Technology Extension: Georgia`s Industrial Extension Service

advertisement

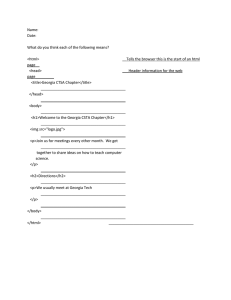

Technology Extension: Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service The Industrial Extension Service at the Georgia Institute of Technology, USA, enables improvements in manufacturing small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by applying proven, commercially relevant technologies previously unknown to the companies. The initiative addresses productivity and competitiveness needs of SMEs that are not served adequately by the private consultancy market. Those that improve become clients for more sophisticated research and development (R&D) by Georgia Tech and hire more qualified personnel, including university graduates. By Juan D. Rogers World Bank, 2013 Introduction The Industrial Extension Service (IES) in Georgia, USA, was created by the government of the state to address perceived weaknesses in the competitiveness of its industrial small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The initiative was in line with the state’s policy to develop the industrial sector of an economy that had been based mostly on agriculture. The technology extension approach contrasted with programs that focused on specific technologies by seeking to transfer available results of research and development (R&D) more generally to the private sector for product development. IES was established in 1960, with the first Industrial Extension Office in the city of Rome, Georgia (Combes 1992), and placed under the responsibility of the Georgia Institute of Technology—the major technologically oriented institution in Georgia—in the state university system. Georgia Tech’s existing Engineering Experiment Station (EES) (later renamed the Georgia Tech Research Institute, or GTRI), became host to the new IES. The need for this sort of service was felt mostly outside of metropolitan Atlanta, in rural areas where technical assistance sources for manufacturing were unavailable. Technical assistance services for manufacturing SMEs do not emerge in response to market forces because the companies are unable to articulate their demand for such services in the market, and supply gravitates instead toward more affluent customers in more sophisticated industries, which in Georgia at that time were concentrated around Atlanta. As the importance of 1 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 manufacturing grew in the state’s economy, especially from the 1940s onward, the tradition of serving the agricultural sector through the agricultural extension service housed at the University of Georgia, the other major university in the Georgia system, inspired the possibility of providing analogous services to the manufacturing SMEs. This represented a natural extension of the role state universities already played in the regional economy. The public engineering schools felt especially compelled to demonstrate their relevance for the local economy by engaging in these activities. An important institutional difference, though, was that the established agricultural extension programs in Georgia and elsewhere were well recognized and had become integrated into a network of services to agriculture supported by the federal government as well as the states. While the newly conceived industrial extension services aspired to reach the same level of prominence and support, they had to proceed without it and it would be a long time before they were to receive recognition as viable, national-level policy priorities, or gain enough political traction for Congress to support a national-level industrial extension program. These programs remained constrained by the states’ interest in supporting them and their ability to do so. Four years before Georgia’s first IES office was established, the EES created its own Industrial Development Branch (IDB) that focused on supporting the industrial development policies of the state by studying obstacles to and opportunities for industry, as well as on helping local governments attract industries to their areas. Its studies identified the needs of prospective newcomers and matched them with available resources to make a case for their recruitment. The leader of IDB at the time, Professor Kenneth Wagner, included in a comprehensive study a proposal to create the IES program by following the model of support offered to small farmers by the agricultural extension service. IES, then, was not the result of systematic analysis of factors leading to the diagnosis of a situation for which it was the solution. Rather, it emerged from a confluence of the state’s economic development policy priorities, focused on attracting and supporting industry; the role Georgia Tech understood itself as playing, as the major engineering institution in the state university system; and the vision of individual leaders who articulated the specific way in which this role should be carried out. In the years since it began, the program has grown in size and sophistication and developed its own analytical capabilities. It has conducted studies and evaluations showing the nature of the needs of industry in the state and guided the adaptation of its services to those changing needs.i A few years after the first office initiated its services, Kenneth Wagner observed that these services had made the difference between success and bankruptcy for many small manufacturers (Wagner 1963, cited by Combes 1992, 65). Several risk factors threatened the success of IES and were overcome at different stages of its development. First, its approach to providing services in the field was critical. The mere availability of information was not sufficient to help companies address their problems; they needed direct help in articulating their needs and interpreting the nature of available solutions for their particular situations. The program risked not meeting this need if it adopted a classical 2 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 academic perspective, which would make it no more than a source of available best practices that companies should adapt to their circumstances on their own. Second, the quality of the field engineers responsible for assisting the companies was also very important. These professionals had to be experts not only in how plants worked, but also in how to earn and keep the trust of company owners and managers, who were often very skittish about opening up their operations to external scrutiny. Third, sustaining these services required adequate financial support, with public support critical to maintaining the public service focus of the program’s mission. Being forced to survive on a purely commercial basis as a fee-for-service entity would risk gravitation to wealthier customers instead of the intended target of SMEs affected by market failure. The initial hope was that support for the services would diversify and grow with the creation of federal programs to supplement state support. As mentioned above, this did not materialize for a long time. The state government kept its commitment to the program, however, and it remains in operation to this day – albeit with more diversified support, which commenced about three decades after it began. Program design The rationale behind the design of IES is similar to that of agricultural extension, which, as mentioned, was well established at the time of IES’s creation and a direct inspiration for its early proponents. The program focuses on a transfer of tacit knowledge that can only be done through direct interpersonal collaboration. In this way, it introduces companies to existing solutions that are new to them. The opportunities of these firms to communicate with companies that already apply the technologies are limited by their size, limited excess resources, and small client and supplier bases, among other conditions known to affect SMEs in less developed regions. Two main design elements, derived from the model of agricultural extension services address these limitations: first, a field engineer works directly on site with the companies that receive assistance, and, second, field agents are distributed across the region where most manufacturing SMEs are located. These modes of service delivery enable the services to reach target companies easily and be proactively available to them. IES differed at first from agricultural extension services with respect to the content of the technical assistance offered. Agricultural extension connected farms with results of R&D done at the land grant universities for farming improvement. The technology transfer role in these services was clear. In contrast, the approach of field engineers to process improvement and problem solving was more generalist. During the early stages, the program most commonly rendered assistance to regional small manufacturers with plant layout and cost structures— topics not at a level of sophistication which required engineering R&D conducted at the university’s research labs. Later, firms that received extension services and improved enough to adopt new technologies in processes and products did engage in technology transfer from university R&D. This link with R&D did not become the entry point for extension services, however. 3 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 IES is clearly proactive in its approach; it does not simply wait for firms to come and request its services. The program has made significant efforts over the years to reach out to the target firms, beginning with opening offices off campus in areas of the state where significant concentrations of manufacturing firms were in need of improvement. Second, the field engineers leading these offices were recruited for their familiarity with the target firms and ability to communicate and establish relationships of trust with them. Third, the program launched an effort that grew over time in variety and sophistication to make contact with target firms and inform them of opportunities available through its services. For instance, field engineers would often reach out to firms and organize events to showcase their offerings. The initial services focusing on fundamental industrial engineering techniques applied to plant layout and organization of production were heavily dependent on the particular expertise and experience of the field engineers. New services were added later, especially after the creation, a little over two decades after the start of the Georgia Tech IES, of a national extension program, the Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), housed at the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST).ii, iii The new services, now commonly recognized as typical for IES, included the array of interventions classified as “lean process improvement.” According to the Georgia Tech center, Lean, a system for continuous process improvement, was developed primarily from the Toyota Production System (TPS), and helps to shorten the order-to-cash cycle by defining what is value according to the customer and organizing and improving processes to deliver what is needed, when it is needed and with minimal waste.iv Other interventions identified under the “lean” production label include 5S, which stands for sorting, setting in order, systematic cleaning, standardizing, and sustaining, and Kaizen, a method that uses “rapid process improvement” events to assess, train, and take action on any aspect of the business. Services added over time have included assistance with sustainability (improvement of environmental management or compliancy with new environmental regulations); energy management; certification from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO); quality management; product development; and brand management.v Since Georgia Tech IES was designed as a public service offered by a public university, the costs of offering its services have been partly covered by public subsidies. During the early stages, public support only came from the state government. The proportions of costs covered by the subsidy and the contribution by companies did not conform to any fixed overall formula. However the design offered a free first consultation and diagnosis, which are in place to this day. With the advent of the national program, an overall target was established for overall annual center budgets with national subsidy, state subsidy, and customer fees comprising onethird each. These proportions still apply with respect to the overall financing of the center. In terms of individual customers, the cost covered varies with the nature and size of the projects. As their improvements gain momentum and they profit from them, they are required—and are more willing—to cover more of the cost. The program was shaped in the context of the state and its economy. States in the southern United States were more similar to developing nations than they were to the industrialized 4 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 states in the Northeast and West. Their position relative to the rest of the country was disadvantaged as they struggled with changes from a predominantly agricultural and extractive economic structure to one in which manufacturing had a more important role. Even as these states industrialized, beginning in the 1930s and advancing more steadily in the 1950s and ’60s, they lagged in sophistication, productivity, and general competitiveness. Program designers reasoned that the close relationship that had been so successful in supporting small farmers was also the appropriate approach for supporting small manufacturing companies. In other words, rather than being the conclusion to an analytical process, the choice of design was based on the intuitive sense provided by experience. Implementation Process The first field office that opened in Rome, Georgia, was funded with $30,000 from the governor’s office and $75,000 from the Coosa Valley Planning and Development Commission. The community also contributed by subsidizing the use of a building and offering other in-kind support. From 1964 to 1966, IES opened another seven offices in six cities across the state: Carrollton, Albany, Brunswick, Savannah, Augusta, and Macon.vi Each was staffed with one or two field engineers who were familiar with industry in the region and generalists in their approach to industrial extension. During this period, the program relied on the expertise of the field engineers. Those hired had backgrounds from industries prominent in the regions in which they were to work. They mostly offered plant layout services and did “evaluation” through paper surveys, which one of the field managers took around in a booklet to show to state legislators. The experiences recorded by field engineers were very effective in convincing policymakers and lawmakers that the program was valuable to their constituencies and solidified their commitment to continue funding it. Once Georgia Tech joined the federal government’s MEP, IES had to adopt more standardized approaches that included techniques learned from Japanese manufacturing best practices, as described above with reference to the Toyota Production System. The variety and scope of the projects undertaken with clients grew with the center and its menu of services. The typical project today is initiated either with a visit by a field engineer or a request from a firm that has heard from other businesses about the benefits IES might offer it. The first stage is a diagnosis, which typically involves a one-day visit by a field engineer to gather information and observe the operation of the firm, followed a few days later by a report of the results. This stage is always free to SMEs in the region. The diagnosis contains suggestions for an improvement project the firm might undertake. Early on, as mentioned before, benchmarking and recommendations for more efficient layout of manufacturing processes were the main projects undertaken. More recently, any facet of the business might be the key target for an improvement project. Depending on the scope of the changes and how much training is needed by personnel, projects might last from a few weeks to 5 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 about a year. Many companies are repeat customers, engaging in sequences of projects over several years that generally become more sophisticated as their capabilities increase. Georgia Tech competed for NIST's MEP in the first and second rounds of national opportunities without success but was finally successful in 1993, with a proposal submitted under the Technology Reinvestment Project (TRP).vii In the 1990s, the IES and other industry services, such as incubators and startups, were combined in the Economic Development Institute, a new university unit outside of GTRI. This unit has continued to diversify its linkages with industry, which are no longer limited to IES but still include it as a key component. Timeline of evolution of industry services The evolution of industrial extension implementation at Georgia Tech and its relationship to other industry support activities, programs, and policies at the state and federal levels are set out in the following timeline, which extends from the early years of the university to the late 1990s.viii Box 1. Georgia Tech Industrial Extension Implementation Timeline Early years of the university (1885–1930s) 1885 1919 Georgia Tech established by legislature; about 3,000 manufacturers are in Georgia. Engineering Experiment Station (EES) at Georgia Tech created on paper by state legislature in anticipation of federal funding bill for such research centers (which never comes through). Responsibilities include “encouragement of industries and commerce.” Emergence of state-level industrial development policies (1940s–70s) 1946 EES uses matching state funds for regional economic analyses, conducted to identify opportunities for new industry and later used by industrial developers for recruiting. Industrial Development Branch (IDB) of EES formed—the first time industrial development research at EES is specifically budgeted for. Georgia Assembly passes bill replacing 1919 EES legislation and creating an Industrial Extension Service (IES) within the IDB, to be administered through local EES field offices. IDB funding reaches $330,000 ($180,000 state and $150,000 contracts with private firms). Industrial Services Branch created, formally starting the program of technical assistance to industries. First field office opens in Rome with $30,000 from governor and $75,000 from Coosa Valley Planning and Development Commission. IDB budget $500,000+; federal funds also used. 8,623 manufacturers are in Georgia. 1956 1960 1961 1966 1977 Expansion of programs to include startup and innovation support (1980s–90s) 1980 Advanced Technology Development Center (ATDC), a high-tech incubator, started on the Georgia Tech campus. EES becomes Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI). 1985 6 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 1990 Georgia Research Alliance (GRA), a nonprofit partnership among business, government, and research universities, founded to develop science and technology–based industry, commerce, and business. IES programs reorganized into the Economic Development Institute (EDI), along with ATDC. Center for International Standards and Quality (CISQ) established at EDI. Successful MTC proposal submitted under the Technology Reinvestment Project (TRP). With federal funding, IES joins the NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership (U.S. Department of Commerce), incorporating new name—the Georgia Manufacturing Extension Alliance (GMEA)—and expanding to 18 offices. 10,517 manufacturers are in Georgia. 1993 1994 1995 New programs in the twenty-first century 2000s Commercialization program launched to grow companies and jobs from research innovation. Strategic Partners program launched to expand national and global corporate partnerships for Georgia and Georgia Tech. The timeline illustrates how the university provided more services to industry over time around the original extension program, with a significant diversification of university–industry linkages developing. It is interesting to note that the extension service predates most of the other, betterknown interactions, such as R&D collaboration or university support for high-tech startups. The timeline suggests the university learns much about the needs of industry and the variety of opportunities and ways to have an impact on the economy, beginning with the less glamorous and sophisticated technology extension services. Current Technology Extension Approaches and Services According to the current website presentation of Georgia Tech’s industrial extension services, the purpose of technological extension is to do the following: Improve the competitiveness of Georgia’s small & mid-sized manufacturing firms through growth strategies, process improvement and sustainable actions. Provide “on-site” technical assistance and continuing education to firms throughout the state. Increase federal & state government contracting revenue for Georgia firms.ix This last function is a rather recent addition. The need to meet requirements for becoming a government supplier of various products or services is an important motivation for engaging in process improvements with a clear market objective in sight. The program has also facilitated the creation of the Georgia Tech Lean Consortium, initially a group of 12 companies in South Metro Atlanta that work together to advance the knowledge of “lean system thinking” for continuous improvement of their manufacturing processes. Groups are also expanding to Augusta and the northwestern and northeastern regions of Georgia, and they carry out benchmarking activities and periodic workshops and share events to facilitate joint learning. 7 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 Manufacturing in Georgia currently comprises over 10,000 firms with over 500,000 employees. The service focuses on firms with 20–250 employees, roughly a third of the total population of manufacturing firms in the state. This very diverse industrial base includes printing, fabricated metal products, food processing, textile products, chemicals, and automotive supply firms, among others. More than half are located in the Atlanta metro area. Results The performance of Georgia Tech’s IES, called Georgia MEP (GaMEP) since it qualified to become part of the national MEP program, is measured by tracking several indicators of improvement in the firms it assists: Increased sales Reduction in operating costs Jobs created or retained Increased investment These are complemented by some activity indicators that reflect the reach and volume of activity of the program and the cost to public sources of its activities, and some impact indicators at the state level: Number of companies served Number of projects completed Amount of public funding per project Amount of public funding per company served Increased tax revenues traceable to company improvements Some of the latest figures for these indicators are as follows:x 1,770 manufacturers served in 2012 $36 million in reduced operating costs $191 million in increased sales 950 jobs created or retained $6,250 average public funding per company servedxi These indicators are based on ongoing information gathering from client firms. No evaluations of the IES include control groups or any other experimental or quasi-experimental arrangement to distinguish clearly the effects of these services from those of other factors that may be present in the region at the same time. At the national level, a few studies have been conducted to establish the impact of support from MEP centers on firms across the country. For example, Jarmin (1999) found that assisted companies increased their productivity between 3.5 percent and 16 percent more than unassisted companies during the same period. Other studies (Ordowich et al. 2012) have produced mixed results. The Georgia Tech Enterprise Innovation Institute, where the extension service is now housed, conducts a survey of manufacturing in Georgia every two years, but it does not benchmark the effect of the extension service at Georgia Tech or measure its additionality.xii 8 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 Results are also indicated by success stories. A few examples follow.xiii Box 2. IES Illustrative Success Stories Success Story #1: Roper Pumps Intervention: Lean manufacturing and 5S Results: Realized a cost savings of $18,000 per year Reduced changeover time by 55 percent Reduced lead time from 18 days to 8 days Reduced travel time of materials and parts in the plant by 450 feet daily Testimonial: “Georgia Tech has a host of wonderful programs, and if you look at the cost of getting this highly professional experience, I don't know how anybody can turn it down. The value is outstanding. The biggest worth is [in] the overall culture change Georgia Tech has helped bring to Roper Pumps.” Jim Simonelli, Vice President, Business Development Success Story #2: Lighting Manufacturer—Lean implementation has resulted in doubling of productivity, 80 percent reduction in setup time, and 30 percent reduction in inventory. Success Story #3: Refrigeration Manufacturer—Energy Efficiency Company has implemented 90 percent of GT recommendations and reduced energy usage by 1 million kilowatt hours per year. Success Story #4: Pump Manufacturer—Product development assistance has added 12 new product ideas to the development pipeline. Success Story #5: Hospital Emergency Room—Lean Healthcare has resulted in 44 percent reduction in patient time, improved patient satisfaction, and reduction in staff turnover. The Georgia Tech Industry Extension Service has had effects beyond the immediate results of its activities. By the time the national MEP was created in the U.S. Department of Commerce, it was largely viewed as a model to be replicated in other states. It also positioned Georgia Tech in the region as a credible source of industry-relevant information, technology, and experience. As Youtie and Shapira report (2008), the university has become an innovation hub in the region, due in great measure to the close relationship it has developed with regional industry through the IES. Lessons learned Lessons can be learned from this case in several areas: 9 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 First, staffing and human resources are critical to success. The best results in technology extension are obtained through face-to-face interaction between field engineers and managers and workers at the companies, for which the field engineers must have industrial technology and business expertise plus interpersonal skills. Different models of staffing are based on local human resources availability. Some combination of permanent staff with networks of external consultants who provide specialized services appears to be the norm. The challenge to finding the right people changes over time. Initially, the field engineers are experienced engineers who have worked in industry in the region for a number of years and are ready to “give back” to the business community. With an ongoing program, opportunities for training future field extension engineers emerge. Second, geographical coverage and service points matter. The program model was successful in great measure because the program was decentralized and distributed across the state. To develop trust in partnerships and relationships with companies and to facilitate delivery and awareness of services, it is sensible to locate offices close to agglomerations of firms and acquire specialized knowledge that relates to their needs. Targeting both individual firms and groups for a balance of intensity and breadth in the impact of services is important. Core services are delivered mostly one on one, but new value-added services may be delivered to groups of companies or networks. Relationships of trust developed through individual projects enable the extension engineers to facilitate the formation of groups and allay fears of revealing sensitive information to competitors. Currently, four lean consortium groups are operating in different parts of Georgia.xiv Third, public funding is invariably present. The different models of funding for offices and centers all include some public funding. The premise is that providing technology extension services is a public service mission. Without this component, the market failure that motivates the creation of these programs would not be addressed. In general, the size of the budget will be related to the number of clients served. Several caveats apply, having to do with the mixture of services a program offers to individual firms or groups. Government budget cuts force a tradeoff between having more services offered to a few and keeping the subsidized targets due to market failures. There is increasing pressure from external sources of funding to become selfsufficient, which usually means services move up-market to target larger, wealthier firms. Fourth, providing services is not equivalent to providing funding. Technology extension service providers evolve to offer a highly diverse mixture of nonmonetary services, including R&D, process improvement, technical assistance, testing, and training, as the needs of the target firms evolve. Other public agencies may complement with funding. Fifth, a tradeoff between greater coverage and greater impact is ever present. Pressure to increase coverage usually leads to standardized services, which usually have less impact than customized ones. Customized services generally require more staff time and lead to less coverage. Sixth, systematic evaluation is uncommon but important. Activity reporting is more common than systematic independent evaluation. In a few cases, formal evaluations are conducted periodically. This has been true of Georgia Tech since the late 1990s. The design of and 10 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 approach to evaluation differ, however, depending on whether its purpose is to justify the program or to learn about and improve it. Endnotes i Reports can be found at http://www.gms-ei2.org/. ii A history of the attempts to organize a national technology extension program is beyond the scope of this case study. The Manufacturing Extension Partnership still exists, and the agency that manages it, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), is in the U.S. Department of Commerce. The program is called a “partnership” because it does not have centers of its own and requires a financial commitment from the state or local government to cover at least a third of the participating centers’ budget. Centers across the country must meet a standard set of requirements to be certified into the program and receive a partial subsidy for their operations. iii Source: http://gamep.org/services/lean-process-improvement/, accessed July 15, 2013. iv Detailed explanations of the content of these services can be found at http://gamep.org/services/. v The Technology Reinvestment Project (TRP) was a Clinton Administration program designed to repurpose the technology development effort that had lost some of its relevance with the end of the Cold War and apply it to the civilian economy, to create jobs and increase the competitiveness of the U.S. economy. Some of the funding received by the U.S. Dept of Commerce under this program was assigned to the MEP. vi The Carrollton office was funded in part by the U.S. Department of Commerce under a national program that was created at the time but did not survive as long as the service offices did, namely, the Area Redevelopment Administration (ARA), which later became the Economic Development Administration. vii Source: http://web.archive.org/web/20040902152450/http://cherry.iac.gatech.edu/sim/refs/gmeahist.htm, accessed June 8, 2013. viii Ibid. ix Quoted from the industry services web page http://innovate.gatech.edu/industry/, accessed June 9, 2013. x Source: http://innovate.gatech.edu/programs/manufacturing-extension-partnership-gamep-enterpriseinnovation-institute-at-georgia-tech. Accessed June 8, 2013. xi This amount has remained very steady over the last 20 years and is very close both to the average amount of public funds per project and the national average per client served, fluctuating between $6,000 and $7,500 nationally. xi i Survey reports can be found at http://www.gms-ei2.org/. xiii An archive of success stories can be found at http://innovate.gatech.edu/success-stories/, accessed June 9, 2013. xiv See http://gamep.org/news-and-resources/lean-consortium/. 11 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013 References Combes, Richard. 1992. “Origins of Industrial Extension: A Historical Case Study in Georgia.” MS Thesis in Technology and Science Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA. Georgia Tech Enterprise Innovation Institute. www.innovate.gatech.edu. Georgia Manufacturing Survey. http://www.gms-ei2.org. Jarmin, Ron S. 1999. “Evaluating the Impact of Manufacturing Extension on Productivity Growth.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 18 (1): 99–119. Ordowich, C., D. Cheney, J. Youtie, A. Fernandez-Ribas, and P. Shapira. 2010. “Evaluating the Impact of MEP Services on Establishment Performance: A Preliminary Empirical Investigation.” Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, CES 12-15. http://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2012/CES-WP-12-15.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013. Wagner, K. C. 1963. “A Preliminary Blueprint for Industrial Development in Georgia.” Report to the Industrial Development Division. Georgia Tech Engineering Experiment Station. Wyckoff, A., and L. Torntzky. 1988. “State Level Efforts to Transfer Manufacturing Technology: A Survey of Programs and Practices.” Management Science 14 (4): 469–81. Youtie, J., and P. Shapira. 2008. “Building an Innovation Hub: A Case Study of Transformation of University Roles in Regional Technological and Economic Development.” Research Policy 37: 1188–1204. 12 Georgia’s Industrial Extension Service World Bank 2013