American, English and Japanese Warranty Law Compared: Should

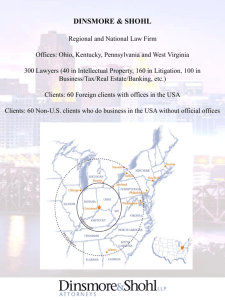

advertisement