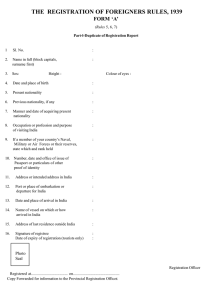

Nationality Unknown?

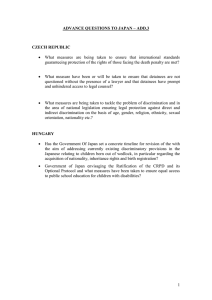

advertisement