creative metropoles

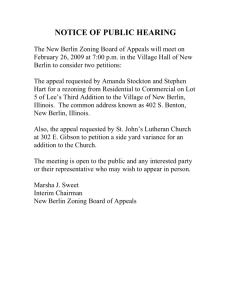

advertisement