. ⫺0.73]: F p 9.77, df p 1, 53, P p .003). Because plants produce a new axillary branch, each of which

is smaller than the preceding branch, whenever they make

a new flower, this effect is likely a consequence of pollinated females producing significantly fewer flowers than

unpollinated females (one-way ANOVA on log f lower

number, with pollination treatment and selection line

combined into one categorical variable: F p 176.20,

df p 5, 116, P ! .001; Tukey’s a posteriori contrasts shown

in fig. 1). Note that in spite of the significantly lower overall

production of flowers in pollinated females, pollinated females in the small line produced more flowers than pollinated females in the large line (P ! .001). Hence, fruit

production did not eliminate flower number differences

between the selection lines.

The amount of biomass invested in small stems showed

a correlated response to selection in both selection programs. In selection program 1, males in the small and

control lines invested significantly more in small stems

than males in the large line (141%), and males from all

three lines invested significantly more in small stems than

females. Males in the control line invested 76% more than

did control-line females, and those that differed the most

in their flower production (males in the small line vs.

females in the large line) differed the most dramatically.

In selection program 2, all nine pairwise contrasts were

significant, indicating a correlated response in both males

and females, sexual dimorphism between the control-line

males and females, and both a reversal and an expansion

of sexual dimorphism when comparing large-line males

Figure 2: Relationship between carbon loss via respiration (mmol m⫺2

s⫺1) and stem diameter (mm).

Genetic Correlations and Sexual Dimorphism

with small-line females and small-line males with largeline females, respectively.

We report on the amount invested in small stems because carbon is lost through stem respiration, and the

amount of carbon lost depends on the diameter of the

stem (fig. 2). Stems with the smallest diameter (!0.8 mm)

have the highest surface-to-volume ratio and lose carbon

at a faster rate than older, thicker stems. Hence, plants

that make a relatively high number of flowers and a relatively high number of small stems will be losing more

carbon via stem respiration than plants with fewer small

stems.

The amount of biomass invested in vegetative structures

was affected by pollination. Unpollinated females invested

25% more in leaves and stems than pollinated females

(mean Ⳳ SE p 7.9 Ⳳ 0.23 vs. 6.3 Ⳳ 0.20; one-way

ANOVA: F p 24.98, df p 1, 120, P ! .001). Control-line

males and females exhibited significant sexual dimorphism

in vegetative biomass, with females investing more than

males. This dimorphism was eliminated by selection to

increase flower size in males and reduce flower size in

females in selection program 1 but not in selection program 2. However, the dimorphism was expanded in both

selection programs, with females in the large lines investing

21% and 18% more than males in the small lines in selection programs 1 and 2, respectively.

Leaf Physiology

Specific leaf area showed a correlated response to selection

in both selection programs: selecting for large flowers in

males led to a decrease in specific leaf area (thicker leaves),

and selecting for small flowers in females led to an increase

in specific leaf area (thinner leaves). Plants in the large

lines generally had thicker leaves than those in the small

lines. Lastly, although the sexes in the control lines were

not significantly dimorphic in either program, males in

the small lines had significantly thinner leaves than females

in the large lines.

Photosynthetic rate was measured on the day the first

flower opened in selection program 1. The one-way ANOVA

was not significant (F p 0.33, df p 5, 308, P p .894), indicating that photosynthesis at the time of first flowering

did not differ significantly by sex or selection line.

Photosynthetic rate 1 month after the onset of flowering

differed significantly between pollinated and unpollinated

females in the large line (one-way ANOVA: F p 5.79,

df p 1, 45, P p .020). The pollinated females in this line

photosynthesized at a higher rate than those that were not

pollinated (mean Ⳳ SE p 7.0 Ⳳ 0.54 vs. 5.5 Ⳳ 0.33 mmol

m⫺2 s⫺1).

The selection programs differed somewhat in terms of

how sex and selection line affected photosynthetic rate 1

S37

month after the onset of flowering, but overall, plants that

made more flowers had higher rates of photosynthesis than

those with relatively fewer flowers. In selection program

1, males and females in the control line differed significantly, with males photosynthesizing at a higher rate (23%

higher), but this sexual dimorphism was reduced to nonsignificance by selection to reduce the sexual dimorphism

in flower size. The dimorphism was also expanded, with

males in the small line photosynthesizing at a 35% higher

rate than females in the large line. In selection program

2, the mean photosynthetic rates of small-line males and

females are likely to be underestimates, because the leaves

of 18 plants in the small lines had already browned and

were no longer capable of photosynthesis 1 month after

flowering (this would also be true for stomatal conductance and transpiration rate; see below). This also occurred

in two control-line plants, but it did not occur in any of

the large-line plants. Nevertheless, in selection program 2,

females showed a correlated response to selection, with

females in the large lines photosynthesizing at a 15%

higher rate than females in the small lines. Finally, significant differences were seen between males in the small

lines and females in the large lines.

Just as with photosynthesis at the time of first flowering,

there were no significant differences between the sexes or

selection lines in stomatal conductance when flowering

first began (one-way ANOVA: F p 1.33, df p 5, 308,

P p .252). However, differences had developed 1 month

after the onset of flowering. In selection program 1, males

in the control line had a 26% higher conductance than

females in the control line, and this difference was significant. This dimorphism both became nonsignificant

(12% difference between males in the large line and females in the small line) and expanded (32% difference

between males in the small line and females in the large

line) by selection. Males and females in the control line

did not differ significantly in selection program 2, but the

difference between the sexes became significant after selection, with males in the small lines exhibiting a 19%

higher conductance than females in the large lines.

Similar to photosynthetic rate and conductance, transpiration rate did not differ significantly among the sexes

or selection lines at the time of first flowering (one-way

ANOVA: F p 0.55, df p 5, 308, P p .742). After 1 month

of flowering, males in the control line in selection program

1 were transpiring at a significantly higher rate than females in the control line (22% higher). Just as with conductance, this dimorphism both became nonsignificant

(12% difference) and expanded (25% difference). In selection program 2 the difference between males in the

small lines and females in the large lines was the only

significant difference.

Dark respiration of leaves showed a correlated response

S38 The American Naturalist

to selection in both selection programs. In selection program 1, males in the small line lost 36% more CO2 than

males in the large line, and this difference was significant.

Furthermore, a significant difference existed between

males in the small lines and females in the large lines, with

males respiring at a rate more than twice that of females.

In selection program 2, dark respiration was measured at

a different time of day than in selection program 1 (see

“Correlated Responses”), so the absolute values may not

be comparable between selection programs. Both males

and females showed a correlated response to selection in

selection program 2. Individuals in the small lines respired

more than 20% more than those in the large lines in both

sexes. In addition, small-line males respired significantly

more than control-line males. Finally, the sexes differed

significantly when comparing small-line males to largeline females.

Discussion

We created artificial-selection lines to determine whether

allocation and physiological traits were genetically correlated with flower size, a highly sexually dimorphic trait in

Silene latifolia. Specifically, we were interested in correlated

responses for traits that could account for males having

greater life-history trade-offs than females even though

they acquire more carbon and allocate less biomass to

reproduction. We hypothesized that sexual selection for

high flower production in males would also alter genetically correlated traits, with negative effects on their growth

and maintenance.

The correlated responses to selection we observed are

concordant with this hypothesis. Plants in the small-flower

lines produced more flowers than those in the large-flower

lines, indicating a flower size and number trade-off (data

reported in Delph et al. 2004a). Moreover, although pollination reduced flower production in females, it did not

eliminate the differences in flower production among the

selection lines. Because plants must produce a new branch

every time they make a new flower, higher flower production would carry any metabolic costs associated with

the differentiation of flowers, as well as maintenance and

nectar costs. A recent study has shown that whole-plant

nectar costs are greater for males than for females under

low-to-moderate levels of pollination as a result of their

greater flower production (Gehring et al. 2004).

In addition to a correlated response in flower number,

we found correlated responses in allocation and physiological traits. Individuals of both sexes with larger floral

displays produced less total vegetative biomass and less

leaf biomass, had thinner leaves, lost more carbon via stem

and leaf respiration, and had lower leaf life span than

individuals that produced relatively few flowers. The suite

of traits seen in the lines with the larger floral displays, as

compared to the suite seen in those with more limited

displays, indicates how males would be experiencing

greater losses of carbon as a result of continuous, high

flower production and therefore pay a higher cost of

reproduction.

Biomass Allocation

In terms of allocation, we found correlated responses in

total leaf biomass and small stem biomass in both selection

programs and for vegetative biomass in selection program

2. Selection to reduce flower size, which thereby increased

flower number, resulted in a decrease in the amount of

biomass a plant invested in leaves for both sexes. It also

resulted in an increase in the amount of biomass invested

in small stems, which were shown to experience relatively

high carbon loss through respiration. Similarly, significant

correlations between the percentage of total mass allocated

to leaves and stems with flower number were found in an

interpopulation study (Delph et al. 2002). These limits on

carbon gain and enhancement of carbon loss led to a

reduction in overall vegetative growth for individuals with

many, small flowers relative to individuals with few, large

flowers. Moreover, comparisons between males selected to

be more similar to females (large flowers) and females

selected to be more similar to males (small flowers) revealed that the sexual dimorphism that existed between

the sexes for two of these traits was eliminated by selection

in both selection programs: males no longer had less leaf

or vegetative biomass relative to females.

Leaf Physiology

Leaf physiological traits also responded to selection on

flower size, with the pattern being that plants with many,

small flowers showed an up-regulated physiology. For example, specific leaf area showed a correlated response to

selection in both selection programs. This trait is phenotypically integrated with other leaf functional traits in

the comparative physiology literature (Reich et al. 1992,

1998, 1999), but its heritability has not been widely studied

(Rebetzke et al. 2004). Specific leaf area appears to be

heritable and negatively genetically correlated with flower

size and hence positively correlated with flower number

in S. latifolia. In other words, plants of either sex that

make relatively many, small flowers have thinner leaves

than plants that make few, large flowers.

Thin leaves are typically associated with increased CO2

exchange and limited leaf life span in interspecific comparisons (Reich et al. 1999), and our results are consistent

with this pattern. Before flowering, neither the sexes nor

the selection lines differed in their photosynthetic rate,

Genetic Correlations and Sexual Dimorphism

stomatal conductance, or transpiration rate. However, 1

month after flowering began, differences emerged for these

traits, with the general pattern being that the values were

higher in the many-and-small-flowered line.

In selection program 1, the control line was sexually

dimorphic for all three of these traits, with males having

higher values than females. Selection to reduce the sexual

dimorphism in flower size resulted in elimination of the

sexual dimorphism in photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate. Furthermore, expansion

of the sexual dimorphism in flower size caused by a strong

between-sex genetic correlation for flower size (see Delph

et al. 2004a) expanded the differences between the sexes,

especially for photosynthetic rate.

In selection program 2, measures of gas exchange were

made difficult by an effect of selection line on leaf life

span, which is an interesting result in and of itself. Nearly

20% of the individuals in the small-flowered line had leaves

that had senesced before the 1-month timetable for

measuring their gas exchange, whereas all of the largeflowered-line plants still had functional, green leaves at this

time. This reduced leaf life span would cost the plant carbon;

most of the carbon and half the nutrients in senesced leaves

are lost to the plant (Chapin 1991), and these leaves would

no longer be fixing carbon. It is likely that the senesced

leaves had the highest CO2 exchange before their senescence,

given that leaf life span is highly negatively correlated with

photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance in a variety

of species (Ackerly and Reich 1999). Consequently, our

measures of gas exchange are likely underestimates for the

many-and-small-flowered plants. In spite of this, we observed correlated responses in photosynthetic rate in selection program 2, with photosynthetic rate being higher in

the small-and-many-flowered line, indicating that this trait

is heritable and genetically correlated with flower size in

that population. In addition, stomatal conductance and

transpiration were significantly different when comparing

individuals that differed the most in their flower size and

number, that is, males who made the most flowers and

females who made the fewest flowers.

Finally, we observed a correlated response in dark respiration of leaves in both selection programs, with individuals in the many-and-small-flowered lines exhibiting

relatively high rates of carbon loss compared to those in

the few-and-large-flowered lines. These results indicate

that dark respiration of leaves is heritable and negatively

genetically correlated with flower size. Although previous

research indicated sexual dimorphism in dark respiration

rates, with males having higher respiration (Laporte and

Delph 1996), the differences between the sexes in the control lines were not significant in either of our selection

programs, although the trend was for males to have higher

rates. However, this loss of carbon through respiration was

S39

significant when comparing the two most extreme groups,

with males in the small line losing more than twice as

much and 1.5 times as much carbon as females in the

large line in selection programs 1 and 2, respectively.

Trait Integration and Opposing Selection

The suite of leaf functional traits seen across the selection

lines mirrors patterns seen at the macroevolutionary scale,

in which species with thin leaves exhibit relatively fast

growth rate, higher carbon assimilation rates, higher respiration rates, and shortened leaf life span (Reich et al.

1998; Ackerly and Reich 1999; Ackerly et al. 2000; Arntz

and Delph 2001). Coordinated changes in physiology have

also been shown in response to environmental variation,

including environmental stress (Chapin et al. 1993; Ackerly

et al. 2000). Our results indicate that trait integration extends beyond ecophysiological traits.

Importantly, the correlated responses we saw to selection on flower size in S. latifolia indicate that neither traits

related to floral display (flower size and number) nor ecophysiological traits may respond independently to selection. This may be, in part, because physiology is upregulated in this species when sink strength (e.g., flower

number) is increased (Laporte and Delph 1996), and

flower number and physiological features co-varied in our

study. However, quantitative trait loci analysis of a cross

between the selection lines indicates that the correlated

responses of physiological traits was, at least in part, a

consequence of genetic polymorphism at loci controlling

these traits varying among the selection lines (L. F. Delph,

I. Scotti, and A. M. Arntz, unpublished data).

If there is strong sexual selection for elaborate floral

displays in males that is not countered by selection on

ecophysiology, then the genetic correlations between

flower size and ecophysiology seen here will result in selection for an up-regulated physiology. Conversely, there

could be strong selection to down-regulate physiology in

certain environments. For example, selection to limit water

loss in dry habitats might select for thicker leaves (Reich

et al. 1999) and lower rates of CO2 exchange (Farquhar

and Sharkey 1982). Such selection would indirectly cause

the evolution of fewer, larger flowers.

As a consequence of genetic correlations, if variation

existed among populations in the degree of sexual selection

on floral display or selection on ecophysiology, some populations might have relatively many and small flowers and

thin leaves with a shortened life span, whereas other populations might have relatively few and large flowers and

long-lived, thick leaves. This type of variation and covariation among traits is exactly what was found in a ninepopulation study (Delph et al. 2002). The two most extreme populations for these traits were from Croatia and

S40 The American Naturalist

Portugal, with the former resembling the many-and-smallflowered selection line and the latter resembling the fewand-large-flowered selection line. Further work, involving

multivariate-selection analysis combined with reciprocaltransplant experiments, is planned to determine which

traits contribute directly to fitness in different populations.

In summary, we tested the hypothesis that divergent

intersexual selection on one trait, flower number, would

cascade through the phenotype as a result of genetic correlations among traits and lead to a higher cost of reproduction for males. Evidence from our artificial-selection

experiments and interpopulation studies with S. latifolia

supports this premise. The next step will be to evaluate

the siring success of males in the divergent selection lines

and relate this to measures of their viability and longevity

in the field, as a direct test of whether traits that enhance

the one are opposed by the other.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many people who helped with the artificial

selection, including M. Banet, J. Bradlaw, R. Davis, G.

Harp, B. Helman, L. Kao, F. Knapczyk, B. Koskella, M.

Rummel, E. Rumschlag, G. Sellhorn, E. Vozar, and S. Wenzel. This work was supported by grants from Indiana University (IU) and the National Science Foundation (DEB9629774 to L.F.D. and J.L.G. and DEB-0075318 to L.F.D.)

and a grant to IU from the Howard Hughes Medical

Institute.

Literature Cited

Ackerly, D. D., and P. B. Reich. 1999. Convergence and correlations

among leaf size and function in seed plants: a comparative test

using independent contrasts. American Journal of Botany 86:1272–

1281.

Ackerly, D. D., S. A. Dudley, S. A. Sultan, J. Schmitt, J. S. Coleman,

C. R. Linder, D. R. Sandquist, et al. 2000. The evolution of plant

ecophysiological traits: recent advances and future directions.

BioScience 50:979–995.

Arnold, S. J. 1985. Quantitative genetic models of sexual selection.

Experientia 41:1296–1309.

———. 1992. Constraints on phenotypic evolution. American Naturalist 140(suppl.):S85–S107.

———. 1994. Multivariate inheritance and evolution: a review of

concepts. Pages 17–48 in C. R. B. Boake, ed. Quantitative genetic

studies of behavioral evolution. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

Arntz, A. M., and L. F. Delph. 2001. Pattern and process: evidence

for the evolution of photosynthetic traits in natural populations.

Oecologia (Berlin) 127:455–467.

Baker, H. G. 1948. Stages in invasion and replacement demonstrated

by species of Melandrium. Journal of Ecology 76:91–104.

Bell, G. 1980. The costs of reproduction and their consequences.

American Naturalist 116:45–76.

Carroll, S. B., and L. F. Delph. 1996. The effects of gender and plant

architecture on allocation to flowers in dioecious Silene latifolia

(Caryophyllaceae). International Journal of Plant Sciences 157:

493–500.

Carroll, S. B., and D. L. Mulcahy. 1993. Progeny sex ratios in dioecious Silene latifolia (Caryophyllaceae). American Journal of

Botany 80:551–556.

Chapin, F. S., III. 1991. Integrated responses of plants to stress.

BioScience 41:29–36.

Chapin, F. S., III, K. Autumn, and F. Pugnaire. 1993. Evolution of

suites of traits in response to environmental stress. American Naturalist 142(suppl.):S78–S92.

Conner, J. K. 2003. Artificial selection: a powerful tool for ecologists.

Ecology 84:1650–1660.

Darwin, C. 1871. The descent of man, and selection in relation to

sex. J. Murray, London.

Delph, L. F. 1999. Sexual dimorphism in life history. Pages 149–173

in M. A. Geber, T. E. Dawson, and L. F. Delph, eds. Gender and

sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Springer, Berlin.

Delph, L. F., and T. R. Meagher. 1995. Sexual dimorphism masks life

history trade-offs in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Ecology

76:775–785.

Delph, L. F., F. N. Knapczyk, and D. R. Taylor. 2002. Amongpopulation variation and correlations in sexually dimorphic traits

of Silene latifolia. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 15:1011–1020.

Delph, L. F., J. L. Gehring, F. M. Frey, A. M. Arntz, and M. Levri.

2004a. Genetic constraints on floral evolution in a sexually dimorphic plant revealed by artificial selection. Evolution 58:1936–

1946.

Delph, L. F., F. M. Frey, J. C. Steven, and J. L. Gehring. 2004b.

Investigating the independent evolution of the size of floral organs

via G-matrix estimation and artificial selection. Evolution and Development 6:438–448.

Farquhar, G. D., and T. D. Sharkey. 1982. Stomatal conductance and

photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 33:317–345.

Gadgil, M., and W. H. Bossert. 1970. Life historical consequences of

natural selection. American Naturalist 104:1–24.

Gehring, J. L., and Y. B. Linhart. 1993. Sexual dimorphisms and

response to low resources in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia

(Caryophyllaceae). International Journal of Plant Sciences 154:

152–162.

Gehring, J. L., and R. K. Monson. 1994. Sexual differences in gas

exchange and response to environmental stress in dioecious Silene

latifolia (Caryophyllaceae). American Journal of Botany 81:166–

174.

Gehring, J. L., J. Scoby, M. Parsons, and L. F. Delph. 2004. Wholeplant investment in nectar is greater for males than pollinated

females in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Evolutionary Ecology

Research 6:1237–1252.

Gross, K. L., and J. D. Soule. 1981. Differences in biomass allocation

to reproductive and vegetative structures of male and female plants

of a dioecious, perennial herb, Silene latifolia (Miller) Krause.

American Journal of Botany 68:801–807.

Lande, R. 1979. Quantitative genetic analysis of multivariate evolution, applied to brain : body size allometry. Evolution 33:402–

416.

Laporte, M. M., and L. F. Delph. 1996. Sex-specific physiology and

source-sink relations in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Oecologia (Berlin) 106:63–72.

Laurie, W. A., and D. Brown. 1990a. Population biology of marine

iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). II. Changes in annual survival

Genetic Correlations and Sexual Dimorphism

rates and the effects of size, sex, age and fecundity in a population

crash. Journal of Animal Ecology 59:529–544.

———. 1990b. Population biology of marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). III. Factors affecting survival. Journal of Animal

Ecology 59:545–568.

Lawrence, C. W. 1963. Genetic studies on wild populations of Melandrium. II. Flowering time and plant weight. Heredity 18:149–

163.

Lloyd, D. G., and C. J. Webb. 1977. Secondary sex characters in

plants. Botanical Review 43:177–216.

Lovett Doust, J., G. O’Brien, and L. Lovett Doust. 1987. Effect of

density on secondary sex characteristics and sex ratio in Silene alba

(Caryophyllaceae). American Journal of Botany 74:40–46.

Meagher, T. R. 1992. The quantitative genetics of sexual dimorphism

in Silene latifolia (Caryophyllaceae). I. Genetic variation. Evolution

46:445–457.

———. 1999. The quantitative genetics of sexual dimorphism. Pages

275–294 in M. A. Geber, T. E. Dawson, and L. F. Delph, eds. Gender

and sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Springer, Berlin.

Obeso, J. R. 2002. The costs of reproduction in plants. New Phytologist 155:321–348.

Rebetzke, G. J., T. L. Botwright, C. S. Moore, R. A. Richards, and A.

G. Condon. 2004. Genotypic variation in specific leaf area for

genetic improvement of early vigour in wheat. Field Crops Research 88:179–189.

Reich, P. B., M. B. Walters, and D. S. Ellsworth. 1992. Leaf life-span

in relation to leaf, plant, and stand characteristics among diverse

ecosystems. Ecological Monographs 62:365–392.

Reich, P. B., M. B. Walters, D. S. Ellsworth, J. M. Vose, J. C. Volin,

C. Gresham, and W. D. Bowman. 1998. Relationships of leaf dark

respiration to leaf nitrogen, specific leaf area and leaf life-span: a

test across biomes and functional groups. Oecologia (Berlin) 114:

471–482.

S41

Reich, P. B., D. S. Ellsworth, M. B. Walters, J. M. Vose, C. Gresham,

J. C. Volin, and W. D. Bowman. 1999. Generality of leaf trait

relationships: a test across six biomes. Ecology 80:1955–1969.

Schluter, D. 1988. Estimating the form of natural selection on a

quantitative trait. Evolution 42:849–861.

———. 1996. Evolution along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution 50:1766–1774.

Shykoff, J. A., and E. Bucheli. 1995. Pollinator visitation patterns,

floral rewards and the probability of transmission of Microbotryum

violaceum, a venereal disease of plants. Journal of Ecology 83:189–

198.

Sokal, R. R., and F. J. Rohlf. 1995. Biometry: the principles and

practice of statistics in biological research. W. H. Freeman, New

York.

Taylor, D. R. 1994. The genetic basis of sex ratio in Silene alba (pS.

latifolia). Genetics 136:641–651.

Trivers, R. L. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. Pages

136–179 in B. G. Campbell, ed. Sexual selection and the descent

of man 1871–1971. Aldine, Chicago.

van Nigtevecht, G. 1966. Genetic studies in dioecious Melandrium.

I. Sex-linked and sex-influenced inheritance in Melandrium album

and Melandrium dioicum. Genetica 37:281–306.

Wikelski, M., and F. Trillmich. 1997. Body size and sexual size dimorphism in marine iguanas fluctuate as a result of opposing

natural and sexual selection: an island comparison. Evolution 51:

922–936.

Wikelski, M., C. Carbone, and F. Trillmich. 1996. Lekking in marine

iguanas: female grouping and male reproductive strategies. Animal

Behaviour 52:581–596.

Young, H. J. 2002. Diurnal and nocturnal pollination of Silene latifolia

(Caryophyllaceae). American Journal of Botany 89:433–440.

Editor: Jonathan B. Losos