here - National Heritage Board

advertisement

1

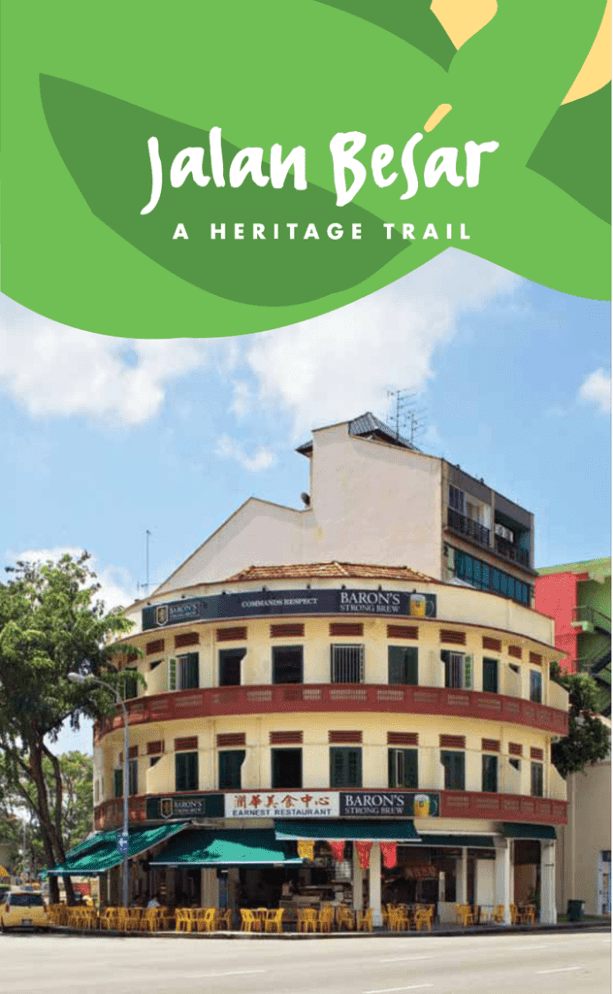

FROM SWAMP TO CITY:

THE STORY OF JALAN BESAR

The Jalan Besar Heritage Trail is a tale of two former swamps. First, we trace

the urban development of a floodplain that once existed on the north bank

of the Rochor River. Next, we chart the stories of the communities and

cultures that sprung up around the muddy basin of Singapore’s longest

waterway, the Kallang River.

The remnant swampland around Jalan Besar and the tidal flats of the

Kallang Basin have long been reclaimed. Shophouses, temples and churches

now occupy land once overgrown by mangrove trees and nipah palms.

Farmland has given way to schools, hospitals and a stadium. And once

bustling villages sustained by coastal trade have vanished as industries,

housing developments and parkland emerged to add a new dimension to

life on the eastern reaches of the Lion City.

Gone too, but certainly not forgotten, are New World and its gaudy host

of performers who sang, danced and performed for citizens in an era when

live entertainment was the only form of recreation in town. In between sets,

the audience probably sipped soft drinks brewed and bottled by beverage

factories located in the neighbourhood, which are, similarly, a mere memory

today. Little missed, however, are the less pleasant elements of the area:

the cattle and pig slaughterhouses, municipal refuse facilities, sawmills, oil

mills, rubber factories and brick kilns that once polluted the rivers and

almost certainly overpowered the senses of those who wandered too close.

The Jalan Besar Heritage Trail is part of the National Heritage Board’s ongoing

efforts to document and present the history and social memories of places in

Singapore that many may not be aware of. Jointly presented by the National

Heritage Board and Moulmein-Kallang Citizens' Consultative Committee, we

hope this trail will bring back fond memories for those who have worked, lived or

played in the area and serve as a useful source of information for new residents

and visitors.

NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY

MEANS, ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER.

FOR ALL COPYRIGHT MATTERS, PLEASE CONTACT THE NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD. EVERY EFFORT HAS BEEN MADE TO ENSURE THAT THE

INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS BROCHURE IS ACCURATE AT THE TIME OF PUBLICATION. NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD SHALL NOT BE

HELD LIABLE FOR ANY DAMAGES, LOSS, INJURY OR INCONVENIENCE ARISING IN CONNECTION WITH THE CONTENTS OF THIS BROCHURE.

PUBLISHED BY NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD IN AUGUST 2012.

www.nhb.gov.sg 1

SOURCE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

SOURCE: KIM KENG CHYE COLLECTION, COURTESY OF

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

In the early 20th century, tall silk-cotton trees lined parts of Jalan Besar. Nearby, by the banks of the Rochor River, were

villages built by Boyanese settlers, who lived in houses on tall stilts.

THE ‘BIG ROAD’ BECKONS

Today, thankfully, there is no risk of encountering

the foul establishments of a vastly different era.

But a stroll through the Jalan Besar neighbourhood all the way to the Kallang River will still

bring you past many traces – in buildings, streets

and other landmarks – of the pioneers who cut

the roads, cultivated the land and later, built

homes, hotels and factories.

Some buildings, such as the area’s conserved

shophouses and townhouses, have been subject

to few alterations in external form since the day

they were built, although their functions may

have changed. Others, such as the Jalan Besar

Stadium and former Victoria School, have undergone rounds of physical refurbishment and social

evolution to serve the needs of a different time.

Even empty plots and fields have tales to tell, of

merchants who lived in now-demolished mansions as well as massive industrial installations

such as the Kallang Gasworks that once supplied

light and energy to homes and factories.

To a newcomer, Jalan Besar and its surroundings may appear chaotic, with little sense of

architectural unity or ethnic identity. But the present neighbourhood is, in fact, the result of successive waves of settlements that gave rise to

diverse communities over more than 150 years.

First to arrive were the riverine tribes or Orang

Biduanda Kallang who lent their name to the

Kallang River. Then came Bugis traders from

Sulawesi and Boyanese seafarers who dwelled in

attap houses by the riverbanks.

02

Immigrants from China and the Indian subcontinent then landed to work in estates owned by

colonial pioneers and Arab businessmen. Rickshaw coolies, vegetable farmers and employees

of the former Kallang Gasworks eked a living for

themselves in the drained swamps. These same

labourers built temples, churches and clan associations that offered social and spiritual support

in a time when life could be nasty, brutal and

short.

A little later, shipbuilders, carpenters, mechanics and godowns set up shop by roads named

after the heroes of the First World War. An industrial air still lingers in some streets dominated by

hardware suppliers and derelict Art Deco warehouses, but this is tempered by a wealth of traditional coffee shops and eateries whose stalls

draw foodies from all over the island.

Jalan Besar’s grand old days may be long over.

But the neighbourhood and its landmarks offer

a rare glimpse into life “on the edge of the old

urban core” and a remarkable diversity of cultures and communities that had carved a space

for themselves on the former wetlands. As architect and historian Woo Pui Leng put it, “It was

arterial streets like Jalan Besar that helped transform Singapore from a rural possession into a

bustling colonial city.” The ‘Big Road’, as the

street was called early in life, may no longer

deserve the name, but Jalan Besar still looms

large in the history of Singapore and the people

who live, work and play in this quiet yet quaint

corner of the city.

SOURCE: ARSHAK C GALSTAUN COLLECTION, COURTESY OF

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

SOURCE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

Abattoirs, sawmills and other industrial buildings once occupied the Jalan Besar neighbourhood. Over time, these

industrial establishments gave way to shophouses, hotels and other commercial buildings.

“Jalan Besar was where I lived between 1921 and

1924. At that time the area between Syed Alwi Road

and Lavender Street was undeveloped. The ground

where the Beatty School and HDB houses are was a

big expanse of open ground. The place was full of

snipes [a long-billed wading bird] and a favourite

haunt of hunters. The other side of Jalan Besar

between Lavender Street and Syed Alwi was swamp

land. Flying ducks, snipe, fish, mud lobsters and

many-coloured snakes thrived there.”

– s. ramachandra, from singapore landmarks,

12 radio talks (1969).

THE ORIGINS OF JALAN BESAR

Most people are familiar with the founding of

modern Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles and

William Farquhar in 1819. In this tale of geopolitical intrigue and shared foresight, the two men led

a fleet of ships to the mouth of the Singapore River, where they bartered for trading rights in this

strategic natural harbour. For this privilege, Tengku Long (1776-1835) was installed as Sultan Hussein Mohammed Shah of Singapore, while

Temenggong Abdul Rahman (d. 1825), the real

power behind the throne, sowed the ground for

what would eventually become a new royal

dynasty seated in Johor.

Back then, the lower reaches of the Rochor and

Kallang Rivers, beyond the swamps that would

eventually give rise to Jalan Besar, were already

inhabited by native fisher folk who owed allegiance to the Temenggong. This is the story of

what took place since then, both in space and

time. This is a story of how a road grew, in length

as well as in richness, until it connected the city

to its eastern outskirts and witnessed the taming

of two rivers whose banks now brim with parkways and public housing.

FROM FRUIT TREES TO

INDUSTRIAL PLANTS

As late as the 1840s, the area between Serangoon Road and the Rochor River was dominated

in part by a swampland of low fields, mangroves

and waterways. The place must have resembled

Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Pasir Ris Park,

where some of the island’s surviving mangrove

habitats can be seen today.

Some of the Europeans who settled in Singapore in the first half of the 19th century took to

agriculture in the belief that the hot, humid climate would promote the growth of cash crops.

Joseph Balestier, the first American consul to Singapore, ran a sugar cane estate by the road that

now bears his name. Other entrepreneurs planted nutmeg in the suburbs off Orchard Road. Both

ventures were destined to fail, however, the first

due to tariff barriers and the second to disease.

A rather more successful attempt at agriculture arose when two brothers, Richard Owen

Norris (d. 1905) and George Norris, bought three

hectares of land from the East India Company in

the 1830s. Located north of the Rochor River and

costing 113 rupees, the land was turned into an

estate for betel nut, nipah palm and fruit trees

such as mangosteen. A road was carved through

03

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES © SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LIMITED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

road that has grown with the city and still gives

off a sense of nostalgia in its busy five-foot ways

and quiet little lanes.

Clockwise from top left: a soccer match at the Jalan Besar Stadium; the former Kallang Gasworks; kiddy rides at New

World; shanty houses in Kampong Bugis.

the estate, forming a raised bund over the

swampy ground.

Originally, the road led to nowhere, ending in a

sea of mangroves that reached Rochor Road to

the north. Beyond this marshy flank were some

of the earliest brick kilns in Singapore, which are

believed to have been set up by Naraina Pillai, a

trader of south Indian origin from Penang who

arrived with Raffles in 1819. In the 1830s, there

were also paddy fields and vegetable gardens run

by Chinese farmers, who fertilised their crops

using human waste. This foul-smelling practice

led to the cynical renaming of Rochor Road as

Lavender Street in 1858.

As the town expanded and traffic between its

centre and the peripheries grew in the 1880s, the

former dirt track was raised and extended until it

joined Lavender Street and was given the name

Jalan Besar, or ‘Big Road’. Even then, swampland

still covered much of the area south of Jalan

Besar and penetrated a good part north of it until

the 1930s. The transition from wetland to dry

plots was a lengthy process that involved the

dumping of municipal refuse over decades to

form solid ground on which new side streets

were laid out and shophouses were built.

Towards the end of the 19th century, sawmills,

oil mills and rice mills began to appear along Syed

Alwi Road by the Rochor River. Abattoirs also

04

sprang up amid this landscape of industrial edifices with tall, obelisk-like chimneys. The slaughterhouses were impressive buildings, with a tripartite (three-part) design featuring a church-like

central aisle, prominent side wings and high

clerestories (ventilation windows). Engineering

workshops, contractors and factories, along with

hotels, lodging houses, churches and temples,

emerged in the first half of the 20th century.

Complementing these scenes of industry and

devotion were leisure facilities in the form of New

World and the Jalan Besar Stadium.

The brick kilns vanished by the 1920s, as their

source of raw materials and fuel, the mangrove

swamps, dwindled to tiny pockets. It was during

this time, too, that many shophouses and other

landmarks were constructed on the former

swampland. Some, such as New World, Guan

Guan Hotel and the Framroz Aerated Water Factory, have not survived the changing tides of

taste and fortune that swept through the area in

the second half of the 20th century. But much of

the diverse histories of Jalan Besar, as seen in the

built heritage of the neighbourhood, remain evident to visitors, thanks to the granting of conservation status to selected buildings by the Urban

Redevelopment Authority since 1991. To date,

540 buildings in the area have been conserved,

preserving the character and charm of a big, bold

THE NORRIS BROTHERS

Richard Owen Norris and George Norris were the

sons of an East India Company army officer.

George Norris joined the government service and

became an Assistant Treasurer in Penang. Richard Owen Norris remained in Singapore where he

lived in a bungalow with his 10 children on the

family estate. Norris Road, which was built in

front of the brothers’ estate in the 1890s, was

named after the family at their request.

More than four generations later, the Norris

family is still active in Singapore. The Norris Block

at the Singapore General Hospital commemorates Dr. Victor Norris (d. 1942), grandson of

Richard, who was killed by bombs dropped on

Kandang Kerbau Hospital during the Second

World War. Dr. Norris’ daughter, Noel Evelyn

Norris (b. 1918), was principal of Raffles Girls’

School from 1961 to 1977.

THE NIPAH AND BETEL PALMS

Native to Southeast Asia, the nipah (Nypa

fruticans) is a species of palm that grows in

sheltered tidal swamps alongside mangroves.

Unlike other palm trees, the nipah's main trunk

runs horizontally under the mud and sends out

shoots that bear long leaves. Nipah leaves are

used to thatch the roofs of attap huts. The

immature seed is the source of attap-chee, a jellylike component of popular local desserts such as

ice kachang. Sap from the flowers is extracted to

produce toddy, a strong alcoholic beverage.

The seeds of the areca or betel palm (Areca

catechu) have been used for centuries throughout

South and East Asia as a spice and stimulant.

Thinly sliced and wrapped in daun sireh (betel

leaves, which are obtained from a vine known

scientifically as Piper betle) with a dash of lime

(chalk, not the fruit), betel is chewed to produce

a soothing, slightly narcotic sensation. Spices

such as cloves, cardamom, turmeric, dry coconut,

saffron and sugar are sometimes added for

flavour. The habit also causes the saliva and

gums to turn red. In India, paan, which combines

ground areca nuts and spices, is chewed as a

post-meal digestive. Betel palm fibres were once

made into beige sheets called opeh, which people

used as food wrappers in the days before

styrofoam and plastic containers.

KAMPONG KAPOR

Kampong Kapor was a village off Jalan Besar, formerly located around the present day Desker and

Veerasamy Roads, named after the lime or kapor

that accompanied betel consumption. The Tamil

name of the area was Sunnambu Kampam or

‘Lime Village’. Lime was also an important component of Madras Chunam, a durable building

plaster that originated from India and was manufactured in nearby kilns. Made from lime, egg

white, sand, shell and sugar, Madras Chunam

was used to create the glossy white exterior of

buildings such as St Andrew’s Cathedral.

A TREE-LINED AVENUE

An avenue of kapok trees (Ceiba pentandra) once

lined the northern outskirts of Jalan Besar. These

trees have tiny flowers but can reach a height of

60 metres with a trunk girth of 10 metres. They

are also called silk-cotton trees as the fruit consists of a water-resistant fibre that can be used

to stuff pillows, mattresses and life-jackets. The

trees were chopped down in the 1920s, but surviving examples of this majestic tree can be seen

in the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

THIEVES MARKET

Don’t miss the Sungei Road Market located in the

lanes between Weld Road and Sim Lim Tower at

the lower end of Jalan Besar. Popularly known as

the Thieves’ Market or Robinson Petang (‘Evening Robinson’ after a major department store),

this street bazaar began in the late 19th century

as a marketplace for mobile hawkers. The common nickname stems from the perception that

many of the goods on sale were acquired through

illegitimate means. The present market, though

a far cry from its heydays in size and splendour, is

still a place to go for steals such as vintage cameras, old photographs, books and trinkets.

›› did you know?

Paying little heed to official nomenclature, the Chinese who lived or worked in the area during the late 19th century

had their own names for Jalan Besar, calling it 'Kam-kong ka-poh thai-tu long' in Hokkien and 'Kam-pong ka-pok

thong-chu

fong'

Cantonese.

Boththrough

phrases meant

the same

thing: ‘The

depotTua

in Kampong

We suggest

youinbegin

your walk

the Balestier

Heritage

Trailslaughter-pig

at the Goh Chor

Pek KongKapor’,

Temple

referring

prominent

abattoirs between

DeskerRoads.

and Rowell Roads (the site of the present Rowell Court).

near the to

junction

of Moulmein

and Balestier

05

Syed Alwi Road

We begin the trail here, at a road that still ran by a remnant

swampland as recently as 1924. Built in the 1850s and originally

named Jalan Bahru, the street was later renamed Syed Alwi

(Alwee) Road.

There has been some uncertainty over the origins

of the road's name, as it is unclear whether it was

named after Syed Alwi (Alwee) bin Ali Aljunied

(1845-1926) or his father Syed Ali (Allie) bin

Mohammed Aljunied (1814-1858). But the son is

the likelier candidate as Syed Ali had a road

named after him in 1852 that was renamed Newton Road in 1914 to avoid confusion with Syed

Alwi Road.

The Aljunieds, who originated from Yemen

and are descendents of the Prophet Mohammed,

have been a prominent part of Singapore’s civic

and community life for more than 190 years.

Syed Sharif Omar Aljunied (1792-1852) and his

uncle Syed Mohammed bin Harun Aljunied (d.

1824) came to Singapore from Palembang,

06

Sumatra, soon after Raffles founded the trading

settlement in 1819. They soon established themselves as major traders and landowners who

shared their wealth with the community. The

family contributed to the building of the Masjid

Omar Kampong Melaka off Havelock Road (Singapore’s oldest mosque) as well as gave land for

St Andrew’s Cathedral and Tan Tock Seng’s Pauper’s Hospital.

Syed Ali, who bought 70 acres of swampy land

in Kampong Kapor and established a family

house in Balestier Road, was noted for his valued

construction of wells at Selegie Road, Kampong

Malacca, Telok Ayer and Kampong Pungulu

Kisang (near Mohamed Ali Lane) to provide

fresh water to the public. Syed Alwi, his son, was

a Justice of the Peace who filled in the swampland purchased by his father to form Weld Road.

He also paid for the construction of bridges

across Arab Street, Jalan Sultan and Bencoolen

Street. Aljunied Road was named in 1926 following calls by Dr H.S. Moonshi (1895-1965), a

Municipal Commissioner, for a major road to be

named after the Aljunieds to honour their contributions to Singapore. (Formed in 1856, the

Municipal Commission was a body of esteemed

residents who oversaw the running of municipal

services, including the naming of roads).

toirs’. For similar reasons, the Cantonese called

it Thong-chu-fong pin sai a-lui kai. Older residents

of the area would remember an abattoir located

at the site of Blk 811 French Road near the eastern end of Syed Alwi Road as well as another near

the site of the present Jalan Berseh Hawker Centre. One resident even recalled seeing sheep,

cows and pigs on the streets leading to the

slaughterhouses, which closed only in 1969 after

new facilities were completed in Jurong.

Other industries in the area included a pineapple factory and the Sin Siong Lim Sawmill, the latter of which was established in 1912 by Dr. Yin

›› did you know?

Suat Chuan, medical partner and brother-in-law

Syed Alwi was also the first known developer of

of Dr. Lim Boon Keng. The sawmill, which was

shophouses along Jalan Besar. He submitted plans for

active until the 1960s, was used as an internment

13 buildings at the corner of Weld Road in 1886. The

camp and screening centre during the Japanese

buildings no longer exist.

Occupation. Song Lin Building (1 Syed Alwi Road)

now stands on the site of the former sawmill.

SLAUGHTERHOUSES AND SAWMILLS

Teck Heng Long Industrial Building (11 Syed Alwi

In the early 20th century, Syed Alwi Road was Road) is a surviving three-storey commercial

known as Sai-ek a-lui koi thai tu-long pi in Hokkien, development built in 1950 in a utilitarian, modwhich meant ‘Syed Alwi street beside the abat- ernist style.

07

Jalan Berseh, which runs parallel to Syed Alwi

Road, was originally a private road. It was named

Lorong Lalat or ‘Lane of Flies’ in 1920 due to the

proximity of a municipal refuse depot and incinerator, which attracted vermin as well as the disgust of nearby residents. Today, refuse generated

by households and industries is collected daily

and incinerated; the resulting ash is sent to

Semakau Landfill, an island near Pulau Bukom.

›› did you know?

Beyond the sawmills and rubber godowns, the banks

of the Rochor River between Syed Alwi Road and Jalan

Besar were once occupied by a village of 'pondoks'

(communal houses on stilts) called Kampong Boyan.

The Boyanese or Baweanese originate from Bawean, a

small island between Borneo and Java. Many Boyanese

who migrated to Singapore in the 19 th century settled

at Kampong Boyan and worked as gardeners, gharry

drivers or horse-trainers.

surround the oval windows, while the side pilasters (projecting wall columns) are richly decorated with flowery capitals and colourful tiles. The

plasterwork is robust yet delicate and Malay

woodcarvings adorn the doorways on the ground

floor. Until 1977, these shophouses were the site

of the Song Lim Market, which housed stalls that

sold provisions, groceries and poultry.

In the past, Syed Alwi Road was a busy market

street with various businesses and eateries that

catered to people who worked in the area. Today,

there are still many popular eateries: Gar Lok Eating House at 217 Syed Alwi Road is well-known

for Hakka beef noodles and yong tau foo (stuffed

bean curd), while a coffeeshop at 27 Maude

Road dishes out char kway teow (stir-fried flat

noodles with cockles) and yong tau foo.

“Syed Alwi Road used to be like

Chinatown in the 1980s. There were

stalls on the roadside selling fish,

vegetables, meat plus sundry shops.”

UNIQUE SHOPHOUSES

Today, Syed Alwi Road is still a busy avenue of

shophouses built from the late 1800s to the

– Mr Chow Chee Wing, 63, a teacher at Christ

1960s in a range of architectural styles. Some

Church Secondary School (now the People’s

Association headquarters).

units from the late 1920s are almost completely

bedecked with colourful ceramic wall tiles (see

“At Verdun Road and Maude Road,

214 Syed Alwi Road), while others have arched

windows with ventilation screens featuring elabthere was a kway teow shop and also

orate Malay tracery patterns. There are also richkang-chia mee for rickshaw pullers.”

ly ornamented shophouses with window tracery

in green and pink (the favoured colours of the

– Mr Phang Tai Heng, a long-time resident of

Jalan Besar.

Peranakans), ornate festoons or garlands and pillars bearing neoclassical Corinthian capitals in

contrasting colours, unit 216-2 being just one SWEE CHOON DIM SUM

191 Jalan Besar

example.

Another notable sight is a unique row of nine A landmark of Jalan Besar for nearly 50 years,

shophouses (61-69 Syed Alwi Road) next to New this restaurant is well-known for its wide assortWorld Centre. Built in an elegant, fanciful style ment of fresh and hand-made bao (Chinese buns

called Rococo, they are distinguished by a pair of stuffed with various ingredients) as well as dim

enormous œil de bœuf (ox-eye) window openings sum. This Cantonese term refers to a light meal

between a flat arched window on each second consisting of a choice of sweet and savoury finstorey. Pale green bas-relief festoon mouldings ger foods served in a small basket or saucer.

08

From the junction of Syed Alwi Road and Jalan Besar, make a right turn and walk against the traffic flow past

Maude and Kitchener Roads, until you reach Plumer Road, which faces the next featured site, New World.

Jalan Besar, facing Plumer Road

SOURCE: K F WONG COLLECTION, COURTESY OF NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

10

After the turmoil and trauma of the First World War (1914-1918),

and emboldened by the wealth of a post-war economic boom,

the 1920s became known as the Jazz Age or Roaring Twenties.

Reflecting this mood, New World opened in August 1923 to launch

an era of entertainment and show business that many older

Singaporeans still recall with fondness.

New World occupied an area bounded by

Jalan Besar, Kitchener Road, Serangoon Road and

Petain Road. From the start, the park was a magnet for people from all walks of life, from labourers to European merchants and even Malayan

royalty, who flocked to sample its range of spectacles, songs and more sensuous attractions.

There were boxing and wrestling matches, variety shows, lucky draws and cabaret acts. Teochew and Hokkien troupes, along with Malay

bangsawan groups, performed operas to thronging audiences. For the young-at-heart, there

was a Ferris wheel, merry-go-rounds and film

screenings, while income could also be disposed

of at stalls hawking trinkets, fashion and food.

Two brothers, Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng

Hock, were the original owners of New World.

Despite their professed lack of experience in

show business, the park prospered (and drew

the competition of rivals Gay World and Great

World) in a time when there were few leisure

activities available after work. Shaw Organisation became involved in New World in the 1930s

when it acquired a share in the park, which had

three cinemas: the Pacific, State and Grand.

Perhaps the most popular attraction was the

cabaret hall, which could hold as many as 500

couples. Costing 50 cents to a dollar for entry

(then a hefty sum), guests could dance the waltz,

tango, rhumba or foxtrot to the sound of a live big

band. In the evening, young men and towkay alike

could pay for the chance to sashay with cheongsam-clad beauties, who were popularly known

as taxi-girls, as a coupon had to be purchased at

the door before one could dance with them.

Three dances cost a dollar, and the girls got a cut

of just 8 cents per dance.

During the Second World War, the park was

kept open by the Japanese who made it a gambling den. After the war, New World gained a

new lease in life as the masses, including allied

soldiers stationed in Singapore, returned in

droves. The cabaret, damaged by bombs, was

rebuilt and reopened in December 1947 to a

“As a student, we used to operate in two

teams to see sword-fighting shows like the

One-armed Swordsman at New World.

One team would rush to queue up to buy

front stall tickets, costing 50 cents

each, while the other team would rush to

order Mee Pok Dry at the corner coffee

shop. Those amongst us who were more

daring and friendly with the ushers would

sneak to the back stall rows once the show

started. There was also a shop making very

good Malay satay just outside the bus stop.”

– Mr Lim How Teck, who studied at Victoria School

from 1964-1969.

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES © SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS

LIMITED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

New World

›› did you know?

9le^XKXeafe^eXd\[X]k\iX]iX^iXekYcfjjfd was a New World dance hall famous in the

(0,'jXdfe^]Xejf]af^\k#XDXcXpjfZ`Xc

dance. Clad in their best, men young and old

would dance with hostesses in sarong kebaya

to live music, which evolved from ronggeng

and cha-cha in the 1950s to rock-and-roll in

the 1960s. Playwright A. Samad Said (b. 1935)

nXj`ejg`i\[Yp9le^XKXeafe^kfg\eCXekX`K%

Pinkie' (T. Pinkie’s Floor), a play about a cabaret

girl in post-war Malaya.

11

SOURCE: WONG KWAN COLLECTION, COURTESY OF NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE.

“After the war, my father made me go to

a Chinese school called Pei Min Xue Xiao,

which was inside New World. The opera

house and theatres were used as classrooms

in the morning. I was there for one-anda-half years. That's why I speak Mandarin

quite well!"

– Mr Kesavan Soon, 73, former national sprinter

who represented Singapore in the 1956 Olympics in

Melbourne.

“I grew up near Jalan Besar in the

1970s and remember there were coffee

shops near New World with bars in the

basements. I think you can still find one

or two such bars along Kitchener Road."

– Mr Ho Chee Hoong, 42, a former resident.

crowd of thousands. The park also added salacious elements such as performances by Rose

Chan (1925-1987), the ‘Queen of Striptease’.

Other celebrated acts were the stunt-wrestler

King Kong alias Emile Czaya (1909-1970),

strongman Ali Ahmad or Mat Tarzan (b. 1937)

and boxer Felix Boy alias S. Sinniah (b. 1936).

Sakura Teng (b. 1948), a songbird popular in the 1970s,

launched her career at New World, aged 17.

The ‘Worlds’ declined in the 1970s when television and, later, home video became popular.

The crowds vanished and New World was at one

time occupied by a furniture showroom and a

church. The longest surviving amusement park,

New World finally closed in 1987 when the land

was bought for development into a condominium.

All that remained was an iron arch flanked by two

pillars at the Jalan Besar entrance facing Plumer

Road. In December 2010, this gateway was relocated to City Green, an urban park at the junction

of Serangoon and Kitchener Roads.

ONG SAM LEONG AND HIS SONS

The father of the brothers who started New

World, Ong Sam Leong (1857-1918) was a Peranakan entrepreneur with interests in rubber,

timber and real estate, including properties along

Tyrwhitt, Petain and Verdun Roads. He also

owned Batam Brickworks and was the sole general contractor to the Christmas Island Phosphate Co., Ltd. Ong lived in a house at Bukit

Timah called Bukit Rose and was a President of

the Ban Chye Ho Club, said to be the oldest Chinese Club in Singapore. A hardworking man till

the end of his life, Ong was fond of motoring and

sea trips during his spare time. He was buried in

the largest tomb (spanning three basketball

courts) in Seh Ong Cemetery, which is today part

of Bukit Brown. Sam Leong Road off Jalan Besar,

“In Cantonese, it was known as

San Sai Kai ✣ĝ㾓. I vaguely

remember that we had a granduncle who worked as a gate-keeper

at New World. So occasionally

when he was on duty, he’d let us in

without buying an entrance ticket.

Like Great World, New World had

the usual attractions like cinemas,

ghost train, merry-go-rounds,

shooting galleries, bumper cars,

restaurants and food and clothing

stalls. The ghost train would be

moving in the dark, and then come

to a sudden stop and a ghoulish

demon would light up in front of

you, accompanied by evil laughter. I

recall that the ‘demons’ were really

quite amateurishly made. I could

clearly see the coconut and husk

used for its head. It wasn’t scary at

all but still the girls screamed.

– Mr Lam Chun See, 59, a business

consultant.

formerly Paya Road, was renamed after him in

1928.

Ong Boon Tat (1888-1941) served on the

Municipal Commission and was a Justice of

the Peace. He died following an accident at his

house at Pulau Damar Laut (now part of

Jurong Island). Boon Tat Street (formerly

Japan Street) was named after him in 1946.

Ong Peng Hock (d. 1968) continued to run

New World with his partner Runme Shaw

(1901-1985) after the war. In 1946, he moved

from a residence at Tyrwhitt Road (which was

converted into the Eastern Hotel and later the

Foochow Building) to a house at East Coast

Road named Christmas Island Villa. Both

brothers were buried in tombs beside their

father’s at Bukit Brown.

From the former gateway to New World, continue up Jalan Besar until you reach the junction of Jalan Besar

and Petain Road. Turn left into Petain Road to visit the next featured site.

13

10-42 Petain Road

Petain Road Terrace

Houses

Shophouses and their residential

counterpart, the terrace house,

have been a quintessential

part of the Singapore urban

landscape ever since their

basic design was laid down in

Raffles’ Town Plan of 1822. In

essence, these buildings, which

range from two to five storeys,

form a continuous row of units

separated by common party

walls and linked in front by a

sheltered verandah popularly

known as a five-foot way.

designed by J.M. Jackson, these were the first

three-storey buildings along the road. The shophouses have many then-contemporary features

such as partial flat roofs and street-facing terraces on the top floor. Staircases leading to the fivefoot way separated the public ‘shop’ and private

‘house’ portions.

Most of the shophouses along Jalan Besar

were built between 1900 and 1939 and span

architectural styles from traditional to late and

Art Deco. Units built in the 1920s were highly

ornamented and expressed an urban grandeur

that reflected the wealth gained during a Malayan rubber and tin boom. One unmatched example is a row of 18 two-storey terrace houses along

Petain Road. Built in 1930 for Mohamed bin Haji

Omar, the houses reflect a contemporary obsession with glazed ceramic tiles, which cover the

ground facades and even the upper storey columns in lavish numbers. The architect, E.V. Miller, was actually a Modernist in the Bauhaus

The ground floor of a shophouse usually served school which favours rounded lines and streamas a business premise, while the upper storeys lined functionality over ornamentation and symwere occupied by the owner or rented out to oth- metry. Were it not for the dictates of his brief, the

er tenants. At last count, there were 235 shop- buildings might have turned out very differently.

houses lining Jalan Besar proper, a tangible

The townhouses, which were in danger of

record of architectural tastes from the 1880s to demolition in 1979, were built in a style often

the 1960s. The very first shophouses in the area known as ‘Chinese Baroque’, which blended neowere simple affairs: two-storey back-to-back classical features such as Greco-Roman columns

structures with a narrow frontage and a rear with elaborate capitals bearing Chinese motifs.

court. Three of the earliest surviving examples These units also incorporated colours favoured

are at 61-65 Jalan Besar; these were built in 1888 by the Peranakans. Complimenting the floral

by a man named Ismail Sah, probably as dwelling ceramic tiles are colourful plaster reliefs of birds,

places, as windows and doors formerly aligned trees and blossoms over terracotta finishes.

the five-foot way. There is little decoration, apart Many of the tiles along the five-foot way were

from a terrace over each rear court.

lost over time and had to be replaced by similar

Some decades later, in 1925, a landowner pieces made in Vietnam during their restoration.

named Mohamad bin Haji Omar built a row of Much of the original terra cotta flooring has

five shophouses with visible concern for visual been preserved to retain the vintage look of the

impact. Located at 235-243 Jalan Besar and walkway.

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES © SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LIMITED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

14

After exploring Petain Road, return to Jalan Besar, cross the street, make a right turn and walk until you

reach the junction of Allenby Road and Jalan Besar.

15

ROADS WITH A WORLD WAR I THEME.

In October 1928, the streets on this side of Jalan Besar were given Great War-related names by the

Municipal Commission to honour leading commanders and battles of the First World War.

KITCHENER ROAD

» after Field Marshall

Horatio Herbert Kitchener.

BEATTY ROAD

» after Admiral David Beatty.

VERDUN ROAD

» after the Battle of Verdun in

northern France in 1916.

PETAIN ROAD

» after Marshall Philippe

Petain, French Commander

of the Battle of Verdun.

SOMME ROAD

» after the Battle of the

Somme in France in 1916.

MARNE ROAD

¾X]k\iXdXafiYXkkc\j`k\Yp

the Marne River in France.

FLANDERS SQUARE

» after Flanders, a region at

the borders of France and

9\c^`ldk_XknXjXdXafi

battlefield.

MONS ROAD

» after the Battle of Mons in

Belgium in 1914.

FALKLAND ROAD

» after the Battle of the

Falklands in December 1914.

STURDEE ROAD

» after Sir Frederick

Charles Doveton Sturdee,

Commander-in-Chief of the

South Atlantic and South

Pacific.

JUTLAND ROAD

» This road became part of

Beatty Road in 1957. The

name commemorates the

pivotal Battle of Jutland off

Denmark between British

and German battleships

in 1916.

›› did you know?

N_`c\dfjkle`kj`ek_`jifnn\i\

residences, one unit near the centre

formerly housed a Hockchew temple

called Tian Shu Tang. It was easy

to recognise as the windows and

doors were painted in red. Songbird

enthusiasts also used to gather at

a nearby corner to display their

singing pets in cages.

K_\G\kX`eIfX[Xi\XnXjfeZ\

known as 'Keen Chio Kar', or ‘the

foot of the banana tree’ in Hokkien.

Chinese vegetable farms were based

here before the shophouses were

built. Before the Second World

War, the neighbourhood was a

red-light district. Even today, parts

of Flanders Square and Marne Road

have an unsavoury reputation.

K_\Zfcflijf]Xj_fg_flj\ZXe^`m\

you a clue about who its owners

were. Those with pastel shades

and an unrestrained use of colours

were probably owned by Malay or

Peranakan families.

17

(290 Jalan Besar)

(298 Jalan Besar)

International Hotel Allenby House

This pair of buildings at the

junction of Allenby Road and Jalan

Besar present an unmissable

gateway to the Jalan Besar

Stadium, with curving profiles

that frame the approach to

Tyrwhitt Road.

FUTSING BUILDING

2 Allenby Road

Built in 1988, the Futsing Building belongs to the

Singapore Futsing Association, which represents

people of Hockchia descent. The Hockchias originate from Fuqing, a city in Fujian, China and

speak their own dialect. The Futsing Association

was founded in 1910 to serve the Hockchia community, who were mostly trishaw or rickshaw

pullers and later, employees or owners of bus

Allenby House was built in 1928 and designed by companies. Today, there are 20,000-30,000 SinWesterhout and Osman for an owner named gaporeans of Hockchia descent.

Poi Ching Primary School, which is now based

Chittiar. The building was originally planned as a

three-storey shophouse with a stately neoclassi- at Tampines, was established by the associacal façade. A fourth floor was later added and the tion in 1919 at Victoria Street. In 2000, the

façade modified into a Georgian design that Futsing Association organised an international

exudes a sense of graceful monumentality. Inside, beauty pageant for Hockchia girls, which was

there is a central court surrounded on the upper said to be the first such event held by a clan body

floor by an open corridor lined with eight cubicles. in Singapore. The winner, a local beauty queen,

Within the court was a core of toilets, bathrooms was chosen from 31 contestants and bagged a

and kitchens. Allenby House was the first four- bungalow in Fuqing. Hockchia delicacies include

storey building along Jalan Besar as well as the deep fried oyster cakes and guang bing, a dry biscuit with a hole in the centre for stringing. This

first dedicated lodging house by the road.

Across the road lies the former International made it easy for soldiers to carry the biscuits

Hotel, which was built in 1937 for owner Chia Nai around their necks.

Cheong by the architectural firm of Ho Kwong

Yew. The hotel represented a second wave of

“Back in our kampong days, the

lodging houses and residential hotels that

traditional (Chinese) wedding banquet

emerged along Jalan Besar to cater to travellers

and businessmen. Inside, there were six cubicles

was made up of two separate sessions: one

and a service core laid out around a rear court.

in the afternoon for women folk, and the

The curved exterior features continuous projectother at night for the men. Later on, as

ing balconies made from reinforced concrete,

we moved into the seventies, this practice

which buffer the rooms from the environment.

The building now houses a coffee shop called Earwas gradually replaced by a single

nest Restaurant, which is well-known for stalls

wedding dinner, usually held at popular

selling prawn noodles and yong tau foo.

restaurants. I remember three such

Other notable hotels that used to operate

restaurants in particular. One was the

along Jalan Besar include the Kam Leng Hotel

Lai Wah Restaurant located at the top

(which opened in 1927 and was restored in 2012),

the five-storey Art Deco White House Hotel at

floor of a building along Jalan Besar,

1-3 and 5 Jalan Besar, and the Ngung Hin Hotel at

near to the junction with Lavender

the corner of Jalan Besar and Syed Alwi Road

Street, opposite the present Eminent

(now the site of New World Centre). Two shopPlaza. I think the building is still there

houses at 345 and 351 Jalan Besar, built in 1948

as part of a 1930 town plan for the district, were

today. Lai Wah was well known for its

also originally lodging houses. Though designed

Cantonese cuisine and its celebrity chef

by different architects, both units are similar, with

by the name of Tham Yui Kai.”

a central service core linked several cubicles. The

facades are articulated at the corners and mirror

– Lam Chun See, 59, on Lai Wah Restaurant (now

each other in a way, providing a balanced pasat Bendemeer Road), which opened in 1963 at

Kam Leng Hotel, 383 Jalan Besar.

sage into Sturdee Road.

18

19

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

CLAN ASSOCIATIONS

FRAMROZ AERATED

AROUND JALAN BESAR

WATER COMPANY

Clan associations arose in early Singapore as Framroz is a brand familiar to Singaporeans who

migrants formed self-help and mutual support grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. It was also the

groups based on their places of origin, surname name of a soft drinks company with a three-stoor dialect. A number of clan associations have rey factory at the site of the present Futsing

their headquarters in the Jalan Besar area. Some, Association. The firm was started in 1904 by Philike the Futsing Association and Foochow Asso- rozshaw Manekji Framroz (1877-1960), a Parsi

ciation (21 Tyrwhitt Road), have their own multi- born in Bombay, India, who arrived in Singapore

storey buildings, while others conduct their activ- in 1903. The business, which moved from Cecil

ities from shophouses. The Singapore Kiangsi Street to Allenby Road in 1952, was one of the

Association at 277 Jalan Besar, for instance, has first local manufacturers to make carbonated

its origins in 1935 when locals of Kiangsi (Jiangxi) beverages using fruit imported from California.

origin, numbering about 300, established a group By the late 1960s, the company was producing

to provide social and recreational amenities. more than 25 varieties of soft drinks, cordials and

Today, the association is part of the Sam Kiang squashes. The company was acquired by Ben

Huay Kwan, which embraces clan bodies from Foods, a local food company, in 1972, and wound

the provinces of Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. up a couple of years later.

The religion of the Parsis, or Zoroastrianism, is

Another prominent clan association headquarters is the four-storey Lee Clan General Associa- one of the ten religions represented in Singation building at 363A Jalan Besar. The Nanyang pore’s Inter-Religious Organisation and enjoys

Sim Clan Association is another clan association, the same status as other faiths. Zoroastrianism

based at the Wu De Building at 6A Beatty Road. was founded in Persia by the Prophet Zoroaster

3,000 years before the common era. Believers

who moved in India were called Parsis as they

originated from the Parsa province in Persia. The

first Parsi in Singapore was a man named

Muncherjee, who arrived in the 1820s. More Parsis came in the mid 19th century and established

themselves as merchants and professionals. Mr

Framroz was the first president of the Parsi Association of Singapore in 1954.

FORMER ENG WAH BUILDING

A stately Art Deco mansion built in 1932 once

stood opposite the Futsing Association at 3

Allenby Road. Reportedly a dwelling for Ong

Boon Tat, co-owner of New World, the building

was the headquarters of a Japanese battalion

during the war. Later, it was used to house the

movie archives of the Eng Wah Organisation. The

three-storey building was demolished in 2006 as

a fire had made it unsuitable for conservation.

“During our time, soft drinks were

not something most folks could afford

to consume everyday. Chinese New Year

was one of the few occasions when we had

practically free flow of soft drinks to the

delight of the kids. My favourites were

Sarsi and Ice Cream Soda. The famous

brand then was Framroz, and hence there

was no Pepsi for Chinese New Year.”

– Lam Chun See, 59, a business consultant.

At the end of Allenby Road, turn left and you will find yourself at Tyrwhitt Road, home of the Jalan Besar Stadium.

20

21

100 Tyrwhitt Road

For many decades, this was the scene of pulsating soccer matches

as well as stirring parades and festivals. Considered the birthplace

of Singapore football, Jalan Besar Stadium opened in December

1929 as a replacement for an older playing field at Anson Road. The

very first game before a crowd of 7,000 took place on Boxing Day

1929, between the Malayan Chinese and Malayan Asiatics teams,

with the former winning 3-2.

From 1932 to 1966, these grounds hosted

Malaya Cup matches, and later, the Malaysia

Cup tournament from 1967 until 1973, when the

National Stadium was built at Kallang. Apart

from soccer, hockey and rugby were also played

here. The stadium also serves as the headquarters of the Football Association of Singapore.

The original stadium was built on the site of

a swamp filled with municipal refuse from the

Jalan Besar incinerator and turfed with Serangoon grass, a local species of grass. The original

22

playing field, measuring 110 x 73 metres and surrounded by a cinder running track, had to be

raised by nine inches over a bed of ashes, earth

and sand to keep it from flooding during heavy

rains. There were three levels of concrete terraces for spectators with a seating capacity of 2,500

and standing space for 7,500 more.

During the Japanese Occupation, the stadium

was a major Sook Ching screening site. It was also

used as a language centre to teach the Japanese

language to civilians. After the war, the stadium

SOURCE: DAVID NG COLLECTION, COURTESY OF NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES © SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LIMITED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

Jalan Besar Stadium

regained its status as a hub for community and

national events; it was the venue for the first Singapore Youth Festival in 1955; the first Singapore

Armed Forces Day on 1 July 1969 and the National Day Parade in 1984.

The stadium was closed in December 1999 for

a major rebuilding programme. The original playing pitch was retained and the new facility reopened as part of the Jalan Besar Sports and Recreation Centre in June 2003 with a seating

capacity of 6,000. An adjacent hawker centre

and carpark made way for a public swimming

complex, and the most striking new feature is a

slightly arched steel roof resembling a suspension bridge over the southwest grandstand. In

2008, a further upgrade converted the pitch into

artificial turf to meet international guidelines.

“The stadium was the best in

British Malaya before Merdeka

Stadium was built in Kuala

Lumpur. In the 1960s, as a

kid, I watched my dream team

England play 'live' before my

eyes at Jalan Besar Stadium and

how they effortlessly trounced

Singapore 9-0; I had never

before seen Uncle Choo [Seng

Quee] so quiet throughout a

match. There were also dairy

goats and cows grazing in the

fields outside the stadium,

where the present swimming

complex is now. They were owned

by Indian milkmen who would

deliver fresh, warm milk to

the doorsteps of neighbourhood

households.”

– Mr Lim Eng Chong, an old boy of

Victoria School, recollecting scenes in

the area in the 1960s and early 1970s.

OPERATION SOOK CHING

Meaning ‘purification through elimination’ in

Chinese, Sook Ching was an attempt by the

Japanese army to ferret out and destroy suspected anti-Japanese elements among the Chinese

population. Three days after the British surrendered on 15 February 1942, the Kempetai or Japanese Military Police ordered all Chinese men to

assemble at designated mass-screening centres

for a dai kensho or ‘great inspection’. At Jalan

Besar Stadium, even women and children were

required to register themselves. New World was

also another Sook Ching site. More than 240 men

who gathered at the Jalan Besar checkpoints

ended up dead in massacres at Tanah Merah and

Changi Beach. As many as 50,000 are thought

to have perished in the islandwide Sook Ching.

The next featured site is located right beside the stadium, and bounded by Tyrwhitt and Kitchener Roads.

23

9 St George’s Avenue

People’s Association Headquarters

(Former Victoria School)

Since 2009, this has been the headquarters of the People’s

Association. From 1985 to 2001, this was the site of Christ Church

Secondary School. But many Singaporeans also have fond memories

of this place as the site of Victoria School from 1933 to 1984. (Please

note that there is no public access to the premises).

Victoria School has its origins in 1876, when school. Bomford's successor, Michael Campbell

Kampong Glam Malay Branch School was found- (principal from 1954-1957), was instrumental in

ed under headmaster Y.A. Yzelman to teach Eng- leading the school to new heights, with several

lish to Malay pupils in Kampong Glam. In 1897, Queen's Scholars, Queen's Scouts and national

this school was amalgamated with Kampong sportsmen. Another fondly remembered princiGlam Malay School (established in 1884 under pal, A. Kannayson (principal from 1966-1971), did

headmaster Abdul Wahab and later, M. Hellier), much to boost morale and oversaw the building

and renamed Victoria Bridge School, with J.H.H. of a new classroom block, canteen, school hall

Jarett as principal. It was located at the junction and science laboratories. The school moved to

of Syed Alwi Road and Victoria Street near the Geylang Bahru in 1984 before shifting to its preVictoria Bridge. Secondary classes began in 1931. sent location at Siglap Link in 2003.

On 18 September 1933, the school moved to

Victoria School is well known for its strong

new premises at Tyrwhitt Road and was renamed academic record and has nurtured many leaders

Victoria School. The school motto Nil Sine Labore in public service as well as the education, legal,

(‘Nothing Without Labour’) was introduced in medical and corporate sectors. Distinguished

1940, followed by the formation of the Old Vic- alumni include former Cabinet member S.

torians' Association a year later. During the Jap- Dhanabalan (b. 1937); Emeritus Professor Edwin

anese Occupation, the school was renamed Jalan Thumboo (b. 1933), Singapore's unofficial poet

Besar Boys’ School. After the war, the school laureate; Professor Ahmad Ibrahim (1916-1999),

premises were briefly used as a hospital. In 1950, Singapore's first non-British Attorney-General;

Victoria School became the first school in Singa- and Dr. Arumugam Vijiaratnam (b. 1921), first

pore to have a dedicated Science block, which Pro-Chancellor of the Nanyang Technological

was planned by headmaster Raymond F. Bom- University and a former national player in hockey,

ford. After his death in 1953, the Bomford Memo- soccer, rugby and cricket. The school also enjoys

rial Fund for outstanding students was estab- a proud sporting tradition. In 1956, sprinter Kesalished to commemorate his contributions to the van Soon, aged 17, represented Singapore at the

Melbourne Olympic Games and was voted the

most popular sportsman in the peninsula that

year. Other notable Victorian sportsmen include

“They always said that Victoria School had

Charlie Chan, who played in the Malaya Cup as

the best football field in Singapore. When

a 16-year old student in 1952, and national soccer

it rained, the field would be drained within

coach Choo Seng Quee (1914-1983).

half an hour. Nearby, there were a lot of

The site was occupied by Christ Church Secshops selling ropes, canvas and hardware.

ondary School from 1985 to 2001. Founded in

1952 as Christ Church School, a private school

These old shops along St George’s Avenue

under the Christ Church Parish at Dorset Road,

have been there since the blocks were built.”

the school came under the aegis of the Anglican

Diocese of Singapore in 1973 and was renamed

– Mr Chow Chee Wing, 63.

Christ Church Secondary School. The school

moved to Woodlands in 2001.

In December 2004, the People’s Association

(PA) announced that it would move into the for›› did you know?

mer Victoria School premises from the former

Three Presidents of Singapore were old boys of

Kallang Airport Building, which it had occupied

Victoria School. They are Mr Yusof bin Ishak (1910since 1960. After restoration and refurbishment,

1970), Mr C.V. Devan Nair (1923-2005) and Mr S.R.

the new headquarters of the PA opened on 29

Nathan (b. 1924).

24

25

“The old building's principal was

my father. I recall spending long

afternoons, sometimes nights, in

Christ Church, waiting for him to

finish sending faxes and shouting at

students. To occupy my time, I used

to dare myself to visit the back end

toilets, which I swear were haunted.

I also remember other times, when

my father would deposit me at Jalan

Besar Stadium. I would watch S.

League games until even being the

only one cheering ironically got

boring.”

– Mr Dan Koh, 24, editor.

“Most of the people in Victoria School

were sportsmen. In those days, the

teachers were very interested in sports.

We had a British lady who was an

Olympic swimmer; that's why we had a

very strong swimming team. The whole

school would be at every single football

game. The esprit de corps was very good.

The school also had very good support

from mechanics in the area, because most

of the children were from the area. So

everytime we had a football match, we had

to close the gates; otherwise, they'd come

in and wallop the opponent team.”

– Mr Kesavan Soon, 73, Victoria School student

from 1953-1958.

FOOCHOW BUILDING

21 Tyrwhitt Road

Foochow (Fuzhou) is the capital of China's Fujian province. Migrants from Foochow, who

speak a dialect called Hockchew, arrived in Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, there are about 120,000 people of Foochow descent in Singapore. Early Foochow

migrants worked in coffee shops or as tailors or

barbers. The Foochow Association was founded in 1910 at Club Street. The six-storey Foochow Association building at Tyrwhitt Road was

built in 1974 and jointly developed with the Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants

Association.

SOURCE: VICTORIA SCHOOL

January 2010. Founded on 1 July 1960 after Singapore attained internal self-government on 3

December 1959, the PA’s mission was to foster

racial harmony and social cohesion in a new

nation through islandwide community centres

that provide common social and recreational

spaces for Singaporeans of all races and religions.

The PA is also the organiser of the annual Chingay

street parade, which came under its purview in

1973. Chingay processions organised by Chinese

clans and temples began in Singapore in the 19th

century. The first modern Chingay parade, coorganised by the PA and National Pugilistic Federation, took place on 4 February 1973 and

involved 2,000 participants who marched from

Victoria School to Outram Park. Since then, Chingay has grown from a largely Chinese procession

featuring lion dancers and martial artists into a

multi-ethnic showcase of performing groups.

If you find the premises similar to the civic

buildings around the Padang, it is because they

were both designed by Frank Dorrington Ward (b.

1885), then Chief Architect of the Public Works

Department. The original main school building,

hailing from 1933, is a neoclassical edifice with a

long frontage and upper-storey corridor. This

block, along with a hall-cum-canteen added in

1967 and the school field, has been conserved and

restored as part of the PA’s headquarters.

HINGHWA METHODIST CHURCH

93 Kitchener Road

This church was founded in 1911 by Reverend Dr.

W.N. Brewster, a missionary who worked in

Fujian province and later came to Singapore. In

1933, the church, which began with a congregation of 21 Hinghwa speakers, acquired a shophouse at Sam Leong Road which was converted

into a place of worship. The current site was

obtained in 1941 with financial aid from the

Methodist Church in America. An earlier twostorey building was replaced by the present

four-storey facility in November 1986. Today,

the church holds services in English, Hinghwa

and Mandarin.

Next, walk up Tyrwhitt Road until you reach the junction of Horne Road, then turn right. The next featured

site, Holy Trinity Church, is located at the junction of Horne and Hamilton Roads.

27

1 Hamilton Road

Holy Trinity Church

Anglican Chinese services in Singapore could possibly trace their

origin to 1856, when a stirring Whitsunday sermon by Revd William

Humphrey of St Andrew’s Church (now St Andrew’s Cathedral)

aroused interest in setting up local congregations. St Andrew’s

Church Mission was later established and grew in strength following

the arrival of Revd William Henry Gomes (1827-1902), a missionary

who had served in Sarawak and who spoke Tamil, Malay and Dyak, in

1872. Revd Gomes later learnt Hokkien in Singapore.

Foochow-speaking mission work began in 1902 tus in 1958. The Foochow Parish and the Hokkien

under the leadership of Revd R. Richards. In 1910, Parish eventually formed the Holy Trinity Parish

Revd Dong Bing Seng (1871-1961) was engaged in 1984.

from Foochow, China, to work with the Foochow

Built with Chinese-style green tiled roofs and

congregation in Singapore. In 1927, Revd Ng Ho decorative elements, the church was designed by

Le arrived from Penang to serve the local Hok- Ho Kwong Yew (d. 1942) in a vernacular Art

kien-speaking community. Services in the Foo- Deco style intended to make it easier for locals to

chow and Hokkien dialects were held at St Peter’s relate to the building. A versatile architect, Ho

Church in the compound of St Andrew’s School was also the designer of the futuristic Art Deco

at Stamford Road.

house of Aw Boon Par at Tiger Balm Gardens

The Stamford Road site was acquired by the (now Haw Par Villa). Unlike most churches, the

government in 1937 for the building of the former altar and nave (where the services are held) were

National Library (which was in turn torn down in located on the second level. The ground floor

2005). The Foochow and Hokkien worshipers housed an assembly area with a stage, which

then moved to Hamilton Road, where the present served as a kindergarten from 1953 until the

building was completed and dedicated on 1970s. A new five-storey Annex Building behind

20 July 1941 by the Venerable Graham White (d. the original hall was completed and dedicated by

1945), Anglican Archdeacon of Singapore. The the Most Rev. Dr. John Chew, Bishop of the AngliFoochow assembly became the first Chinese can Diocese of Singapore, on 24 July 2011 during

congregation in Malaya to be granted parish sta- the Church’s 70th Anniversary Service.

28

29

2 Beatty Lane

Thekchen Choling Temple

Today, this corner of Beatty Lane

and Tyrwhitt Road is occupied

by a Tibetan Buddhist temple

called Thekchen Choling

(meaning 'Great Mahayana

Dharma Temple').

WORLD WAR I NAMES FOR

RECLAIMED STREETS

The new roads created around the Jalan Besar Stadium in

the 1920s were named after leaders of the Great War in

August 1929.

Established in 2001 by Lama Thubten Namdrol

Dorje (born Felix Lee), the temple is open 24

hours a day and has attracted many younger devotees to its prayer sessions as well as Dharma

(the teachings of Buddha) classes held in both

English and Mandarin.

The temple and its followers are also active in

community outreach, providing healing services,

tuition to students in the Jalan Besar area and

distributing food to poorer families during major

festivals.

There is a small statue of Ji Gong (a 12th century Taoist monk revered as a folk deity) in the

temple hall, which is a reminder of its origins as

a shrine called Chee Kong Tong Temple. This

temple was built in 1939 by a migrant from

Shanghai who had originally set up a small altar

near the front gates of New World. There were

many statues of Ji Gong made from wood and

ceramic in the former Chee Kong Tong Temple.

Another temple to Ji Gong, Leng Ern Jee, can be

found at Jalan Rajah off Balestier Road.

ALLENBY ROAD

» after Field Marshall Edmund Allenby

KING GEORGE’S AVENUE

» After King George V of Britain

CAVAN ROAD

¾X]k\i=i\[\i`ZbIl[fc]CXdYXik#('k_<Xic

of Cavan and British Commander-in-Chief

of the Italian Front

FOCH ROAD

» after Marshall Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Commander

of the Allied Forces

FRENCH ROAD

» after Field Marshall Sir John French

HAMILTON ROAD

» after Sir Ian Standish Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief

of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force

HORNE ROAD

» after Sir Henry Sinclair Horne, Commander of the

British First Army.

JELLICOE ROAD

» after Admiral John Jellicoe

MAUDE ROAD

» after General Sir Frederick Maude

MILNE ROAD

¾X]k\iCfi[8c]i\[D`ce\i#D`e`jk\if]NXi

PLUMER ROAD

» after Field Marshall Herbert Charles

Onslow Plumer

TOWNSHEND ROAD

¾X]k\iDXafi>\e\iXcJ`i:_Xic\jM\i\=\ii\ij

Townshend of the British Indian Army

TYRWHITT ROAD

(originally Fisher Road, renamed in 1932)

» after Admiral Sir Reginald Tyrwhitt

After exploring Tyrwhitt, Hamilton and Cavan Roads, walk northwards until you reach Lavender Street.

30

HAMILTON ROAD:

A SHORT HISTORY

In 1925, new streets were cut through the former swampland bounded by Lavender Street,

Syed Alwi Road, Rochor River and Jalan Besar

during the planning stages of the Jalan Besar

Stadium. The Municipality later decided to

name these roads after First World War military heroes. Two exceptions were Penhas

Road and Jalan Boyan. Penhas Road was

named after Rahmin Penhas (d. 1946), a

wealthy Jewish merchant who was the first

developer of the area, submitting plans for

three shophouses along Lavender Street in

1928. Jalan Boyan (now expunged) was

named after a former Boyanese village at the

location of the public housing flats on King

George's Avenue.

A man named Seah Koon Teck was the first

owner to develop buildings by Hamilton Road

in 1931. These 14 two-storey shophouses (1541 Hamilton Road) were designed by an Arab

architect, H.D. Ali, in a neoclassical style with

tile roofs, tripartite louvered windows and fanlike ventilation slots. The second group of

32

buildings was a row of six two-storey shophouses (32-42 Hamilton Road) designed by

J.M. Jackson for owner Pana Noor Mohamed

bin Pakir Mohamed. Two of these shophouses

have been converted into the Hotel Hamilton.

Later, Woo Mon Chew (1887-1958), a

prominent granite and carpentry contractor,

developed two facing rows of three-storey

shophouses (3-11 and 8-30 Hamilton Road),

which were among the first reinforced concrete shophouses in Singapore. Designed in

the Art Deco style by architect Chung Hong

Woot (1895-1957), the buildings have thin

projecting concrete overhangs and horizontal

parapets that convey a sense of continuity.

The centre of the larger block has a pediment

(a triangular section) and balconies that span

two units. Stepped pediments topped by flagpoles book-end each block.

During the Second World War, one of the

shops was converted into a civil defence fire

station. Civilians took refuge in the five-foot

way and fled to the safety of the reinforced

concrete building. Mr Woo fed these refugees

and as a result, the road became colloquially

known as ‘Woo Mon Chew Road’. There is a

Woo Mon Chew Road in Siglap, which was

paved by Mr Woo and where he built a house.

After the war, car repair workshops and

mechanics moved into the neighbourhood,

but moved out in the 1970s. Today, hardware

businesses and coffee shops dominate the

five-foot ways of the area, which was conserved in 1991.

Nearby, the former foundry of Kwong Soon

Engineering still remains at 2 Cavan Road.

Founded by Ching Pak Seng in 1933 as a maker of rubber mangles (machines used to create flat sheets), the company entered the

ship-repair sector after the war, becoming the

first Chinese-owned establishment to break

into the hitherto European monopoly.

"In early 1942, my grandfather moved

his family from a home in the outskirts

of Singapore to the shophouses. He had

hoped for the protection of the British

Army stationed in the city. By late

January 1942, Singapore was under

intense air attack. Ironically, the area

around Hamilton Road was heavily

attacked because the Army had stationed

in the Victoria School by the stadium."

– Woo Pui Leng (b. 1953), an architect and

granddaughter of Woo Mon Chew who lived at

Jalan Besar and Hamilton Road from the 1950s

to 1980s. She is also the author of 'The Urban

History of Jalan Besar', a book published by the

URA in 2010.

›› did you know?

Woo Mon Chew was a former chairman of the Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital. He owned a number of granite quarries,

including the former Woo Mon Chew Granite Quarry (now Pekan Quarry) at Pulau Ubin, which is about 10 minutes

nXcb]ifdk_\m`ccX^\a\kkpXe[efnX_fd\kfdXepjg\Z`\jf]Y`i[j%

33

SOURCE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE.

Lavender Street

Until the mid-20th century, the hinterland beyond Lavender Street

was a vast tidal basin fed by the Kallang River. Originally named

Rochor Road in 1846, this was a dirt track flanked by brick kilns and

vegetable gardens. Urine and night soil (human waste collected

from households in buckets) were used to fertilise the crops, making

the area one of the most foul-smelling on the island.

In 1858, a resident cynically suggested that the

road be renamed Lavender Street (lavender is an

aromatic shrub), which was accepted. The new

name also avoided confusion with Rochor Road

(now Victoria Street). The Hokkiens called the

street Chai Hng Lai, or ‘Within the vegetable gardens’. It was also known as Go Cho Toa Kong Si or

‘Rochor Big Kongsi’ as the main lodge of a kongsi

or secret society was located nearby. The Can34

tonese called it Kwong Fuk Miu Kai or Kwong Fook

Temple Street, after a now-demolished temple

built in 1880. In Tamil, the street was known as

Kosa Theruvu or Potter’s Street.

In the 1880s, fields around the road were used

for cattle grazing, an activity that led to the building of abattoirs further down Jalan Besar. The

vegetable gardens vanished by the 1910s. But

Lavender Street’s foul reputation carried into the

20th century, when swill collectors would collect

leftovers from houses in the area for mixing with

water hyacinths from the nearby Kallang Basin.

The mixture was fed to pigs.

In 1929, Municipal Commissioner John Laycock (1887-1960) suggested to the laughter of

his fellow Commissioners that new roads off Lavender Street (the area around the present day

Kempas Road) be named after aromatic flowers

such as rosemary and thyme. The proposal was

not accepted.

With the building of the Jalan Besar Stadium

and filling in of the swampland between Lavender

Street and Jalan Besar in the late 1920s, new

shophouses began to emerge along the southern

flank of Lavender Street as well as along Hamilton, Tyrwhitt and Cavan Roads. Many of these

developments were in the Art Deco style that

was becoming popular at that time, which fea-

tured clean lines, simple facades with well-proportioned windows, continuous windowsills and

roof pediments topped by flagpoles. The owners

of these shophouses lived in the upper storeys

with their families or rented out the units to

labourers and dancers from New World.

Today, many hardware suppliers can be found

in the small roads between Lavender Street and

Jalan Besar Stadium. These businesses began

moving into the area in the 1970s, taking over car

repair and motor engineering companies which

had to move out under new zoning rules. Other

industries in the area included the Sinwa Rubber

Manufactory and the National Aerated Water

Company, which manufactured a once popular

soft drink brand called Sinalco. The bottler was

based at Hamilton Road from 1929 to 1955.

Today, its disused plant at 1177 Serangoon Road

is a familiar sight to passer-bys.

35

“In the early 1940s, Lavender Street was a

quiet street where you could see workers from

the factories kicking chapteh in the middle of

the street during lunch hour.”

– Mr Phang Tai Heng, long-time resident of Jalan Besar.

LAVENDER FOOD SQUARE

This food centre was formerly known as Bugis

Square. The old name arose as this was where

many hawkers from Bugis Street moved to after

they were relocated in the 1980s. In 1990, the

open-air hawker centre was redeveloped into a

covered food centre with a layered ceiling and

arched entrances that recall the architecture of

Lau Par Sat in Telok Ayer, and renamed to avoid

confusion with the Bugis area. Stalls selling chicken rice, turtle soup and wonton mee (dumpling

noodles) are among the popular eateries here.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

TAI PEI BUDDHIST CENTRE

Located at the corner of Kallang Road and Lavender Street, the Tai Pei Buddhist Centre was founded by Mdm Poon Sin Kiew or the Venerable Sek

Fatt Kuan (1927-2002), whose mother Chow

Siew Keng (d. 1958) arrived in Singapore from

Guangdong in 1936. Mdm Chow established a

temple at Jalan Kemaman in 1938. After her

mother's death, Mdm Poon took over as chief

abbess and rebuilt the temple as Tai Pei Yuen

Temple. As the ministry grew, the Tai Pei Foundation took over the former Kwong Fook School in

1985 before redeveloping the site in 1990. The

building is used to promote Buddhist teachings

and also houses a childcare centre.

LEE RUBBER COMPANY SHOPHOUSES

161 Lavender Street

In the 1930s, the Lee Rubber Company built a

row of eleven shophouses between Foch and Tyrwhitt Roads, which have been conserved and

retain their originate Art Deco facades with pastel tiles. The plaster figures on the roof pediment

facing Foch Road depict soldiers carrying the

Nationalist Flag of the Republic of China, as company owner Lee Kong Chian was an ardent supporter of the Chinese Nationalist Movement of

Dr. Sun Yat Sen.

Lee Kong Chian (1893-1967) was born in Fujian province, China. He moved to Singapore in

1903 and later worked as a teacher and translator. Tan Kah Kee (1874-1961), the ‘Henry Ford of

Malaya’, then recruited Lee, who was fluent in

both English and Chinese, to manage his rubber

business. Lee later became Tan’s son-in-law and

started his own rubber factory in 1927. Thanks to

prudent business practices, Lee amassed the

cash to buy rubber estates during the Great

Depression, becoming Southeast Asia’s ‘Rubber

King’. He also diversified into pineapple canning,

coconut oil, sawmills and biscuits.

In 1952, Lee established the Lee Foundation to

support educational and cultural causes. Beneficiaries of the Lee Foundation include the Chinese

High School, Nanyang University, Amoy University in Fujian, the National Library, Singapore

Management University and most recently, the

Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research at the

National University of Singapore, which has been

renamed the Lee Kong Chian Natural History

Museum.

Next, walk along Lavender Street past the junction with Jalan Besar until you reach the junction of Serangoon

Road. Turn right into Serangoon Road and you will see the next site, Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital, on the left.

36

37

705 Serangoon Road

Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital

Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital sits on the former site of the Tan Tock

Seng Hospital before the latter moved to its present location off

Moulmein Road in 1909. Both institutions had their origins in a

desire to provide medical care for immigrants to Singapore at a time