The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of

advertisement

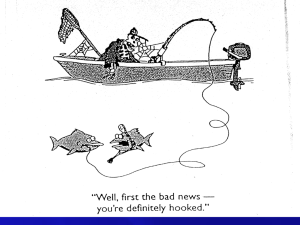

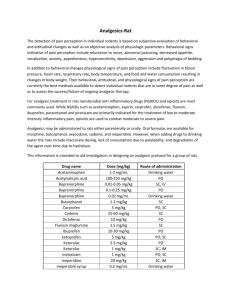

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone—experience from a medium-sized Finnish City Hanna Uosukainen, MSc. a,⁎, Hannu Pentikäinen, M.D. b, c, Ulrich Tacke, M.D., Ph.D. a, b a b c University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio Campus, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 1627, FI-70211 Kuopio, Finland Addiction Psychiatry Unit, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland Health Care Services, Criminal Sanctions Agency, Kuopio, Finland a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 24 September 2012 Received in revised form 10 January 2013 Accepted 18 January 2013 Available online xxxx Keywords: Buprenorphine Naloxone Diversion Electronic monitoring Opiate substitution treatment a b s t r a c t Providing unobserved opioid substitution treatment (OST) safely is a major challenge. This study examined whether electronic medicine dispensers (EMDs) can reduce diversion of take-home buprenorphine–naloxone (BNX) in a medium-sized Finnish city. All BNX treated OST patients in Kuopio received their take-home BNX in EMDs for 4 months. EMDs' effect on diversion was investigated using questionnaires completed by patients (n = 37) and treatment staff (n = 19), by survey at the local needle exchange service and by systematic review of drug screen data from the Kuopio University Hospital. The majority of patients (n = 21, 68%) and treatment staff (n = 11, 58%) preferred to use EMDs for the safe storage of tablets. Five patients (16%) declared that EMDs had prevented them from diverting BNX. However, EMDs had no detectable effect on the availability or origin of illegal BNX or on the hospital-treated buprenorphine-related health problems. EMDs may improve the safety of storage of take-home BNX, but their ability to prevent diversion needs further research. © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Buprenorphine is a widely used, effective and safe opioid substitution treatment (OST) medicine (Johnson, Jaffe, & Fudala, 1992; Ling et al., 1998; Kakko, Svanborg, Kreek, & Heilig, 2003). Buprenorphine has enabled the provision of OST in office-based settings as well as in primary health care (Fudala et al., 2003; Lintzeris, Ritter, Panjari, Clark, Kutin, & Bammer, 2004; Auriacombe, Fatseas, Dubernet, Daulouede, & Tignol, 2004; Cozzolino et al., 2006; Fiellin et al., 2008). This allows unobserved dosing which means that patients can receive take-home doses of their OST medicines. Unobserved dosing can offer substantial advantages. These are increased accessibility to OST (Bell, Byron, Gibson, & Morris, 2004; Gunderson, Wang, Fiellin, Bryan, & Levin, 2010) and positive effect on social and occupational rehabilitation (Bell et al., 2004; Anstice, Strike, & Brands, 2009). Retention in treatment is similar (Fiellin et al., 2006; Bell et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2012) or even improved (Holland et al., 2012) in comparison with observed dosing. OST patients value unobserved dosing and consider it as an essential part of OST (Stone Conflicts of interest: HU has received unrelated grant funding from Lundbeck Ltd. HP has received lecture fees and congress expenses from Reckitt Benckiser, Pfizer and Lundbeck Ltd. ⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +358 40 3553 775; fax: +358 17 162424. E-mail address: hanna.uosukainen@uef.fi (H. Uosukainen). & Fletcher, 2003; Treloar, Fraser, & Valentine, 2007; Madden, Lea, Bath, & Winstock, 2008). Diversion of OST medicines is defined as selling/trading, sharing or giving these medicines to others (Larance, Degenhardt, Lintzeris, Winstock, & Mattick, 2011b). Diversion is especially common in treatment with buprenorphine with 24–28% of buprenorphine/ buprenorphine–naloxone patients reporting recent diversion (Winstock, Lea, & Sheridan, 2008; Larance et al., 2011a). Diversion of OST medicines carries the risk of overdoses, dependence as well as injection-related harm (Degenhardt et al., 2008). Increased abuse by injecting has been shown with unobserved dosing of methadone (Darke, Ross, & Hall, 1996; Lintzeris, Lenne, & Ritter, 1999; Darke, Topp, & Ross, 2002; Ritter & Di Natale, 2005; Duffy & Baldwin, 2012). A buprenorphine–naloxone (BNX) combination product was developed (Suboxone) in order to deter the intravenous (IV) abuse of buprenorphine and this was also hoped to prevent its diversion (Bell et al., 2004). However, the addition of opioid-antagonist naloxone does not completely prevent IV-use (Alho, Sinclair, Vuori, & Holopainen, 2007; Bruce, Govindasamy, Sylla, Kamarulzaman, & Altice, 2009) and also BNX diversion has been reported recently (Larance et al., 2011a; Johanson, Arfken, di Menza, & Schuster, 2012). Diversion and abuse of OST medicines jeopardize both the outcomes and the reputation of OST (Mammen & Bell, 2009). The situation in Finland is especially concerning, because the most commonly used OST medicine, buprenorphine, was the main reason for treatment seeking in 33% of all clients with substance use 0740-5472/$ – see front matter © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003 Please cite this article as: Uosukainen, H., et al., The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone— experience from a medium-sized Finnish City, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003 2 H. Uosukainen et al. / Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment xxx (2013) xxx–xxx problems in 2009 (Forsell, Virtanen, Jääskeläinen, Alho, & Partanen, 2010). Due to its widespread abuse, single-ingredient buprenorphine (BUP) was withdrawn from sale and since December 2007 only buprenorphine–naloxone (BNX) has been approved for OST in Finland. Generally, patients receive OST free of charge in Finland with the exception of those who receive their medication from community pharmacies where they may have to make a contribution towards medication costs. Duration of OST depends solely on patient's psychosocial rehabilitation. Take-home allowances are granted to stable and highly motivated patients after several weeks of daily supervised dosing, and from February 2008, clinically stable patients have been able to receive BNX unsupervised from community pharmacies. Various approaches have been introduced to limit the abuse and diversion of opioids, e.g. diaries, contracts, laboratory drug screens (Fishman, Wilsey, Yang, Reisfield, Bandman, & Borsook, 2000), abusedeterrent formulations (e.g. sustained-release, transdermal and sublingual film formulations) (Fudala & Johnson, 2006), prescription monitoring programs (Fishman, Papazian, Gonzalez, Riches, & Gilson, 2004; Pradel et al., 2009) and the use of RFID (radio frequency identification) technology or electronic adherence monitoring (Fudala & Johnson, 2006). So far, previous studies on electronic monitoring in OST have used it to obtain reliable and detailed adherence data (Arnsten et al., 2001; Fiellin et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2007). Our 4-week pilot study examining electronic compliance monitoring in 12 BNX treated OST patients indicated that monitoring was well accepted and subjectively increased compliance (Tacke, Uosukainen, Kananen, Kontra, & Pentikäinen, 2009). After these encouraging results we conducted a larger local intervention with electronic medicine dispensers (EMDs). This study examined whether EMDs can reduce diversion of take-home BNX in OST patients in a medium-sized Finnish city. 2. Materials and methods 2.1. Participants and setting This naturalistic, open-label clinical study was done in Kuopio, a city of 90,000 inhabitants in Eastern Finland. Locally OST is provided by three services: the addiction psychiatry outpatient clinic, the Kuopio region addiction services trust, and the health centre of the Kuopio municipality. All three treatment units as well as local community pharmacies dispensing BNX (n = 3) participated in this study. All OST patients registered at the treatment-services and eligible for the study, were asked to participate. Inclusion criteria for the patients were the following: • diagnosis of opioid dependence (F11.22) according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) criteria; • OST with a stable dose of BNX; • OST started at least 1 month before the initiation of the study; • one or more take-home allowance(s) per week. During the intervention phase, EMDs were provided to all eligible patients as part of the routine clinical care. In this manner, we ensured that in the city of Kuopio take-home allowances of BNX were provided in EMDs regardless of whether the patient consented to participate in the study or not. Participating patients were interviewed (data to be published separately) and asked to complete a questionnaire (see Section 2.4.). 2.2. Electronic medicine dispenser (EMD) The EMD used in the study was the Med-O-Wheel Smart (Addoz Ltd, http://www.addoz.com/products/med-o-wheel_smart/). BNX tablets (maximum of 1 week's dose for the reasons of stability) were removed from blisters and the daily doses were put into the compartments of the dosage cassettes and then inserted into the EMDs. Dispensers were programmed according to patients' individual dosing times. The right compartment with the daily dose could be moved into the opening position by pressing the cover of the device during a 3-hour time window around the preset dosing time. After the time window, EMDs switched into the “closed”-mode automatically and tablets were inaccessible until the next preset time window. Therefore, missed or skipped doses remained locked within EMDs. The device was made of hard plastic and included a locking system to prevent tampering and access to tablets outside the preset time window. Treatment staff (nurses, pharmacists) loaded and programmed EMDs which took approximately 5–10 minutes per device depending on the patient's dose. 2.3. Procedures In August and September 2010 all eligible patients were asked to give their written informed consent. A few weeks later, dispensing of BNX take-home doses in EMDs was started and continued for the next 4 months. In all other aspects of OST, normal standard care was continued, including the possibility for an increase in the number of take-home allowances. All study protocol violations (skipped doses, tampering with the device etc.) were handled individually according to local treatment guidelines with a reduction of take-home allowances as the most usual consequence. The availability of illegal buprenorphine in the city of Kuopio and possible changes due to the trial were examined by an anonymous questionnaire, handed out at the local needle exchange service. All clients, visiting this service during the two 2-week study periods in August 2010 (pre-EMD phase) and in December 2010 (EMD phase), were asked to fill in the questionnaire. Information on the drug screens taken at the Kuopio University Hospital was collected retrospectively and consisted of the time period of EMD use (EMD-phase 1.10.-31.12.2010) and control periods before (pre-EMD-phase 1.7.-31.8.2010) and after (post-EMD phase 1.2.-30.4.2011) the intervention. Samples for the urine drug screens were taken at the emergency department and the intensive care unit at Kuopio University Hospital, which is the only local provider of acute and emergency services. Positive drug screens were regarded as indicators for hospital-treated drug-related health problems. We assumed that any licit or illicit buprenorphine user in Kuopio with an acute health problem requiring hospital treatment would be subjected to a urine drug-screen, if his or her condition was suspected to be drug-related. Drug screens included buprenorphine (with and without naloxone), other opioids (methadone, oxycodone, heroin, codeine, morphine), other illicit drugs (amphetamine, methamphetamine, cannabis, MDMA) and benzodiazepines. Urine-samples were analyzed with the Cobas 6000 clinical chemistry analyzer (Roche/ Hitachi) at the Eastern Finland Laboratory Centre. For buprenorphineanalysis CEDIA Buprenorphine Drugs of Abuse Assay reagents (Thermo Scientific) and the kinetic interaction of micro particles in a solution (KIMS) reagents (Roche Diagnostics) were used. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the North-Savo Hospital District. The Clinical Trials protocol registration number of the study is NCT01182402 (www. clinicaltrials.gov). 2.4. Measures At the end of the EMD phase in January 2011 patients were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire to give their opinions on EMDs' potential to prevent the diversion of BNX in general (agree, no opinion, disagree), the safety of its use compared to paper sachets (agree, no opinion, disagree), whether EMDs had prevented them from diverting or others to get hold of their BNX (yes, no) and the possibility of tampering with the device (easy, difficult, impossible). Please cite this article as: Uosukainen, H., et al., The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone— experience from a medium-sized Finnish City, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003 H. Uosukainen et al. / Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Tampering was defined as getting access to tablets in the device outside the time window. A slightly modified version of the questionnaire was distributed to treatment staff (nurses and pharmacists involved in the study) to request their opinions on the same issues and whether they thought EMDs could be used as part of routine OST (agree, no opinion, disagree). Questions in the questionnaire distributed at the local needle exchange service were based on the study by Alho et al. (2007). To ensure the content validity of the questionnaire, it was developed in close collaboration with service-staff (nurses and physicians). For the purpose of distinguishing between buprenorphine products, the abbreviation BNX was used for buprenorphine–naloxone (Suboxone) and BUP for single-ingredient buprenorphine used in OST (Subutex). BUP is only available by special permission from the Finnish Medicines Agency for the treatment of pregnant women. We requested information on the frequency of buprenorphine use and products (BNX, BUP) used during the previous month, the most frequently used product, present availability (good, moderate, poor) and origin (OST versus other) of BNX and amount of money respondents were willing to pay for one tablet of BUP (8 mg) or BNX (8/2 mg). 2.5. Data analyses Mann–Whitney U-test was used for analyzing continuous variables and Pearson chi-square (χ 2) test and Fischer's exact test for categorical variables. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests. Analyses were done with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 19). 3. Results 3.1. Study participants A total of 37 patients (88% of all eligible patients) agreed to participate in the study. Their demographic information is given in Table 1. Five patients refused to participate (four men and one woman). Three patients were pregnant during the study and received their take-home buprenorphine (BUP) in EMDs. A total of 45 persons used EMDs during the study period. One patient claimed that the EMD had been stolen; all other EMDs were returned after the study period. Major damage to the EMD occurred in two cases and several instances of minor damage were recorded. Table 1 Demographic background information of study participants and their opinions on electronic medicine dispenser (EMD) use. Demographics (n = 37) Males, n (%) Age, mean (SD) Caucasian race (Finnish), n (%) Length of opioid substitution treatment (OST) (years), mean (SD) Daily dose of buprenorphine–naloxone (BNX) (mg), mean (SD) Patients' opinions (n = 31) EMD prevented me from diverting OST medicines EMD prevented others to get hold of my OST medicines In general EMD can prevent diversion of OST medicines It feels safer to keep OST medicines in the EMD compared to paper sachet Tampering with EMD is Easy Difficult Impossible Missing answer 21 30.0 37 3.0 (57) (5.1) (100) (2.9) 17.2 (4.3) n (%) 5 (16) 7 (23) 18 (58) 21 (68) 6 (19) 6 (19) 18 (58) 1 (3) 3 3.2. Views of patients and treatment staff Thirty-one patients (84%) completed and returned the questionnaire. Five patients (16%) reported that the EMD had prevented them from diverting their medicines (Table 1). However, 18 patients (58%) thought that EMDs can generally prevent diversion. Twenty-one patients (68%) regarded EMDs as safer option for the storage of takehome doses than paper sachets which had been the routine dispensing practice before the trial. Altogether 19 completed questionnaires (3 from pharmacies, 16 from treatment units) were returned by treatment staff (response rate of 84% estimated according to the number of returned questionnaires and staff involved in the study). Staff did not think that EMDs could prevent diversion (16 respondents, 84%). Nevertheless, 58% of them (n = 11) preferred to dispense take-home doses of OST medicines in EMDs compared to paper sachets and 74% of them (n = 14) reported that EMDs could be used as part of routine OST. 3.3. Survey at the needle exchange service The response rate for the first survey in the pre-EMD phase was 46% (35 responses), and for the second survey in the EMD phase 39% (27 responses). In the first survey three respondents reported that they did not use buprenorphine and they were excluded from the analyses. Respondents in both surveys were mostly males (56% and 64%, respectively) and younger than 30 years old (56% and 74%, respectively). Nearly all respondents in both surveys abused BNX (100% and 96%, respectively), and 47% (n = 15) and 59% (n = 16) of them were daily buprenorphine users (Table 2). In the pre-EMD phase more respondents indicated BNX was their most commonly used buprenorphine product (n = 26, 87%) compared to the EMD phase (n = 16, 59%), (p = 0.033). There were more users of illegal BUP in the EMD phase than in the pre-EMD phase (67% versus 47%, p = 0.188). According to the views of respondents the availability of illegal BNX (p = 0.371) and its origin from OST (p = 1.000) did not change between the surveys. 3.4. Drug screens During the data collection periods altogether 198 positive drug screen results from 121 individuals were registered. Overall, the results did not change between the three phases (before versus during versus after) of the study (χ 2[df = 6] = 1.429, p = 0.964). About Table 2 Patterns of buprenorphine abuse, views about availability and suitable price for BNX (Suboxone) and BUP (Subutex) tablets reported by survey respondents at the needle exchange service in the pre-EMD phase and EMD phase, (EMD = electronic medicine dispenser). Variable BNX user, n (%) BUP user, n (%) Daily buprenorphine user, n (%) BNX most commonly used buprenorphine product, n (%) Availability of BNX is good, n (%) BNX originated from OST, n (%) Mean price (€) of one BNX tablet (8/2 mg) (SD) Mean price (€) of one BUP tablet (8 mg) (SD) Pre-EMD phase (n = 32) 32 15 15 26 (100) (47) (47) (87)b EMD phase (n = 27) 26 18 16 16 (96) (67) (59) (59) p-Valuea 0.458 0.188 0.435 0.033 6 (19) 6 (19) 42.92 (11.67) 8 (30) 5 (19)c 43.34 (7.09) 0.371 1.000 0.943 50.71 (14.45) 55.27 (10.23) 0.110 a Fischer's exact test for categorical variables, Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables. b The responses of two persons are missing. c The response of one person is missing. Please cite this article as: Uosukainen, H., et al., The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone— experience from a medium-sized Finnish City, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003 4 H. Uosukainen et al. / Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment xxx (2013) xxx–xxx 10% of the drug screens (range 8.8–11.4%) were buprenorphinepositive during all the study periods (Fig. 1). Positive drug screens for other opioids (range 20.0–23.8%), benzodiazepines (range 47.9– 53.8%) and other drugs (range 13.8–18.8%) remained stable between the three phases of the study. 4. Discussion To our knowledge this is the first study to have examined whether the comprehensive use of EMDs has a detectable effect on the diversion of BNX. EMDs did not have effect on the buprenorphinerelated health problems treated at the Kuopio University Hospital or on the availability and origin of illegal BNX. However, during the use of EMDs five patients (16%) reported that EMDs had prevented them from diverting BNX and a slightly increasing trend of BUP (single ingredient buprenorphine) instead of BNX abuse was reported by needle exchange service clients. A small number of patients (n = 5, 16%) reported that EMDs had prevented them from diverting their medicines, which represents about half of the proportion of BNX patients that reported diversion (30%) in the study by Larance et al. (2011a). Nevertheless, also treatment practices such as the extent of unsupervised dosing affect the proportion of diversion (Bell, 2010) and therefore, the comparability of these numbers may be limited. Most patients (68%) felt that it was safer to store take-home doses in EMDs compared to paper sachets. Possibly, locked devices were helpful since patients with take-home allowances may have been asked or threatened to pass on their medicines to other users or dealers. Using EMDs may help to reduce this pressure. Treatment staff also appreciated the safety of dosing with EMDs although they were generally pessimistic about the potential of EMDs to prevent diversion. This critical view may have been linked to treatment staff being aware that some patients were tampering with the device. This pitfall was recognized early in the trial. Tampering was performed by forcing the disk with compartments for daily doses into the “open” position by using e.g. a thin pencil. This could not be detected later by visual inspection. However, we believe very few patients did this, because most patients reported that tampering with the device was difficult or impossible. Based on these experiences from the trial, the manufacturer (Addoz Ltd) made technical changes to make the device more tamper-proof. However, the possibility of tampering with the device should be taken into account when using EMDs in clinical practice. Pre-EMD 10.4 % EMD 8.8 % 22.9 % 47.9 % 23.8 % 18.8 % 53.8 % 13.8 % When planning the study, one of our goals was to reduce the availability of illegal buprenorphine and therefore reduce the number of hospital-treated buprenorphine-related health problems. However, this was not observed in the study. The failure to document changes in buprenorphine-positive drug screens may be related to the fact that also patients from outside Kuopio are treated in the hospital emergency department, which may have diluted our results. In addition, our sample size may have been too small to detect changes. BNX was more commonly abused than BUP at both surveys at the needle exchange service. This is not surprising since BNX has been the only licit buprenorphine formulation for OST in Finland since December 2007. However, BNX was the most commonly abused product more often in the pre-EMD phase than in the EMD phase (p = 0.033). The abuse of BUP appeared more common in the EMD phase although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.188). Therefore, there seemed to be a slight shift from BNX to BUP abuse during the study which could support the hypothesis that EMDs may have decreased the availability of BNX from diversion and this could have triggered a shift to other buprenorphine products. Another explanation could be the better availability of BUP in the EMD phase for reasons unrelated to the trial. Since there are many factors influencing illegal drug markets (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2010), these explanations remain speculative. We did not see any change in relation to the availability, price and source of illegal BNX. Possible explanations include tampering with the device, storing of tablets for later diversion and buprenorphine trafficking from other cities or abroad. 4.1. Limitations and strengths This study has certain limitations. The main weakness of EMDs is that they could only detect whether tablets were removed from the device, not how and when the medicine was actually taken. The use of EMDs for a time period of 4 months may have been too short to detect their impact on the street-use of buprenorphine or on the hospitaltreated buprenorphine-related health problems. Buprenorphinepositive drug screens served as a surrogate outcome for buprenorphine-related health problems. The small sample size limited the opportunity for statistical testing and there may not have been enough power to detect changes in outcome measures. Although this study can be regarded as one city's experience with EMDs, its strength lies in comprehensiveness since all eligible local patients were asked to participate and participation rate was high (88%). All BNX patients in the city without exception received their take-home doses in EMDs as part of their routine treatment and, therefore, buprenorphine takehome doses were not granted without EMDs. Several different indicators were used to measure diversion; however, considering the small sample size, qualitative measurements could have been used as well. The number of responses to the surveys at the needle exchange service was quite low (46%, 39%) but rates were satisfactory considering the target population. 4.2. Conclusions and future directions Post-EMD 11.4 % 0% 20.0 % 20 % 50.0 % 40 % Buprenorphine Benzodiazepines 60 % 18.6 % 80 % 100 % Other opioids Others Fig. 1. Proportions of drug screen results positive for buprenorphine, other opioids (methadone, oxycodone, heroin, codeine, morphine), benzodiazepines and others (amphetamine, methamphetamine, cannabis, MDMA) during pre-EMD (n = 48), EMD (n = 80) and post-EMD phases (n = 70), (EMD = electronic medicine dispenser). The use of EMDs provided a feasible method for improving the safe storage of take-home doses of BNX in a naturalistic clinical setting. According to patients' self-report EMDs may prevent some OST patients from diverting their take-home doses. However, there was no clear impact on hospital-treated buprenorphine-related health problems or the availability and price of illegal BNX. Larger studies are needed on the prevention of diversion of OST medicines in different treatment settings. Further refinement of the device may be needed, especially to increase tamper-resistance. Other uses of EMDs could be explored, such as in the treatment of chronic non-malignant pain with opioid-analgesics. Please cite this article as: Uosukainen, H., et al., The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone— experience from a medium-sized Finnish City, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003 H. Uosukainen et al. / Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Acknowledgments The study was supported by grants from the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation (costs related to the use of EMDs and other study expenses) and the Graduate School in Pharmaceutical Research in Finland. The authors would like to thank the treatment staff at treatment units and pharmacies involved in the study, Mr. Antti Törmänen (Addoz Ltd) and PhD Toivo Halonen (Islab Ltd) for technical assistance, and PhD J. Simon Bell and PhD Ewen MacDonald for revising the language. Parts of the manuscript were published as an abstract at the ISAM 2012 Annual Meeting. References Alho, H., Sinclair, D., Vuori, E., & Holopainen, A. (2007). Abuse liability of buprenorphine–naloxone tablets in untreated IV drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, 75–78. Anstice, S., Strike, C. J., & Brands, B. (2009). Supervised methadone consumption: Client issues and stigma. Substance Use & Misuse, 44, 794–808. Arnsten, J. H., Demas, P. A., Farzadegan, H., Grant, R. W., Gourevitch, M. N., Chang, C. J., Buono, D., Eckholdt, H., Howard, A. A., & Schoenbaum, E. E. (2001). Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 33, 1417–1423. Auriacombe, M., Fatseas, M., Dubernet, J., Daulouede, J. P., & Tignol, J. (2004). French field experience with buprenorphine. The American Journal on Addictions, 13, S17–S28. Bell, J. (2010). The global diversion of pharmaceutical drugs: Opiate treatment and the diversion of pharmaceutical opiates: A clinician's perspective. Addiction, 105, 1531–1537. Bell, J., Byron, G., Gibson, A., & Morris, A. (2004). A pilot study of buprenorphine– naloxone combination tablet (Suboxone) in treatment of opioid dependence. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23, 311–317. Bell, J., Shanahan, M., Mutch, C., Rea, F., Ryan, A., Batey, R., Dunlop, A., & Winstock, A. (2007). A randomized trial of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of observed versus unobserved administration of buprenorphine–naloxone for heroin dependence. Addiction, 102, 1899–1907. Bruce, R. D., Govindasamy, S., Sylla, L., Kamarulzaman, A., & Altice, F. L. (2009). Lack of reduction in buprenorphine injection after introduction of co-formulated buprenorphine/naloxone to the Malaysian market. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35, 68–72. Cozzolino, E., Guglielmino, L., Vigezzi, P., Marzorati, P., Silenzio, R., De Chiara, M., Corrado, F., & Cocchi, L. (2006). Buprenorphine treatment: A three-year prospective study in opioid-addicted patients of a public out-patient addiction center in Milan. The American Journal on Addictions, 15, 246–251. Darke, S., Ross, J., & Hall, W. (1996). Prevalence and correlates of the injection of methadone syrup in Sydney, Australia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 43, 191–198. Darke, S., Topp, L., & Ross, J. (2002). The injection of methadone and benzodiazepines among Sydney injecting drug users 1996–2000: 5-Year monitoring of trends from the Illicit Drug Reporting System. Drug and Alcohol Review, 21, 27–32. Degenhardt, L., Larance, B., Mathers, B., Azim, T., Kamarulzaman, A., Mattick, R., Panda, S., Toufik, A., Tyndall, M., Wiessing, L., & Wodak, A. (2008). Benefits and risks of pharmaceutical opioids: Essential treatment and diverted medication. A global review of availability, extra-medical use, injection and the association with HIV. Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/publications/ Benefits_and_risks_of_pharmaceutical_opioids.pdf. Duffy, P., & Baldwin, H. (2012). The nature of methadone diversion in England: A Merseyside case study. Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 3. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2010). Guidelines for collecting data on retail drug prices in Europe: Issues and challenges. EMCDDA Manuals, Lisbon, Portugal. Fiellin, D. A., Moore, B. A., Sullivan, L. E., Becker, W. C., Pantalon, M. V., Chawarski, M. C., Barry, D. T., O'Connor, P. G., & Schottenfeld, R. S. (2008). Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: Results at 2–5 years. The American Journal on Addictions, 17, 116–120. Fiellin, D. A., Pantalon, M. V., Chawarski, M. C., Moore, B. A., Sullivan, L. E., O'Connor, P. G., & Schottenfeld, R. S. (2006). Counseling plus buprenorphine–naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. The New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 365–374. Fishman, S. M., Papazian, J. S., Gonzalez, S., Riches, P. S., & Gilson, A. (2004). Regulating opioid prescribing through prescription monitoring programs: Balancing drug diversion and treatment of pain. Pain Medicine, 5, 309–324. Fishman, S. M., Wilsey, B., Yang, J., Reisfield, G. M., Bandman, T. B., & Borsook, D. (2000). Adherence monitoring and drug surveillance in chronic opioid therapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 20, 293–307. 5 Forsell, M., Virtanen, A., Jääskeläinen, M., Alho, H., & Partanen, A. (2010). Drug Situation in Finland 2010. National report to the EMCDDA by the Finnish National Focal Point. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Report 39/2010, Helsinki, Finland. Fudala, P. J., Bridge, T. P., Herbert, S., Williford, W. O., Chiang, C. N., Jones, K., Collins, J., Raisch, D., Casadonte, P., Goldsmith, R. J., Ling, W., Malkerneker, U., McNicholas, L., Renner, J., Stine, S., Tusel, D., & Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group (2003). Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. The New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 949–958. Fudala, P. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2006). Development of opioid formulations with limited diversion and abuse potential. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83, S40–S47. Gunderson, E. W., Wang, X. Q., Fiellin, D. A., Bryan, B., & Levin, F. R. (2010). Unobserved versus observed office buprenorphine/naloxone induction: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 537–540. Holland, R., Matheson, C., Anthony, G., Roberts, K., Priyardarshi, S., Macrae, A., Whitelaw, E., Appavoo, S., & Bond, C. (2012). A pilot randomised controlled trial of brief versus twice weekly versus standard supervised consumption in patients on opiate maintenance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31, 483–491. Johanson, C. E., Arfken, C. L., di Menza, S., & Schuster, C. R. (2012). Diversion and abuse of buprenorphine: Findings from national surveys of treatment patients and physicians. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 120, 190–195. Johnson, R. E., Jaffe, J. H., & Fudala, P. J. (1992). A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 267, 2750–2755. Kakko, J., Svanborg, K. D., Kreek, M. J., & Heilig, M. (2003). 1-Year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet, 361, 662–668. Larance, B., Degenhardt, L., Lintzeris, N., Bell, J., Winstock, A., Dietze, P., Mattick, R., Ali, R., & Horyniak, D. (2011a). Post-marketing surveillance of buprenorphine– naloxone in Australia: Diversion, injection and adherence with supervised dosing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 265–273. Larance, B., Degenhardt, L., Lintzeris, N., Winstock, A., & Mattick, R. (2011b). Definitions related to the use of pharmaceutical opioids: Extramedical use, diversion, nonadherence and aberrant medication-related behaviours. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30, 236–245. Ling, W., Charuvastra, C., Collins, J. F., Batki, S., Brown, L. S., Jr., Kintaudi, P., Wesson, D. R., McNicholas, L., Tusel, D. J., Malkerneker, U., Renner, J. A., Jr., Santos, E., Casadonte, P., Fye, C., Stine, S., Wang, R. I., & Segal, D. (1998). Buprenorphine maintenance treatment of opiate dependence: A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Addiction, 93, 475–486. Lintzeris, N., Lenne, M., & Ritter, A. (1999). Methadone injecting in Australia: A tale of two cities. Addiction, 94, 1175–1178. Lintzeris, N., Ritter, A., Panjari, M., Clark, N., Kutin, J., & Bammer, G. (2004). Implementing buprenorphine treatment in community settings in Australia: Experiences from the Buprenorphine Implementation Trial. The American Journal on Addictions, 13, S29–S41. Madden, A., Lea, T., Bath, N., & Winstock, A. R. (2008). Satisfaction guaranteed? What clients on methadone and buprenorphine think about their treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27, 671–678. Mammen, K., & Bell, J. (2009). The clinical efficacy and abuse potential of combination buprenorphine–naloxone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 10, 2537–2544. Moore, B. A., Barry, D. T., Sullivan, L. E., O'Connor, P. G., Cutter, C. J., Schottenfeld, R. S., & Fiellin, D. A. (2012). Counseling and directly observed medication for primary care buprenorphine maintenance: A pilot study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6, 205–211. Pradel, V., Frauger, E., Thirion, X., Ronfle, E., Lapierre, V., Masut, A., Coudert, C., Blin, O., & Micallef, J. (2009). Impact of a prescription monitoring program on doctorshopping for high dosage buprenorphine. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 18, 36–43. Ritter, A., & Di Natale, R. (2005). The relationship between take-away methadone policies and methadone diversion. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24, 347–352. Sorensen, J. L., Haug, N. A., Delucchi, K. L., Gruber, V., Kletter, E., Batki, S. L., Tulsky, J. P., Barnett, P., & Hall, S. (2007). Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: A randomized trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, 54–63. Stone, E., & Fletcher, K. (2003). User views on supervised methadone consumption. Addiction Biology, 8, 45–48. Tacke, U., Uosukainen, H., Kananen, M., Kontra, K., & Pentikäinen, H. (2009). A pilot study about the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of electronic compliance monitoring in substitution treatment with buprenorphine–naloxone combination. Journal of Opioid Management, 5, 321–329. Treloar, C., Fraser, S., & Valentine, K. (2007). Valuing methadone takeaway doses: The contribution of service-user perspectives to policy and practice. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 14, 61–74. Winstock, A. R., Lea, T., & Sheridan, J. (2008). Prevalence of diversion and injection of methadone and buprenorphine among clients receiving opioid treatment at community pharmacies in New South Wales, Australia. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 19, 450–458. Please cite this article as: Uosukainen, H., et al., The effect of an electronic medicine dispenser on diversion of buprenorphine-naloxone— experience from a medium-sized Finnish City, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.003