Higher Education Reforms and Demand Responsive

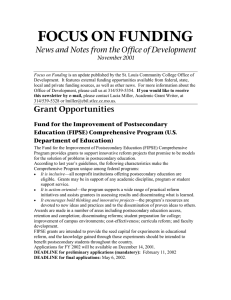

advertisement