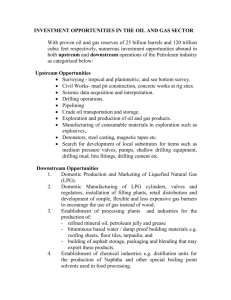

Accelerating the LPG Transition

advertisement