full report - National Grid

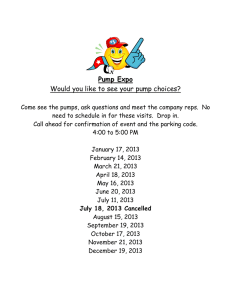

advertisement