INSURGENCY AND EXCLUSION IN THE MOUNTAINS OF SOUTH

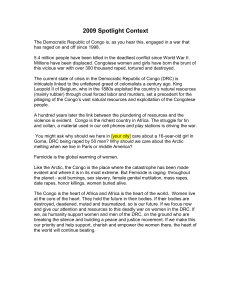

advertisement