Rethinking the Impact of Surveillance

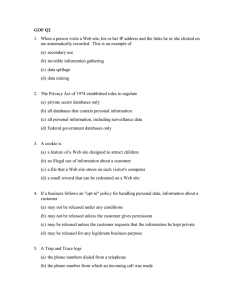

advertisement